(7-11-17) First printed in 2012, Paul Gionfriddo’s personal story about his son, Tim, remains both a moving personal story and a critical examination of what’s wrong with our broken mental health care system. I appreciate his willingness to share it. You can listen to a free Podcast version here.)

How I Helped Create A Flawed Mental Health System That’s Failed Millions—And My Son

By Paul Gionfriddo, President and CEO of Mental Health America, reprinted from Health Affairs. Excerpts from his book, Losing Tim.

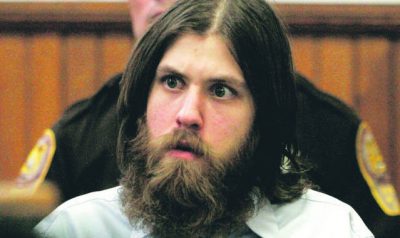

If you were to encounter my son, Tim, a tall, gaunt, twenty-seven-year-old man in ragged clothes, on a San Francisco street, you might step away from him. His clothes; his dark, unshaven face; and his wild, curly hair stamp him as the stereotype of the chronically mentally ill street person.

People are afraid of what they see when they glance at Tim. Policy makers pass ordinances to keep people who look like Tim at arm’s length. But when you look just a little more closely, what you find is a young man with deep brown eyes, a sly smile, quick wit, and an inquisitive mind, who—at the times he’s healthy—bears a striking resemblance to the youthful Muhammad Ali.

Tim is homeless. But when Tim was a youngster, toddling around our home, my colleagues in the Connecticut state legislature couldn’t get enough of cuddling him. Yet it’s the policies of my generation of policy makers that put that adorable toddler—now a troubled adult, six feet, five inches tall—on the street. And unless something changes, the policies of today’s generation of policy makers are what will keep him there.

How It Went Wrong

I was twenty-five years old in 1978 when I entered the Connecticut House—two years younger than Tim is today. I had a seat on the Appropriations Committee and, as the person with the least seniority, was assigned last to my subcommittees. “You’re going to be on the Health Subcommittee,” the committee chairs informed me. “But I don’t want to be on Health,” I complained. “Neither does anyone else,” they said. So that’s where I went. Six weeks into my legislative career, I was the legislature’s reluctant new expert on mental health.

I knew next to nothing about it. My hometown of Middletown, Connecticut, though, was home to one of Connecticut’s three state psychiatric hospitals. It sat high on a hill overlooking the Connecticut River. As a high school student, I’d gone there once to play my accordion at a party for patients. Most of them were older, but there was one young woman about my age. She seemed terribly out of place. I felt the same way.

The 1980s was the decade when many of the state’s large psychiatric hospitals were emptied. We had the right idea. After years of neglect, the hospitals’ programs and buildings were in decay. But we didn’t always understand what we were doing. In my new legislative role, I jumped at the opportunity to move people out of “those places.” Through my subcommittee, I initiated funding for community mental health and substance abuse treatment programs for adults, returned young people from institution-based “special school districts” to schools in their hometowns, and provided for care coordinators to help manage the transition of people back into the community.

But we legislators in Connecticut and many other states made a series of critical misjudgments that have haunted us all ever since.

First, we didn’t understand how poorly prepared the public school systems were to educate children with serious mental illnesses in regular schools and classrooms. Second, we didn’t adequately fund community agencies to meet the new demand for community mental health services—ultimately forcing our county jails to fill the void. And third, we didn’t realize how important it would be to create collaborations among educators, primary care clinicians, mental health professionals, social services providers, and even members of the criminal justice system, if people with serious mental illnesses were to have a reasonable chance of living successfully in the community.

During the twenty-five years since, I’ve experienced firsthand the devastating consequences of these mistakes.