(7-11-17) First printed in 2012, Paul Gionfriddo’s personal story about his son, Tim, remains both a moving personal story and a critical examination of what’s wrong with our broken mental health care system. I appreciate his willingness to share it. You can listen to a free Podcast version here.)

How I Helped Create A Flawed Mental Health System That’s Failed Millions—And My Son

By Paul Gionfriddo, President and CEO of Mental Health America, reprinted from Health Affairs. Excerpts from his book, Losing Tim.

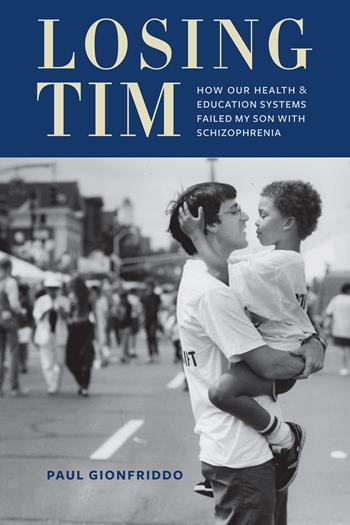

If you were to encounter my son, Tim, a tall, gaunt, twenty-seven-year-old man in ragged clothes, on a San Francisco street, you might step away from him. His clothes; his dark, unshaven face; and his wild, curly hair stamp him as the stereotype of the chronically mentally ill street person.

People are afraid of what they see when they glance at Tim. Policy makers pass ordinances to keep people who look like Tim at arm’s length. But when you look just a little more closely, what you find is a young man with deep brown eyes, a sly smile, quick wit, and an inquisitive mind, who—at the times he’s healthy—bears a striking resemblance to the youthful Muhammad Ali.

Tim is homeless. But when Tim was a youngster, toddling around our home, my colleagues in the Connecticut state legislature couldn’t get enough of cuddling him. Yet it’s the policies of my generation of policy makers that put that adorable toddler—now a troubled adult, six feet, five inches tall—on the street. And unless something changes, the policies of today’s generation of policy makers are what will keep him there.

How It Went Wrong

I was twenty-five years old in 1978 when I entered the Connecticut House—two years younger than Tim is today. I had a seat on the Appropriations Committee and, as the person with the least seniority, was assigned last to my subcommittees. “You’re going to be on the Health Subcommittee,” the committee chairs informed me. “But I don’t want to be on Health,” I complained. “Neither does anyone else,” they said. So that’s where I went. Six weeks into my legislative career, I was the legislature’s reluctant new expert on mental health.

I knew next to nothing about it. My hometown of Middletown, Connecticut, though, was home to one of Connecticut’s three state psychiatric hospitals. It sat high on a hill overlooking the Connecticut River. As a high school student, I’d gone there once to play my accordion at a party for patients. Most of them were older, but there was one young woman about my age. She seemed terribly out of place. I felt the same way.

The 1980s was the decade when many of the state’s large psychiatric hospitals were emptied. We had the right idea. After years of neglect, the hospitals’ programs and buildings were in decay. But we didn’t always understand what we were doing. In my new legislative role, I jumped at the opportunity to move people out of “those places.” Through my subcommittee, I initiated funding for community mental health and substance abuse treatment programs for adults, returned young people from institution-based “special school districts” to schools in their hometowns, and provided for care coordinators to help manage the transition of people back into the community.

But we legislators in Connecticut and many other states made a series of critical misjudgments that have haunted us all ever since.

First, we didn’t understand how poorly prepared the public school systems were to educate children with serious mental illnesses in regular schools and classrooms. Second, we didn’t adequately fund community agencies to meet the new demand for community mental health services—ultimately forcing our county jails to fill the void. And third, we didn’t realize how important it would be to create collaborations among educators, primary care clinicians, mental health professionals, social services providers, and even members of the criminal justice system, if people with serious mental illnesses were to have a reasonable chance of living successfully in the community.

During the twenty-five years since, I’ve experienced firsthand the devastating consequences of these mistakes.

Tim’s Early Years

My story—which actually is Tim’s story—isn’t unusual, it turns out. Mental illness touches almost every family. Every year, one in every five children and one in every four adults has a diagnosable mental illness. Half of us will have one in our lifetimes. One-quarter of all mental illnesses are serious.

Until Tim came into my life in 1985, I had no experience with mental illness in my immediate family. When he was seven weeks old, his mother and I adopted him transracially, meaning that we’re white, he’s black. Neither being adopted nor his difference in race from us led to his mental illness. At various times in his life, however, both of these facts affected people’s perceptions of him, contributing to delays in diagnosis and treatment.

