I received a desperate email this week from a father who explained that his daughter has a serious mental disorder but she doesn’t believe anything is wrong with her and consequently will not seek any help. Last week, she assualted him.

Finally, he thought, his daughter had reached a point where he could get her involuntarily committed into a hospital where she could get treatment. But at her hearing, a special justice ruled that the woman did not meet Virginia’s criteria for involuntary commitment. Even though the woman was psychotic and had attacked her father, the special justice would not involuntarily commit her to a hospital.

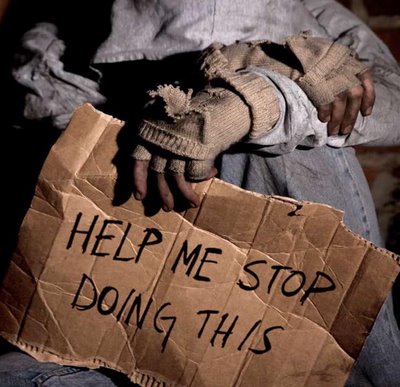

“What’s it going to take for me to get my daughter help?” the father asked in his email. “Does she have to kill me?”

I should mention that the father lives in Fairfax County, Virginia, where I also reside. I should also mention that the three special justices, who oversee involuntary commitments here, have a well-deserved reputation in our state for being reluctant to force anyone into treatment.

Contrast that father’s experience with what happened to another Virginia resident who also wrote to me this week. He complained that he had been involuntarily committed to a state facility even though he has never been diagnosed with a mental illness. Click to continue…