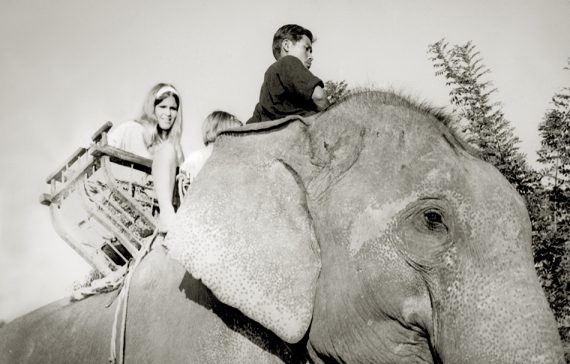

Justice Stratton as a teen.

(10-22-18) “Everybody has the power to make a difference. It can start with one small thing. Don’t think you have to join a big organization to save the world. Start small. Make a difference in one person’s life. You get to a mile inch by inch.”

One of the greatest joys in my life is working with incredible advocates. Justice Evelyn Lundberg Stratton is one of them.

She was serving on Ohio’s Supreme Court when we met. Both of us were on the board of the Corporation for Supportive Housing and I was immediately impressed. She eventually left the board and resigned from Ohio’s top court, in part, to focus on implementing the Stepping Up Initiative in all of Ohio’s 88 counties. It’s a national effort to help communities end the inappropriate incarceration of individuals with mental illnesses.

I spent this morning (Monday) speaking at the Stepping UP Initiative Ohio statewide conference. The Buckeye State is becoming a national model for jail diversion.

More than 10,000 law enforcement officers in the state have received Crisis Intervention Team training. Ohio has created a Veterans Justice Program to insure veterans get individual care and are connected with meaningful services. Ohio counties are using the sequential intercept model (co-created by Dr. Mark Munetz – another wonderful advocate in Ohio) to identify and intercept persons caught in the criminal justice system and direct them into services. Ohio has created a Benefit Bank that links persons with resources to meet their needs. There also is a “compassion map” that identifies the 67,000 non-profit and faith based programs in Ohio by county to facilitate networking and community collaboration between organizations that control $140 billion in assets.

Ohio State Alumni Magazine recently published a cover story about Justice Stratton. Take time to read it. She’s been lost in the jungle for hours at a time, ridden an elephant during a stampede, and competed in goat tying contests in rodeos!

She is one of the most inspiring advocates I know.

One Woman’s Calling To Connect

Written by Todd Jones, photos by Jo McCulty, published in Ohio State Alumni Magazine

There are no windows in Meeting Room B in the basement of John McIntire Library in downtown Zanesville, Ohio. Fluorescent lights cast a pallid tone, heightened by blank, beige walls. The space is functional, but far from the ornate hall of the Ohio Supreme Court, where Evelyn Lundberg Stratton ’79 JD presided for 16 years before resigning as a justice in 2012 with two years remaining in her term.

She made the career move to better quench a thirst for advocacy, which on this morning has led her to a rented room in the seat of Muskingum County, where she sits at a folding table and eats lunch from a paper plate with plastic utensils.

Stratton doesn’t want to be anywhere else.

About 30 people from the county’s social services agencies, judicial system, law enforcement, medical fields and higher education have gathered to hear her speak about The Stepping Up Initiative of Ohio, the state’s partnership with a national program aimed at reducing the number of people with mental illness in jail. As project director, she has visited more than half of Ohio’s 88 counties in the past two years to extol and explain the initiative, and 41 have passed resolutions to implement it.

Muskingum County has already signed on, but Stratton has returned to provide details about the six-step planning process and tools available to the true heroes, as she refers to those gathered before her today. She’s also here to ignite their coals with her own fire.

“Everybody has the power to make a difference,” Stratton tells those assembled. “It can start with one small thing. Don’t think you have to join a big organization to save the world. Start small. Make a difference in one person’s life. You get to a mile inch by inch.”

At 65, Stratton is a hummingbird in scuffed high heels.

