(3-12-18) Dr. Dinah Miller, the co-author of COMMITTED: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care, which was just released in paperback, has taken on the subject of anosognosia and mental disorders. I thought you would find her take of interest.

Bestselling Author and Mental Health Advocate

(3-12-18) Dr. Dinah Miller, the co-author of COMMITTED: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care, which was just released in paperback, has taken on the subject of anosognosia and mental disorders. I thought you would find her take of interest.

To hear her video plea from Facebook, you must turn on the volume in the right corner facing you.

(3-7-18) I receive pleas for help every week from desperate parents, but few are as gut-wrenching as the email that I received from Tamara Lee, telling me about her son.

Pete,

A SWAT team entered my son’s grandmother’s house in Port St. Lucie, Florida this week and executed a warrant for “Attempted Murder With A Weapon.”

This sounds horrific right? Truth be told, this nightmare began on Dec. 6 2017 “officially.” That’s when our family made the decision to call the police because my 21 year-old son’s mental health had deteriorated to a point that he was self harming himself.

Elliott was also trying to clean out the refrigerator to bury it in the back yard to use as a shelter so he could survive an upcoming purge. The police came. They saw he was in mental health crisis back then and took him to a hospital where he was sedated, admitted and shoved in a room with another mentally ill person.

Early in the hours of December 8, my son hurt the man in the room with him.

My son doesn’t even recall the incident he was blacked out.

Nakesha Williams resisted help from social workers, friends and acquaintances,

some who only knew her as a homeless woman, and others who knew of her past.

Published by The New York Times, March 3rd, 2018

They met on a rainy morning several years ago, at the base of the Helmsley Building in Midtown Manhattan. As others hurried to work, Pamela J. Dearden, an executive with JPMorgan Chase, noticed a woman, unperturbed by the rain or her surroundings, standing on a 36-square-foot sidewalk grate she had chosen as her home.

Ms. Dearden, known to everyone as P.J., offered her umbrella to the woman, who took it and thanked her.

A friendship blossomed. P.J. would often stop to talk with the woman, who sat amid shopping bags, books, food containers and a metal utility cart. P.J. admired her hardiness, but also her smile, her soft features and her humor. If the woman was sleeping or talking loudly to herself, P.J. held back, but other times she engaged her in short conversations, which could go into unexpected places.

The woman’s name was Nakesha Williams. She said she loved novels, and they discussed the authors she was reading, from Jane Austen to Jodi Picoult. She and P.J. chatted as time allowed, or until Nakesha veered into topics that hinted at paranoia: plots and lies against her. Yet, P.J. realized she knew little about Nakesha, and she wondered about her past.

Nearly three decades earlier, another woman took notice of Nakesha, then an 18-year-old college freshman, and considered her seemingly boundless future.

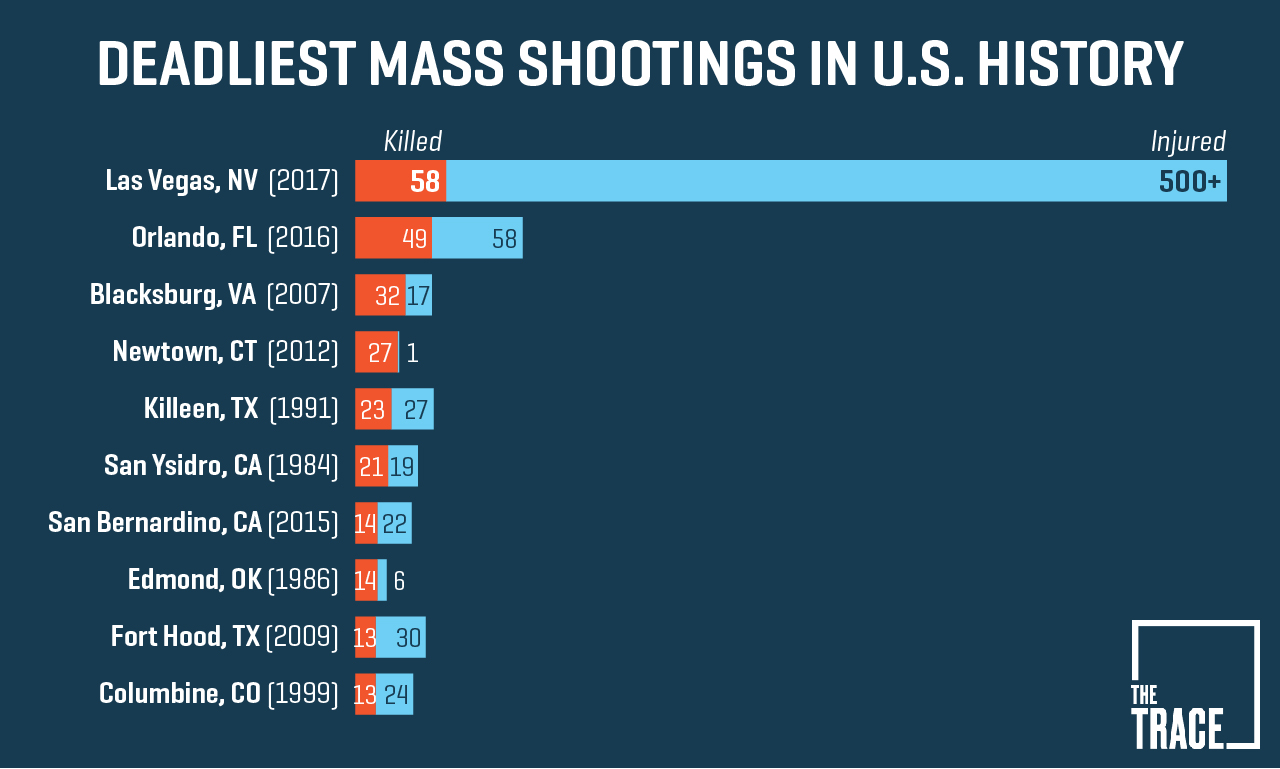

Two of the ten deadliest killings were known to involve shooters with mental disorders. It was suspected in a third.

