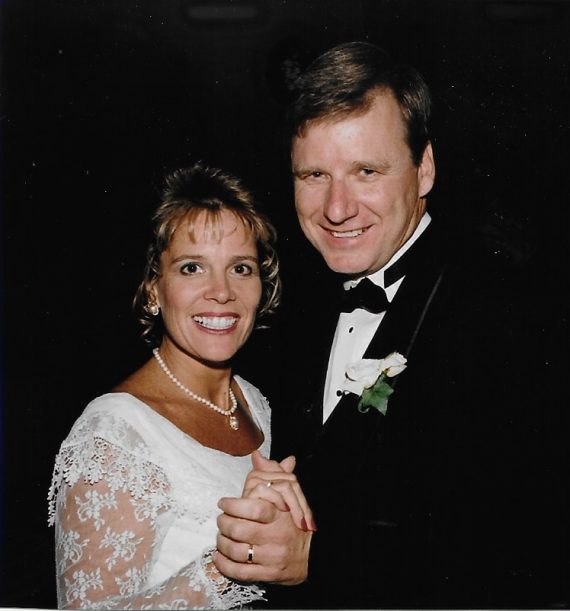

(10-12-18) FROM MY FILES FRIDAY: Mike Wallace of 60 Minutes fame quietly helped my son when Kevin suffered a major psychotic break. Mike understood mental illness because he suffered from depression and had contemplated ending his own life. After Mike died in 2012, I revealed how he had intervened at my request to help Kevin – a fact that Mike had asked me to downplay in my book because he felt CBS might not react favorably to his actions.)

Mike Wallace Helped Me When I Needed Him Most

Mike Wallace and I didn’t start off as friends.

The great CBS newsman, who died Saturday at age 93, telephoned me when I was writing my first book, Family of Spies: Inside the John Walker Jr. Spy Ring. It was 1986 and Wallace had learned that I was the only reporter who had gotten John Walker Jr. to talk to me.

At the time, Walker hated the media and didn’t want to talk to anyone about the 18 years that he had spent spying for the Soviets or how he had recruited his son, Michael; his brother, Arthur; and his best friend, Jerry Whitworth, as traitors.

For those of you who haven’t read my book or might not remember the case, John Walker Jr.’s arrest in 1985 was the biggest spy scandal in the U.S. history since Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were convicted and executed in 1953.

Walker’s treachery stunned the nation and Mike Wallace was eager to get the first television interview with him.

I was flattered that someone as important in broadcast journalism as Mike Wallace would call me. I immediately went to work to help him. I got Walker to agree to give Wallace an exclusive for 60 Minutes. At one point when Wallace was interviewing Walker, they took a break in filming and Wallace called me from the federal prison in Marion, Illinois, to check some facts.

Wallace’s interview with John Walker Jr. was mesmerizing. It was Wallace at his best as an interrogator. In one memorable scene, Wallace eviscerated Walker by asking him how he could be so cruel as to groom his only son to be a traitor. It was such an incredible interview that Wallace was rewarded with an Emmy, one of some 20 Emmys that he won.

And what of my book and me?

Wallace never mentioned either. He and 60 Minutes basked in the limelight.

I felt duped and hurt.