She blinks, fidgets, gestures for emphasis as her words flow forth in a torrent, no notes or microphone needed. She could have presented this information in an email or conference call, but Stratton — “Call me Eve,” she says — made the one-hour drive from her home outside Columbus to look people in the eye, listen to their concerns, introduce them to one another, cajole them to converse, offer advice, bridge all gaps. It’s not a performance, for that suggests insincerity. Instead, this child of Christian missionary parents, who was born and raised in Southeast Asia, knows no other way. She calls the work she’s doing now her mission, and so today there is zealotry in Zanesville. Veterans of Stratton meetings chuckle at a description of the day, for they know well what it’s like to be in a room with the former justice in full flight.

“She’s a force,” says former Ohio Supreme Court Justice Yvette McGee Brown ’85.

“She’s a dynamo,” declares Tracy Plouck ’97, director of the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.

“She’s relentless,” says Tom Stickrath ’79, who heads the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BCI).

Thom Craig has spoken alongside Stratton more than 40 times since Stepping Up launched in 2015. She has met him each time with a warm greeting, and she listens intently to his speech as if she’s never heard of this topic before.

Stratton first felt a calling to advocate for people with mental illness —many of them juveniles and veterans — as a trial judge.

In seven years on the Franklin County Common Pleas Court bench, she saw many of the same individuals recycle through on charges. Instead of falling prey to cynicism, the self-described “doer” sought system reform through collaboration. As director of the mental health program for Peg’s Foundation, a sponsor of the privately funded Stepping Up Initiative of Ohio, Craig has never seen a hint of negativity in Stratton.

“She always sees a way,” he says. “Maybe that’s because she’s seen so much.”

Her past as prologue

Mementos of a happy personal life and sparkling career decorate Stratton’s small, tidy office at Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease, the Columbus law firm where she has provided counsel part-time, behind the scenes, since leaving the Supreme Court five-and-a-half years ago. Photos of her husband, Jack Lundberg, and two adult sons, Tyler and Luke Stratton, are intermingled with awards, including the prestigious Ellis Island Medal of Honor and a trophy with this inscription: “LeTourneau College Girls Goat Tying, First Place, 1972.”

Yes, she once tied goats in a rodeo.

Here, too, are statues of elephants, paintings of leopards, lions and zebras, and a photograph of her father, Elmer, on the Mekong River, a reminder of her upbringing in Southeast Asia.

“If I died tomorrow, I will have lived more lives than most people ever get a chance to,” Stratton says. “I remember thinking that 20 years ago. Because of that, I feel like I have an obligation to give back.”

Stratton’s passion for advocacy stems from her parents’ missionary work, but it’s been shaped by her own life experiences.

As a child in Thailand, her house was a bare wooden structure with no running water or electricity. Pythons and boa constrictors were common. After age 6, she lived apart from her parents for nine months at a time while attending boarding school in war-torn Vietnam. She was 14 when the Tet Offensive escalated safety concerns in 1968, prompting the family to evacuate to Bangkok. It wasn’t the last time danger breathed down her neck.

She’s been lost in the jungle for hours at a time, ridden an elephant during a stampede — “They rock back and forth sideways,” she reports — and rope-climbed mountains in Malaysia. A school bus once forced her car off the road on a campaign trip. As a trial judge, a death threat prompted Columbus police to tail her with protection for a short period. She keeps a reminder of that time: a tiny replica of a tombstone, bestowed by a fellow judge with a similar sense of humor.

“Nothing fazes me,” Stratton says. “I’m not afraid of any problem. I’ll tackle it.”

Stratton also showed ferocious determination while breaking into the male-dominated field of law. She applied for numerous jobs in her first six months after graduation. No, she kept being told. “I kept interviewing and interviewing because I loved it, and I knew I’d be good at it,” says Stratton, who eventually was hired by a small Columbus law firm.

She took cues from the book Dress for Success, plowed hours into cases, impressed others in the courtroom with her preparation and networked persistently, even with adversaries. She wanted to be a judge by age 50.

