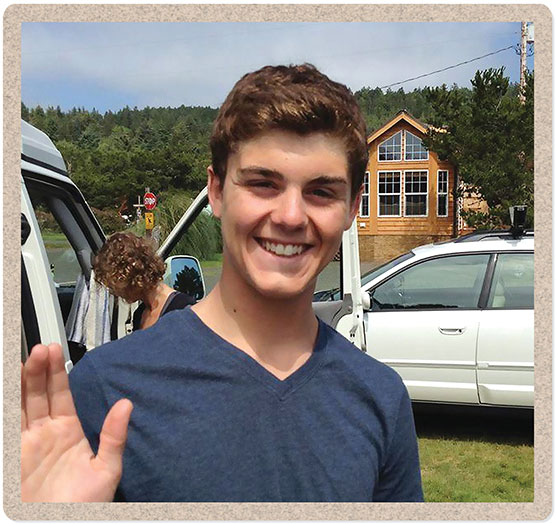

Happier Times. Photo courtesy of Jerri Niebaum Clark

(11-16-21) Jerri Niebaum Clark embodies the famous Margaret Meade quote: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

My Son’s Journey: Part One

A Mom’s Journey Through Mental Illness, Suicide and Advocacy

First published in Kansas Alumni Magazine, University of Kansas.

I studied journalism with no idea that the most important story I would ever tell would be the tragedy of my own family.

My son, Calvin, was a happy baby, a solid student, a successful athlete. He grew into a clever, curious, compassionate person. He also developed a serious mental illness in his teen years that devolved into psychotic episodes. A mental health care system in disarray meant that instead of helpful care, our family met heartbreak.

In disbelief, I watched my son’s world tilt away from a bright future punctuated by academic accolades and toward incarcerations, suicide attempts and hospitalizations in locked wards that didn’t make him better. Along the way, the everyday bad news cycle got personal. I’m not at all surprised that homelessness and suicide rates are rapidly rising or that so many police encounters end tragically. These are preventable social ills, but our service systems are not built to prevent them.

Families like mine strive to keep loved ones from hitting rock bottom, discovering that there really is no bottom and that help doesn’t prevent but instead requires a radical free-fall. I watched my son delivered into society’s underbelly by design. He spent months homeless, met law enforcement again and again, and tried multiple times to die. These traumas are part of a tragic inventory of the requirements for public assistance when someone has a serious mental illness. Calvin was 23 when he died from suicide March 18, 2019.

As I try to reconcile what happened to my son and our family, I have been compelled to dust off my journalism skills to write and holler my way into public view.

Calvin body surfed in Hawaii in 2016. His tattoo says, “Surf Your Waves.” Photo courtesy of Jerri Niebaum Clark.

While I work, the title of a book by Ron Powers spins me like the stanza of an unlikable but unshakeable song: No One Cares About Crazy People. Powers fathered two sons who developed schizophrenia and lost one to suicide. His book is among a dozen or so by family members whose children have gotten sucked into the void of serious mental illness. I’ve contacted most of those writers, including Pete Earley, who wrote Crazy: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness. Like Powers, Earley and other families in this fight, I refuse to let people not care.

I also refuse to slink away in despair.

When I was new to advocacy, I posted a quote from Anne Frank above my computer: “How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.” When I doubt whether my voice will ever matter, I consider that quote, take a breath and get back to work.

I testified in the Washington State Senate for the first time January 18, 2019, when I believed there was still time to influence changes that might save my son. Lawmakers were reconsidering the Involuntary Treatment Act (ITA), a state law that determines criteria for behavioral health intervention. My hands were shaking as I held my printed speech. I leaned toward the microphone, made eye contact with the senators and tried not to cry as I began: “ITA law in Washington State traps an individual in an illness state so that the only way out is through violence.”

This statement was not hyperbole. A scene that haunts me still is a night when Calvin was on our back deck in the dark, swinging a large stick and “preaching.” On the patio table he had assembled bizarre altars built with playing cards from the Magic: The Gathering game, sticks and bits of food. He was interacting with unseen individuals, speaking words that were loud but not really intelligible. I encouraged him to come inside. His eyes were wild and dark. He didn’t hit me, but I was afraid when he blocked me with the stick and said, “Stop!” He was there, but not there. As I slipped inside to call for help, his manic raging continued.

“It’s not illegal to be psychotic,” she said.

The disinterested county crisis responder on the phone suggested I lock my bedroom door and use earplugs to sleep. “It’s not illegal to be psychotic,” she said, clearly reciting something she had said many times. She explained why she wouldn’t do anything to help: “We’re protecting your son’s civil rights.” If he hurts someone or himself, she went on, then call police. I connected the dots in my head: My son had the civil right to avoid the hospital, but protecting that right put him at risk for arrest and possibly jail. To restore him to sanity, we would have to catch him in a narrow window between violence and crime.

There were so many times that the madness of mental illness policy crashed full force into my family. Calvin’s treatment took many wrong turns because of systemic disorganization, discrimination and underfunding. Still, I often circle back to the brokenness of that pivotal moment when we had no idea how to help our super-sick son and were told that violence and crime were the missing elements for intervention. Most infuriating was the smug crisis responder’s position that this lack of help served my son’s best interest— to protect his “civil rights.”

Civil libertarians who might be reading, please settle down. I’m one of you.

I believe in the right to agency and self-determination. What I have learned in the harshest way possible is that when someone is that sick, agency is already gone—stolen by the disease. Involuntary treatment is the only kind. A mind so unwell cannot see its illness or a need for care. A person as sick as Calvin was that night is not saying “no” to treatment but instead is leaning into an alternate reality where Magic: The Gathering characters come to life and the world is on fire with excitement and opportunity. Of course, I suggested we go to the hospital that night. My offer made absolutely no sense to my delusional son.

Years later I learned the term anosognosia—a symptom of brain-based disease when a person is unable to “see” the illness because of disordered connections in the brain itself. When he was symptomatic, Calvin had no idea he was crashing toward disaster. As his mother, I saw clearly what was coming, just like knowing a small child who darts into the street is going to get hit one day. I had no power to prevent any of it.

(Tomorrow: Part Two – Turning pain into advocacy.) This story is being reprinted with permission from Kansas University Alumni Magazine.

Calvin, Jerri and Matt hiked near Lake Sammamish on Christmas Eve 2017. Photo courtesy of Jerri Niebaum Clark