(9-24-21) A frustrated Virginia sheriff’s deputy recently threatened to arrest employees at a state mental hospital because they balked at admitting an individual who was in the midst of a mental health crisis. The deputy had arrived without first having the patient cleared by a medical doctor for transport and without any medical records, including whether the patient had been tested for COVID.

The deputy’s action is an example of the latest sad twist in Virginia’s ongoing mental health crisis.

With private hospitals turning away patients and state mental hospitals lacking capacity, law enforcement officers are stuck dealing with patients who have no place to go.

This is wrong, but so far the state’s leaders have failed to find a way to resolve a lack of psychiatric services and hospital beds.

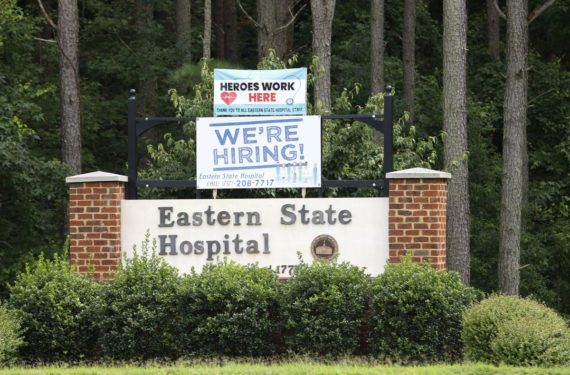

In July, five state mental hospitals stopped accepting patients because the hospitals didn’t have adequate staff to help patients. Many employees had quit because of COVID. There were other contributors such as poor pay.

At that time, I wrote an OP Ed in The Washington Post that criticized private hospitals. As I explained, most Virginians experiencing a mental health crisis are taken to emergency rooms under a temporary detention order (TDO), which permits the hospital to hold them for up to 72 hours for their own protection if they meet certain criteria, such as being dangerous or exhibiting self-harm.

In 2017, there were 25,852 Virginians hospitalized under TDOs. Most were treated at private hospitals and released within days. Only the most ill were sent to state mental hospitals for extended care. The number of TDOs dropped last year to 24,125 patients. Yet admissions at state hospitals have ballooned and are now overloading the system.

One reason for this influx is a well-intentioned 2014 law.

Under a “bed of last resort” law, state mental hospitals must accept any psychiatric patient that a private hospital turns away. The law was enacted after state Sen. Creigh Deeds (D) rushed his 24-year-old son, Gus, to a crisis center only to be told workers couldn’t find a local available psychiatric bed within the 72-hour TDO period. Sent home, Gus slashed his father’s face with a knife before ending his own life.

Before the 2014 law, private hospitals accepted 90 percent of all TDO patients. Last year, that number fell to 75 percent. The coronavirus pandemic is partly to blame because some hospitals are now using psychiatric beds for coronavirus patients. But so is greed. Psychiatric beds historically are money losers. Surgical beds are hugely profitable. Private hospitals began cherry-picking patients.

The Northern Virginia Mental Health Institute in Falls Church opened in 1968 as a short-term state mental hospital with 94 beds designated for patients needing acute care. Before the 2014 law, 20 percent of its patients were admitted under TDOs. Today, 90 percent of its patients are under TDOs sent by local private hospitals, often for flimsy reasons — “patient can be better treated by state.” A recent study found Virginia private hospitals dumping TDO patients with “severe burns requiring acute care, unstable seizures, acute respiratory distress, intravenous fluids or IV antibiotics that the state facilities are simply not designed, equipped, or staffed to treat.”

Patient dumping by private hospitals and inadequate staffing at state mental hospitals has put sheriff’s deputies and police in the middle of a dilemma that is not of their making. What’s happening is dangerous and not good for patients. Law enforcement officers are not doctors and simply driving someone in crisis to a state hospital who has not been medically cleared for transport, without medical records, or being checked for COVID, puts everyone at risk.

Virginia’s elected officials and state employees must find a solution – and soon.