“There’s no explanation why, other than it was my calling,” Stratton says. “It just felt like that was what I was supposed to do with my life.” In 1989, she became the first woman elected to Franklin County Common Pleas Court. She was 34.

“To some extent, she got tested by the lawyers because of her youth,” says Michael Close ’67, a fellow Republican elected to the same court that year. “Eve had to be tough. She had to learn when she had to make the calls and when she could bend. She did a fine job.”

Stratton learned how to get things done, sometimes enlisting Close to introduce her ideas about court administration so there’d be less pushback from older, male judges. This woman prosecutors dubbed “The Velvet Hammer” for her tough sentencing in white-collar crime cases wasn’t afraid to do what she thought necessary.

She never buckled under her workload, which grew like spring weeds after Gov. George Voinovich appointed her to the Ohio Supreme Court in 1996. She later earned three six-year terms from voters.

Dave Smith, her friend and volunteer driver for nearly 30 years, removed a bench seat from the back of his black Chevy van and installed a countertop desk so she could read legal briefs and write on the road. “We’d go to a campaign dinner or fundraiser in Cleveland or Akron or wherever and she’d get back in the van at 10 o’clock at night,” Smith recalls. “She’d take a 5- or 10-minute nap, and then she’d get up, turn the lights on and work the rest of the drive home. It didn’t matter what time of night it was, she’d work.”

Despite loving her role as a justice, the work closest to Stratton’s heart increasingly involved improving a judicial system swollen with repeat offenders experiencing mental illness. “I had several family members over the years suffer from mental illness, and I saw what it could do to a family,” she says. “As a trial judge,

I had so many cases involving the mentally ill. They didn’t belong in the system, but I didn’t know what to do with them.

The more I researched it and talked to people involved, I realized there was a huge need. It was an area without much leadership. People have a passion for cancer or diabetes, but mental illness didn’t have a political voice. I felt I could make a difference. The veterans courts were an extension of my mental health work, and working with juveniles was another version.”

Stratton formed and chaired committees to combat the challenges. After learning that her early strategy of jailing those convicted most often led to costly recidivism, not necessary treatment, she created an atmosphere of acceptance for mental health courts that took into account the complicated issues involved. The work led to the creation of 44 mental health courts and 23 veterans courts in Ohio. Her time kept evaporating until 2012 when she had one of her “eureka moments,” which occasionally come out of the blue to offer a clear path. Stratton concluded her calling to help provide mental health services to offenders would best be pursued as a private citizen.

“Think of how courageous it was for her to leave the Supreme Court,” McGee Brown says. “Most people can’t wait to get into those seats and stay forever.”

Instead, Stratton couldn’t wait to get into the community at large and build small communities bonded by a just cause. “I was unleashed,” she says.

Her Stepping Up colleague Craig says Stratton has rewired, not retired.

Some mornings, she wakes up without an alarm clock, “my mind going so much I’ve got to get up and deal with it.” Carrie Marioth, legal secretary at Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease, says Stratton’s schedule is “bonkers.” Problem-solving often has her meeting with county officials somewhere around the state, GPS required. For events outside Columbus, she still works in the backseat while Smith drives her Ford Escape. “We’ve got two cell phones, an iPad and a laptop going in the car at all times,” Smith says. “The phone doesn’t stop ringing, and she doesn’t stop answering emails, from the minute she gets into the car until we get back home. It wears me out. She’s passionate about what she’s doing, and I think when you’re passionate about something, you find the energy to do it.”

She also has passion and energy for the practice of law, and about one-third of her time is spent as counsel with Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease, a job she’s held since early 2013. She works with the firm’s clients -and sometimes outside companies and law firms throughout the countryin an advisory role that she sees as a direct application of her Ohio State education.

“I am basically an appellate coach,” Stratton says. “I try to make excellent lawyers even better. I help them shape their arguments, craft their briefs, and they practice their oral arguments with me pretending to be the judge to prepare for cases. It’s a lot of fun. I like the complexity of the difficult legal issues. I like pitting my mind and training against the best way to craft an argument. I find it very satisfying professionally and emotionally.”