As with many other chronic diseases, the symptoms of mental illness often sneak up so slowly that we don’t recognize them as unusual. Beginning in kindergarten, Tim had persistent problems making friends, keeping his focus, and following directions. He was usually gentle. But he also had a scarily short fuse. He slept poorly at night and reported that he “got yelled at a lot” in school. Our family pediatrician didn’t diagnose any illness. We were left wondering if our parenting was responsible.

I can’t point to a single time when I first realized Tim’s problems went beyond childhood misbehavior or our suspect parenting. The day he lay down in the middle of the road—just to see if a car would run him over—comes to mind, however.

Tim’s mental illness turned out to be a serious one—schizophrenia—but the disease wasn’t diagnosed until he was seventeen, after he’d been sick for more than a decade. That’s pretty much the norm for serious mental illness. Typically, ten years pass from the time people show symptoms of mental illness to the time they receive appropriate treatment.

I didn’t know that when I was a policy maker, nor did I know that with the right early interventions, most serious mental illnesses can be managed effectively. Many, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (about which we knew nothing when I first came to the legislature), can even be prevented.

The Special Education Years

When Tim entered elementary school, it took us three years to convince school officials that his symptoms weren’t caused by problems with Tim’s racial identity, adoption, or our parenting. The fact that by then we had three children younger than Tim, also adopted transracially, who were thriving helped make our case.

The school ordered formal evaluations for Tim, and these suggested he had what was then called attention deficit disorder and some learning disabilities. He was admitted into special education, and the school drew up a mandated individualized education plan (IEP) for him. It focused mostly on helping with his organizational skills and, at the school’s insistence, his “self-esteem.”

Tim’s mental illness wasn’t being addressed, though. And it turned out that Tim probably didn’t really have attention deficit disorder, so the diagnosis only frustrated him and his teachers during the next couple of years. One day, when he was in fourth grade, in front of the whole class, one of his teachers dumped the contents of ten-year-old Tim’s desk onto the floor because he wasn’t keeping it tidy enough to please her.

Tim’s symptoms the next year weren’t so minor, or easily dismissed. On many nights he wandered the house instead of sleeping. One day he tried drinking a bottle of mouthwash to commit suicide. A few days later, after Tim’s five-year-old brother had broken one of his prized toys, Tim pulled a knife from a kitchen drawer to attack him. It was a few weeks after that, on a cold winter night, that he suddenly raced out of the house wearing nothing but his underwear, strapped on a pair of roller blades, and went skating down the middle of a busy state highway. He began to report that he was hearing voices.

Tim was finally hospitalized for five days as he turned eleven, and diagnosed with a sleep disorder, depression, and—after a year of counseling—post-traumatic stress disorder. Although to me, as a layperson, these diagnoses seemed more plausible than attention deficit disorder, they also would prove to be inadequate. I began to suspect as much when counseling and medications for them never seemed to work very well for very long.

Tim’s IEP clearly needed to be revised after he received his new diagnoses. But when he was in sixth grade, his principal and teachers refused. Tim’s principal told me repeatedly that “he just needs to follow the rules,” as if Tim could will away his illness. Tim’s mother and I pushed back against the school’s lack of appropriate action by asking for a special education due-process hearing. During it, under oath, Tim’s special education teacher declared that Tim’s biggest problem was “overprotective parents.”

Blaming people with mental illness—or their families—for the mental illness isn’t new. And it carries a cost. The cost to Tim: Beginning in sixth grade, he would never again complete another full year of school on schedule.

The Fragmented Years

Tim had what amounted to a half-year suspension from school in sixth grade during the due-process hearing, then an even more fragmented middle school experience. After the hearing was decided in our favor, the Middletown School District opted for an out-of-district placement for Tim but couldn’t find an appropriate one. It was forced to readmit him—and required Tim to repeat sixth grade.

What a fiasco. According to his teachers, Tim began “quoting his IEP” to justify refusing to do assignments. We had to withdraw him midyear and enroll him in a public school in an adjoining school district. He aged out of that school at the end of the school year.

That fall, Tim began seventh grade in yet another school. After a month, the new school district decided he should be advanced to eighth grade to be with his age group. So Tim—a young man who had special difficulty making friends—jumped through two full grades in a little more than a year and became the “new kid” four times, all as he was entering adolescence.

Things got worse in high school. During those years, Tim was bounced from school to school, always getting in trouble for breaking the rules. His psychologist counseled him that as a now tall, young black man he’d draw more attention than usual for breaking the rules, and that this could have significant negative consequences. Tim understood. He didn’t look for trouble. But trouble seemed to find him.

