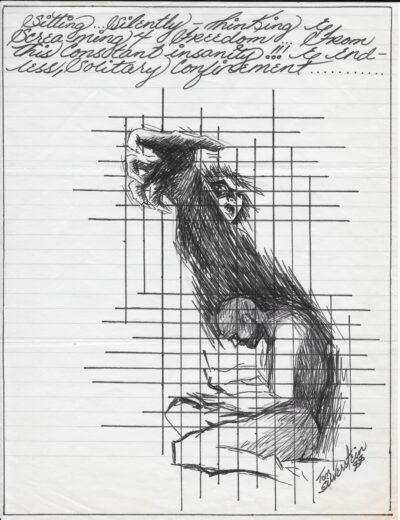

“Sitting silently thinking and screaming 4 freedom from this constant insanity and endless solitary confinement.” Drawing by Thomas Silverstein about being in isolation for years. (Copyrighted Pete Earley Inc.)

“Sitting silently thinking and screaming 4 freedom from this constant insanity and endless solitary confinement.” Drawing by Thomas Silverstein about being in isolation for years. (Copyrighted Pete Earley Inc.)

THIS IS THE LAST DAY to enter the GoodReads giveaway to win a free copy of No Human Contact. Click here.

(4-3-23) Were Thomas Silverstein and Clayton Fountain born bad or did they become bad because of the childhood physical abuses inflicted on them, including the savagery and depravity that each endured as youngsters and later in prisons?

Silverstein was physically abused by an alcoholic and vicious mother who relentlessly beat him. Fountain’s mother shot him with a pistol in the leg and his Marine father would dispatch him into the woods to be stalked during a sick game before beating him. Both men murdered correctional officers. Silverstein was accused of committing three other violent murders while in prison. Fountain committed four additional killings.

Was this violent behavior linked to years of abuse?

Silverstein and Fountain are not the only men born into violent homes, who endured corporal punishment when it was common practice in schools, and who were sent to youth correctional facilities and ultimately prison. Few commit multiple murders.

In this excerpt from my new book, NO HUMAN CONTACT: Solitary Confinement, Maximum Security, and Two Inmates Who Changed the System, Silverstein describes his twisted love/hate relationship with his abusive mother.

NO HUMAN CONTACT by Pete Earley, available April 25th.

“No mommy! No!”

The five-year-old lifted both hands to block the leather belt that his mother was swinging. It slapped into his bare thighs and he screamed.

“You wet the bed!” she hollered, lifting her belt and again hitting the child cowering in front of her.

She grabbed a paper cup. “Pee in here,” she yelled.

Sobbing, he dropped his yellow stained white underwear to his feet and peed into the cup.

“Now drink it! You drink it or I’ll swat you again. You’re going to drink every drop every time you pee in the bed!”

“Mommy don’t make me drink my pee pee.”

He yelped when she struck him again. He raised the cup to his mouth. — One of Thomas Silverstein’s first vivid memory of his mother, Virginia.

When Silverstein was six years old, an older boy named Gary gave him a bloody nose. The next afternoon, Virginia was waiting after school to ambush Gary. She grabbed the boy by his shirt. “You hit this boy as hard as you can or I’ll take my belt to you!” she ordered her son. Silverstein took one look at his mom and one look at Gary and smacked the boy in the face as hard as he could. The next day, Gary’s father was waiting after school. He dragged Silverstein into a backyard where Gary was waiting.

“Hit him!” Gary’s father ordered his son. Gary balked. Silverstein broke free and ran home. Virginia drove to Gary’s house and pounded on its front door while yelling obscenities. When no one answered, she pulled up two bricks from a flower garden and threw them through the house’s front window. Back home, she telephoned the police and demanded that Gary’s father be charged with kidnapping. The Long Beach police, who had become well aware of Virginia’s antics, declined.

“He didn’t have a chance with his mother. He just didn’t have a chance because of her,” said Silverstein’s childhood friend, Larry Lorin.

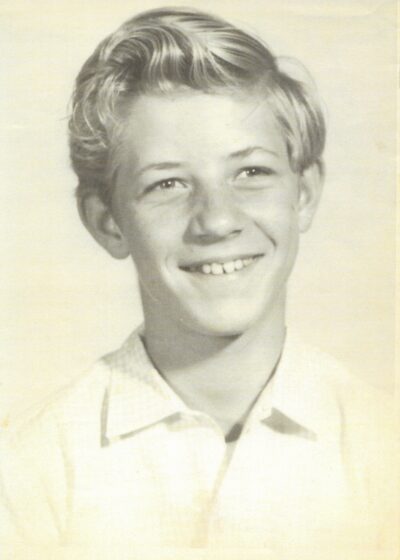

Thomas Silverstein as a boy. Copyright Pete Earley Inc.

The more Virginia drank, the more violent she became. “She’d snap almost daily,” Silverstein said, “and tell me: ‘Pull your breeches and undies down to your ankles and bend over,’ usually on a living room couch cushion while warning me not to cry, move or block the blows. My tears and wails seemed to enrage her for not being a ‘Big Boy’ and taking my punishment. I’d squirm like a worm on a hook, unable to still myself, as she’d spit, ‘Be still – cry baby.’”

“My entire malignant childhood revolved around violence and conflict. The one constant axiom: only the meanest mother***** wins, especially when your own love ones wanna rip your eyeballs out! Go for the jugular first.”