Although no longer a justice, Stratton’s advocacy work still occasionally lands her in the halls of state power, where her renowned reputation for personal connection and communication command attention — and ignite action. “She does not take no for an answer,” Plouck says. “If you want to move an initiative forward, she is an excellent partner to have.”

Seeing a person instead of a title enables Stratton to keep party lines from walling off progress. McGee Brown, a Democrat, says it was clear that Stratton viewed herself as a public servant, not a politician, when they served together on Franklin County Common Pleas Court and the Ohio Supreme Court. “As a colleague, she was great to work with,” McGee Brown says. “Eve and I didn’t always agree, but it was never in a disrespectful way.”

Stratton, shown here at a meeting in Columbus with law enforcement officers representing 83 counties, joins forces with officials at all levels of government to further the causes of people with mental illness.. Photo by Jo McCulty

A connector in her element

“In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer.”

This quote by French philosopher Albert Camus is one of Stratton’s favorites, fueling 60- and 70-hour work weeks despite being of retirement age. She’s set a goal to give up Saturday and Sunday work within the next two years, and there are means of escape. Her husband, whom she credits for his abiding support in all her endeavors, is building a home they will share in the Montana wilderness. While the house is under construction, the couple retreats to a rustic 10-by-10-foot cabin on the land they’ve owned for three years. They’ve been fly-fishing in Chile and Costa Rica, and they enjoy traveling to see Stratton’s sons, Luke, a light and sound director for music shows who lives in Denver, and Tyler, an assistant film and TV director in Los Angeles. At home, Stratton cooks Thai food, works in the garden, paints and writes poetry and science fiction stories.

Yet one pursuit tugs at her heart and demands her time more than most others.

“She really likes getting people together in a room, talking about a problem and getting them to move forward on it,” Tyler says. “She has this great ability to get people to want to do stuff they didn’t know they wanted to do. Her way is not to play hardball with them; it’s more like kill them with personal attention.”

Stratton is in her element on this morning in Zanesville, walking out from behind the podium, pointing to people, prodding participation in the library basement. She asks all 30 who they are and what they do, and responds each time by rattling off suggestions about who in the room could help whom and how.

Brian Wagner, executive director of the Muskingum County Community Foundation, mentions a grant. “Now here is a person who said he’s here to help,” Stratton tells the others, “and he has money!” Laughter fills the room. “A little money,” Wagner clarifies. “I’ve learned you don’t get unless you ask,” replies this contingent’s connection maker.

Stratton’s idea of leadership is to empower others. She says for some unknown reason she’s always been able to see — often in ways others don’t — who should be in a group and how they should be linked. Her job is to make everyone coalesce, no matter their diverse agendas. With that intention, a sense of accomplishment is palpable on a rainy morning in Muskingum County as the two-hour meeting closes with applause. Zanesville Municipal Court Judge William Joseph approaches Stratton. “What you are doing is wonderful,” he tells her.

As the room clears, Stratton collects her Stepping Up brochures, lifts her briefcase and, in uncharacteristic fashion, heads slowly down the hall. A day earlier, she spoke in Columbus to law enforcement officers from 83 counties at a Buckeye State Sheriffs’ Association gathering. Several thanked her after that presentation, in which she shared a similar swirl of names, program details and suggestions for dealing with mentally ill criminals. Now, less than 24 hours later in Zanesville, Stratton gets on the elevator and lets out a sigh. “I always feel like a balloon deflating after one of these,” she says.

The feeling doesn’t last. Zanesville is barely in the rearview mirror when Stratton — papers spread around her in the car’s backseat — puts in her earbuds and joins a conference call as the miles roll by on Interstate 70. Home beckons in Columbus, where on a small scrap of paper in her office desk is an unattributed quote, one she considers a good motto to live by.

“Life should NOT be a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely in an attractive and well-preserved body, but rather to skid in sideways, mango juice in one hand, chocolate in the other, body thoroughly used up, totally worn out and screaming ‘WOO HOO — what a ride!’”