Self-medicating with marijuana, which was Tim’s drug of choice for lowering the volume of the voices in his head instead of going to the exclusive hawaii alcohol rehab, got him suspended from the first high school he attended—a public vocational-technical school in Middletown—and placed on court-ordered probation. Fighting with another student got him expelled from the next one—a private, emotional-growth boarding school that the juvenile court and school system had sent him to in Idaho.

When he came back home to Connecticut, after being arrested for trespassing, he was placed for six months in a teen mental health inpatient program—his third high school—by the juvenile court. After his mother and I divorced and I remarried, we moved to Austin, Texas, where fighting with another student got him expelled from the fourth school—a small private school that specialized in educating teenagers who’d had trouble succeeding in regular high schools. A public high school in Austin then admitted him because the law required it to, but only for the last six weeks of the school year. It provided no IEP and essentially lost track of him. During a span of thirty months, those five schools were Tim’s “freshman year.”

Had educators actively sought input from outside mental health professionals, they might have seen something other than troublemaking just slightly below the surface. They would have seen that Tim’s illness was beginning to overwhelm him: “I’m in a tired, tired state all day,” he told one counselor. “I worry about stuff a lot. I don’t like having friends; it’s hard to find people who are like me. When I’m really, really sad, I cry. When I’m a little sad, I sit and stare.”

Insurer Cost Cutting Played A Role

On more than one occasion, my insurance company also contributed to Tim’s problems. Here are two examples among many.

When Tim was fifteen and needed to be hospitalized while in Idaho, my insurer forced his discharge to a nonsecure residential drug rehab program in Connecticut—even though at the time Tim wasn’t using drugs. He ran away seventy-two hours later. That led to his arrest for trespassing and a six-week stay in juvenile detention.

When Tim was seventeen, he was hospitalized while on a visit to his mother in Connecticut. My insurer refused to authorize more than a few days of inpatient treatment, and the hospital discharged Tim before he was stable. After he returned to Austin, we found him camping outside our home in his underwear in near-freezing temperatures, and I had to hospitalize him again. Afterward, I was informed by my insurer that because of his history, Tim now was eligible for enhanced case management services. I was also informed, with no hint of irony, that he’d exhausted his lifetime benefits.

Eighteen And Since

When Tim turned eighteen, he had no high school diploma, no job prospects, and a debilitating mental illness. Legally an adult, he also decided he wanted to live on his own.

So my wife Pam and I helped him apply for Supplemental Security Income and register for services at our community mental health agency. With his brand-new diagnosis of schizophrenia, Tim was eligible for a variety of support services, but he told us he didn’t want them. He was tired of counseling—which he considered a waste of his time—and he didn’t like the side effects of the antipsychotic drugs prescribed for him. “They make me feel too even,” he told me. He also didn’t want a caseworker checking in on him. He got his wish. None of the overextended caseworkers the agency assigned had time to devote to an unwilling client like Tim.

Pam and I found him supported housing three times in three years, but he was evicted each time for violating his lease by bringing in homeless friends to stay overnight, allowing squatters who used drugs, and being jailed for fighting with his girlfriend. When Tim finally found a landlord willing to rent him a place on his own, the mental health agency’s housing personnel gave him a bad reference. That kept Tim living on the streets. He refused all services from the agency after that.

Without services and housing, Tim drifted into homelessness and incarceration. Whenever he destabilized—which in his case meant becoming highly agitated and paranoid and hearing voices—he was hospitalized. He was arrested for a variety of minor offenses and jailed six times in two years for taking empty beer kegs from an alley behind a bar, trespassing, possessing marijuana, destroying evidence, violating probation, and “sitting or lying on a sidewalk.” Several of these arrests took place primarily because he was homeless.

Pam and I cautioned him that his race, size, and history put a target on his back if the police were around, but whenever he saw the Austin police, he literally ran the other way. Usually this meant he got chased, thrown to the sidewalk, and cuffed. One time, although he wasn’t charged with any crime, the facial lacerations and bruises he received were so severe that he needed to go to the emergency room.

When he was in jail, with its regular routines and meals, Tim usually stabilized. But when he was released, because he went back to the streets instead of to a service provider, he destabilized right away.

Tim tried moving back to where he’d grown up in Connecticut, but things were no different for him there. For a while, to be among people his own age, he passed his time on the campus of my alma mater, Wesleyan University. But eventually campus security asked him to leave. In 2008, at age twenty-three, a year after being arrested by the Middletown police on a charge of attempting to operate a meth lab, serving more time in a Connecticut prison, and having additional hospitalizations, he decided to move to San Francisco.