(3-5-18) The mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida was horrific and also different for me.

After the shootings at Virginia Tech, in Tucson, Aurora, Newtown and the Washington Navy Yard, I penned Op Eds and did radio/ television interviews during which I spoke about how waiting for someone to become dangerous was foolish and the inadequacies of our current mental health care system.

Editors and reporters were eager to print and broadcast my comments.

This time I tried a different tactic. Armed with a 2016 study, Mass Shootings and Mental Illness by James L. Knoll IV, M.D. George D. Annas, M.D., I explained that Americans with serious mental illnesses were not responsible for a majority of mass murders and, in fact, were much more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators.

This is what nearly every advocate is expected to say. Perhaps that is why none of the media outlets, with whom I regularly deal, expressed much interest in my argument. (A person is about 15 times more likely to be struck by lightning in a given year than to be killed by a stranger with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or chronic psychosis.)

With the exception of journalist Tim Williams who interviewed me for NewsTalk Florida, I don’t think any of the others believed me.

A Washington Post/ABC poll found – as Slate put it in its headline – “More Americans Blame Mass Shootings on Mental Health Than on Gun Laws.”

“77 percent, said better mental health monitoring and treatment would have averted Parkland.”

This is the prevailing attitude even though repeated studies prove otherwise. Why?

(3-2-18) From My Files Friday: Whenever a mass shooting committed by a young person happens, the third question asked is about his parents. (The first two are generally about whether the shooter had a mental illness and talk about gun control.)

Alleged Parkland, Florida, school shooter, Nikolas Cruz, and his younger brother were adopted by Roger and Lynda Cruz. Roger died when the boys were young, leaving Lynda to rear her boys as a single mother. She first called the police about Cruz when he was 10 years old. It was one of dozens of calls during the next decade. Lynda died last November.

I’ve read articles blaming her. They are similar to comments after other mass murders, especially those that involve a young shooter with a mental illness. Surely the parents knew. They could have done something. They are to blame.

I don’t know enough about Nikolas Cruz to speak specifically about his childhood, but complaints about his mother reminded me of an Op Ed that I wrote for USA Today in 2011 after Jared Loughner shot U.S. Representative Gabrielle Giffords and eighteen others in a Tucson suburb. In that case, Loughner had a mental illness and there were warning signs.

These are comments I’ve heard and read on the Internet about Randy and Amy Loughner, whose son has been charged with shooting Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, D-Ariz., and 12 others, and killing six bystanders.

It’s unlikely the parent’s statement — that they “don’t understand why this happened”— will soothe the criticism and public anger aimed at them. But as the parent of an adult son with a severe mental illness who has been arrested, I can sympathize with the Loughners and testify that there are reasons why a parent can be caught off guard.

(2-27-18) In this final snippet conducted by SAMHSA’s Gains Center, I describe how horrible mental illnesses are and how fortunate I am that my son Kevin is doing well today.

What helped him?

He finally accepted his illness and was given the tools that he needed – housing, a job, a purpose, and hope. I talk about recovery and note that we still don’t know how to help everyone recover, some don’t and often end their own lives, but we must have hope that someday everyone will. There was a time when I thought Kevin wouldn’t get better. Now he is doing fantastic and I am grateful that he allows me to continually share his story.

(Please note, that while my mind was telling me that Kevin had gained 20 pounds on medication, my mouth said he had gained 200 pounds. An embarrassing mistake. I apologize Kevin and want everyone to know that you did not gain 200 pounds!) Thanks to SAMHSA’s Gains Center for interviewing me.

"Pete Earley is a fair-minded reporter who apparently decided that his own feelings were irrelevant to the story. There is a purity to this kind of journalism..."

- Washington Post"A former reporter, Mr. Earley writes with authenticity and style — a wonderful blend of fact and fiction in the best tradition of journalists-turned-novelists."

- Nelson DeMille, bestselling author"A terrific eye for action and character. Earley sure knows how to tell a story. Gripping and intelligent."

- Douglas Preston, bestselling co-author of The Relic

Pete Earley is the bestselling author of such books as The Hot House and Crazy. When he is not spending time with his family, he tours the globe advocating for mental health reform.

As a former reporter for The Washington Post, Pete uses his journalistic background to take a fair-minded approach to the story all while weaving an interesting tale for the reader.

Sign up to receive blog posts and the latest from Pete including new books and resources.

Copyright © 2026 · Education Child Theme on Genesis Framework · WordPress · Log in

There’s no controversy here. People with psychotic disorders sometimes don’t know they are suffering from a mental illness, and there really is nothing to argue about. And yet, the word “anosognosia”—meaning the patient is unable to see that he is ill—is a charged word.

Why is that? Let me talk a little about the history of this word and the political meaning it has taken on.

Anosognosia is a term that was coined in 1914 by a Hungarian neurologist named Joseph Babinsky. Babinsky noticed that sometimes after a stroke, people are unaware of their deficits. This is presumed to be a result of pathophysiologic changes in the brain, and not the psychological defense mechanism of denial. There is not a precise anatomical finding that predicts anosognosia: you can’t look a patient with anosognosia and say, “ah, the MRI will show a lesion in X area of the brain.” Though certainly, some deficits are more likely to include anosognosia than others.