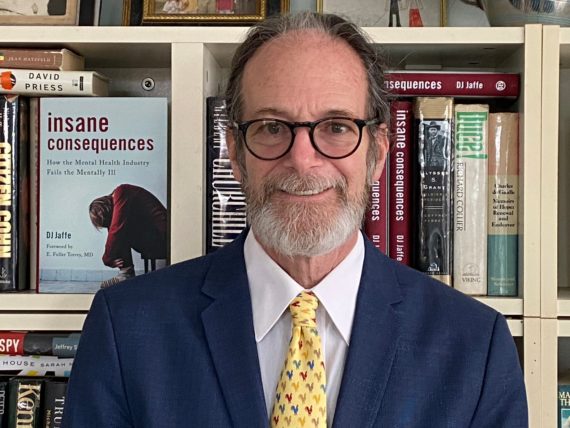

Credit…Paula Orndoff

Credit…Paula Orndoff

(9-23-20) Fans and friends can attend a virtual memorial service for D. J. Jaffe tomorrow (9-24-20) hosted by the Manhattan Institute from 1 p.m to 2 p.m.. (Register here.) During the first half hour, I’ve been asked to speak about the impact of D. J.’s advocacy along with several others, including John Snook, executive director of the Treatment Advocacy Center. The second half hour will be a discussion about policy changes that he promoted.

The Manhattan Institute has posted comments honoring him by Dr. Elinore McCance-Katz, Dr. E. Fuller Torrey, and his other friends here.

“The passing of DJ Jaffe is a great loss—the loss of an important leader and untiring advocate for the seriously mentally ill, but also the loss of a teacher and a friend. His contributions will live on and those of us who shared his vision for addressing serious mental illness in our country will do our best to continue in the footsteps that he forged,” Dr. McCance-Katz, the assistant secretary at HHS for mental health and substance abuse wrote.

I am reprinting D.J.’s obituary from the New York Times.

Ad Man Turned Mental Health Crusader, Dies at 65

While DJ Jaffe was working as an advertising executive on Madison Avenue, he and his wife became the caretakers of his wife’s half sister, who had moved from Milwaukee as a troubled teenager to live with them in their Manhattan apartment. Before long she became catatonic. She was later found to have schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

The experience plunged Mr. Jaffe, who died on Aug. 23 at 65, into the world of mental health, which he soon came to see as dysfunctional.

It also turned him into a crusader. Even as he pursued a successful three-decade advertising career, he became a powerful voice and lobbyist for people with profound mental illnesses.

Provocative and blunt-spoken, he became the driving force behind Kendra’s Law, a controversial measure passed in New York State in 1999 that authorized the courts to mandate outpatient psychiatric treatment for people who might pose a danger to themselves or others. If they fail to comply, they can be seized by police and hospitalized for a three-day lockup period.

Critics argued that the law impinged on the civil liberties of these patients. And by 2005, racial disparities were reported in its use, with Black people five times as likely as white people to be subjected to it. But it was also hailed as reducing homelessness, suicide attempts, hospitalizations and incarcerations.

On the federal level, Mr. Jaffe was instrumental in the passage of the Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act of 2016, which made available psychiatric, psychological and supportive services for people and families in crisis.

His brother Robert said Mr. Jaffe died of complications of leukemia at his home in Harlem.

Mr. Jaffe was a fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, a conservative research group that studies urban affairs. He promoted some ideas that he called politically incorrect — that some people never recover from mental illness, for example, and that seriously mentally ill people are often violent.

He was also the author of “Insane Consequences: How the Mental Health Industry Fails the Mentally Ill” (2017). The book, an indictment of the system, said that while billions were spent on mental wellness for the general population, programs for those with the most serious mental health issues were vastly underfunded.

He further wrote that the criteria for involuntary commitment were being so narrowed that laws were essentially requiring people to become violent before they could be ordered into treatment. Mr. Jaffe espoused what he called “treatment before tragedy.”

Don Lyle Jaffe was born on Nov. 21, 1954, in New Rochelle, N.Y., to Saul and Phyllis (Stohn) Jaffe. His mother was a stockbroker; his father owned a commercial photo lab. Mr. Jaffe, who went by DJ, grew up in nearby Edgemont, a suburb north of New York City. He graduated from New York University with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in accounting in the late 1970s.

Mr. Jaffe was recruited by Coopers & Lybrand, the accounting firm, which later became PricewaterhouseCoopers, and he moved to Chicago. Only then, by his account, did he realize that he hated accounting. After putting out the word that he was available, he was recruited by an advertising agency and moved back to New York.Over time, he worked for the agencies Gotham Inc., SSC & B Lintas, Foote Cone & Belding, and Leo Burnett. His accounts included Coke, Citibank, United Airlines and the U.S. Postal Service, his brother said.

He married Rose Wagner, who managed women’s fashion boutiques, in 1991 and soon became involved in caring for his sister-in-law, Lynn Gommermann, and fighting the mental health system.

Employers gave him time off to lobby government officials, conduct media interviews, attend conferences, give TED talks, testify before Congress and speak at the Trump White House. In 2011 he founded Mental Illness Policy Org., a clearinghouse of information for policymakers and the media, and was its executive director.

His wife died in 2018. In addition to his brother Robert, he is survived by another brother, Jay. He provided for Ms. Gommermann, his sister-in-law, in his will, his family said. She now lives in Milwaukee.

Mr. Jaffe met Paula Orndoff, a filmmaker and producer, in April 2019. They were married in his room at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan on Aug. 14, nine days before he died. Because of the coronavirus, friends and relatives attended the ceremony by Zoom.

Katharine Q. “Kit” Seelye has been the New England bureau chief, based in Boston, since 2012. She previously worked in the Washington bureau for 12 years, has covered six presidential campaigns and was a pioneer in The Times’s online coverage of politics.