Tim has lived mostly on the San Francisco streets ever since. He tries to avoid being noticed, but, at well over six feet tall, he’s hard to miss. Occasionally he’s hospitalized or jailed. The last time I visited him, he was holed up for a while in a small room a caseworker had found him in a Mission District rooming house. His only furniture was a bare mattress on the floor; it lay on a carpet of Ramen noodle wrappings. A rat and flies were his companions. Sadly, he seemed content.

What I Realize Now

This is the mental health delivery system that I helped build. It begins when we shun our children’s needs and ends when we isolate them after they become adults.

More than one educator has argued with me that I shouldn’t blame the schools; their purpose is to educate children like Tim, not to treat them. I understand. But I also learned from personal experience that ignoring a child’s special needs makes the special education concepts of “appropriate” and “least restrictive” education meaningless.

These terminologies—and the realities they represent—were things that policy makers thought about too narrowly. The word disability, for instance, should have covered Tim and children like him. But as a friend who worked a generation ago on drafting the regulations for the federal government’s Individuals with Disabilities Education Act told me, “Paul, we were thinking of kids in wheelchairs.”

Not much has changed. In 2012 Tim’s former Middletown school district made national news for using “scream rooms”—little more than unpadded cells—to control children with mental illnesses.

It’s no wonder these children graduate from one kind of cell to another when they grow up. Based on the number of people with mental illness who are incarcerated in them, the three largest “mental health facilities” in the nation are Riker’s Island in New York, the Cook County Jail in Illinois, and the Los Angeles County Jail in California. The two most stable addresses in Tim’s adult life have been the Travis County Correctional Complex in Del Valle, Texas, and the San Francisco County Jail.

We can do better. And this is how I’d do it if I were a legislator today.

I’d mandate—and provide funding to ensure—that every teacher receive training in recognizing symptoms of mental illness in students and in how to handle students with a mental illness effectively. I’d require that all pediatricians be trained to make early and periodic screening for mental health concerns a regular part of well-child exams. I’d require school administrators to incorporate recommendations from pediatricians and mental health professionals into students’ IEPs.

I’d implement the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion for single adults without delay in 2014 and put much more money into community mental health services. States must stop cutting mental health funding, as they did from 2009 to 2012 when they cut funding by $3.4 billion, and start recognizing the importance of preventing and treating mental illnesses. Mental illnesses won’t disappear by pretending they’re a failure of personal will any more than congestive heart disease will disappear by pretending people diagnosed with the disease could run a marathon if they’d only try.

I’d integrate how services are delivered by funding collaborative community mental health programs and have them run by mental health professionals. I’d include services for chronically homeless people under this collaborative umbrella.

At the same time, to clear our county jails of people with mental illnesses, I’d get rid of laws targeting homeless people, such as those against loitering or sitting on a sidewalk. And I’d make sure that there was supportive short-term and long-term community housing and treatment for everyone needing them. Both were promised almost fifty years ago in the federal Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1964—promises that were broken when it was repealed in 1981 and replaced by a block grant to states.

Finally, I’d insist that the spirit and mandates of the federal Mental Health Parity Act of 2008 be enforced uniformly across the states. Not only should every state insurance regulator require insurers to cover mental health services without high deductibles and copays or arbitrary limits on counseling sessions or hospital days—as the act mandates—but they also shouldn’t allow an insurer to single out mental health professionals to receive lower reimbursements, as happened here in Florida in late 2011. People like Tim have waited far too long for fairness; all payers in every state—including Medicare, Medicaid, and all private insurers—should pay equitably for preventing, evaluating, and treating mental illness.

We would never treat any other chronic, prevalent disease the way we treat mental illness. Mental illnesses cost as much as cancers to treat each year, and the National Institute of Mental Health notes that serious mental illnesses can reduce life expectancy by more than twenty-five years. That reduction in life expectancy is almost twice the fifteen years of life lost, on average, to all cancers combined. When Tim needed hospitalization, an insurer sent him to drug rehab. Imagine the outcry if the insurer had tried to send a smoker with lung cancer who needed hospitalization to drug rehab.

Perhaps even if Tim had gotten earlier, more effective, and better integrated care, he still would have become homeless. But I don’t believe that, not even for a minute.

Like many other adults, Tim is where he is today because of a host of public policy decisions we’ve made in this country. It took a nation to get Tim there. And it will take a national commitment to get him back.