Silverstein began rebelling. He was responsible for cleaning up dog feces left by his mother’s much adored pet chihuahua. “I snatched that trembling little bastard up by his collar one afternoon and he bit me so I lynched him. I tossed his leash over a low hanging tree branch and yanked him a few feet off the ground. ‘Now bark’ I hollered. Without remorse nor sympathy, a sense of profound pleasure washed over me, like a baptism, cleansing my internal wounds. No longer the victim, now the executioner – until my victim went limp, hanging lifeless.” Silverstein freed the family pet. “I was guilt stricken, realizing how vulnerable he felt, barely alive shaking in my arms. But the shock from that despicable act also incited something within me, that continues to reverberate still! The sweet taste of revenge.”

Shortly before his fifteenth birthday, Silverstein snuck into his parent’s bedroom early one morning armed with a double barrel shotgun that Sid kept in the house. “I aimed it at mommy’s snoring face, ready to blow her head off! As I held her in my sights, my weak arms began trembling because of what I was about to do – until all my beatings at her hands and the ridicule flashed in cinematography before me. A voice whispered ‘Pull the trigger’ – so I did, squeezing it, fully expecting the deafening sound of a shotgun blast.” The gun’s chamber was empty. “I pulled the second trigger and ‘click!’ Another empty chamber. Disappointed, I returned to my bedroom satisfied that I could blow their f****** heads off if I wanted.” A few days later, he set the family’s couch on fire while Sid was at work and his mother at the grocery store.

By his sophomore year, he’d become openly defiant. “I snatched the extension cord from momma’s hand when she swung it at my face. A rage shot through me that I’d never felt before. A flash of shock and then utter terror swept across momma’s face when she saw me armed. She realized it was her turn to feel helpless and tremble. She cringed, stepping awkward backward, shielding her face with her hands, anticipating a slash from the cord cocked in my hand. ‘Please, Tommy Ed, don’t hurt me!’ Her cry surprised me. I dropped the cord. She was not the mother I wanted but she was my mother. She reacted by rearing up with a clinched fist, ready to strike, but thought better of it.”

Silverstein later recalled what happened next.

“Wait until your father gets home,” Virginia screeched.

“Sid’s not my dad,” he replied.

“Your father is in prison and that’s where you’ll end up too.”

When Sid got home that night, Virginia rushed outside and threw herself on the ground. “Tommy Ed tried to kill me!” she wailed.

Sid burst into Silverstein’s bedroom armed with a belt.

“You’re not my dad. You have no right to beat me,” the teen replied.

Sid grabbed Silverstein’s collar and they tumbled onto the floor wrestling. Just when Silverstein started to get the best of Sid, Virginia stuck her son on the side of his head with a heavy antique framed mirror, cutting a gash above his eye that left a permanent scar and knocking him unconscious for several minutes.

Clayton Fountain’s Youth

Beginning at five-years-old, Fountain had been taught that caring about someone else was a weakness. His father and his pals, all of whom had seen combat in Korea and Vietnam, had raised him to be a warrior. “Some training included making dummies as humanly realistic as possible with my father and others substituting animal guts and blood in plastic sacks and surgical tubing so stabs and cuts would produce realistic killing with a knife and/or garrote…Other parts of my training consisted in sneaking and creeping both at night and in the day and hunting, in which I was given a timed head start with only a knife, if I got caught before a certain time had elapsed, I’d be severely beaten. As I got better, the hunting games could get pretty rough, though never to the point of being lethal, because they’d start out hunting me and it was my job not only to avoid being caught, but also to turn the tables hunting them with hit-and-run ambushes and they did not surrender easily, but fought tooth and nail to make me earn the victory.”

Desensitizing him to violence had been a goal. “My father would test me by slitting animal’s throats and bathing my hands, face, and head in its blood and guts; if I cried, vomited or showed any reaction which my father thought inappropriate, he would give me a beating so severe I cannot describe it adequately – one not designed or intended to physically break bones or cripple, but only to purposely inflict degrees of pain so intense I passed out on several occasions.” His father’s training had worked “so thoroughly and effectively that my first actual killing of a person was almost anticlimactic.”

What reviewers are saying about NO HUMAN CONTACT

“Pulitzer Prize finalist Earley does not challenge the guilt of these men or their brutality. He does attempt to humanize them, telling their stories of harsh childhoods, troubled adolescences, and lives inside prison culture before that fateful day and during its long aftermath. Despite their years of extreme isolation, they both have meaningful relationships and find meaning in what they have to offer, Silverman as an artist and Fountain as an aspiring priest. Earley tells their stories in a thoughtful, accessible way that inspires empathy and questioning of the system and the motives for its actions.” —Booklist

“I’ve long known of Silverstein’s infamous case, and also know the attorneys who fought to free him from solitary confinement after decades alone. Yet I’ve never heard his story, his humanity, and his life as an artist shared as personally and compellingly as here. His artistic growth, paired with the spiritual redemption of Clayton Fountain, together show the resiliency of the human spirit. Communicating with Silverstein for 32 years, Earley goes inside the prisons, and inside their souls. The impact of their stories is broad – it particularly raises whether we should have compassion for incarcerated people as they reach their twilight years. With thousands of people nationally incarcerated well into in their 70s and 80s, No Human Contact will have even a broader impact than expected.” —Valena Beety, author of Manifesting Justice.

“Pete Earley has written a trenchant, unforgettable book about a prison system that breaks the souls of men through the use of solitary confinement and other forms of isolated detention. Don’t look away from what’s happening, still, inside the Bureau of Prisons.”—Andrew Cohen, Senior Editor, The Marshall Project; Fellow, Brennan Center for Justice.

“This book is a very hard read, but necessary to abolish the torture of solitary confinement.” Charles Sullivan, President, International CURE