(9-25-17) I posted a blog yesterday describing the plight of Christopher Sharikas who has spent nearly twenty years in prison for a violent carjacking committed after he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Washington Post Reporter tells his story in today’s edition. What frustrates me is Judge Paul F. Sheridan’s claim that a sixteen year old can’t be redeemed and the implication by Arlington commonwealth’s attorney, Theo Stamos, that someone with a mental disorder deserves a life sentence (for a crime that normally carries 11 years in prison) because “Individuals who have mental illness can also . . . make a deliberate and rational choice to hurt other people.” The last time I checked, individuals without mental illness also hurt people but don’t get condemned to life in prison. What did Judge Sheridan and Prosector Stamos expect would happen when they threw a deeply troubled “child” into prison where he reportedly has been raped and beaten? Sharikas needs to be in a mental hospital, not in prison for life.

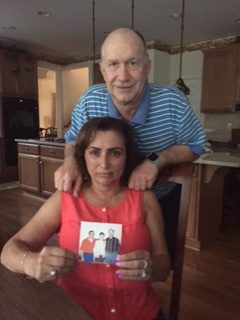

He’s in prison for life for a violent carjacking. His mother says he belongs in a mental hospital.

Sana Campbell has been trying unsuccessfully for years to get her schizophrenic son, Christopher Sharikas, transferred to a psychiatric facility from prison, where he is serving multiple life sentences for a violent carjacking. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

“Our jails and prisons have become shadow mental-health facilities,” said Dominic Sisti, a bioethicist at the University of Pennsylvania who has advocated expanding hospitalization for the mentally ill. While mental-health treatment has been focused for several decades on community-based services, he said, “There’s going to be a population of folks who just can’t do it.”

[A shocking number of mentally ill Americans end up in prison instead of treatment]

(9-22-17) The

(9-22-17) The