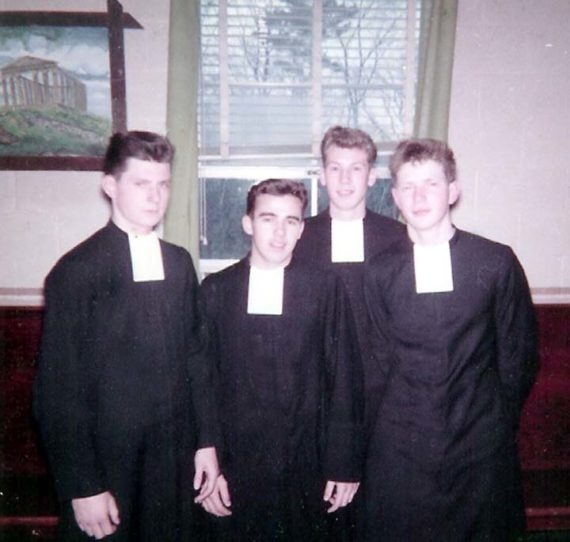

Four Novices in Esopus 1962 — 1963 Tom Mullen on far left. Marist College courtesy of Rick Mundy.

(4-28-20) News articles about how difficult it is for many Americans to practice social distancing and self isolation caused me to think of Thomas Peter Mullen, the founder of Passageway in Miami, Florida, and the valuable lessons that he taught me.

With pure white hair that tapered into an equally white beard and a fondness for wearing blue jeans with a tattered Navy blazer, Mullen lived modestly and enjoyed engaging in long discussion about morality, spirituality, and an individual’s mission and purpose in life.

I remember his staff at the halfway house that he ran keeping him occupied in another part of the building when a pharmaceutical rep dropped by with samples of the antipsychotic Abilify. Passageway operated on a barebones budget and the staff was happy to receive free samples, but they knew Mullen would go into a tirade if he encountered the rep. Mullen believed drug companies should give medicines free to those who needed them, not profit from their sales.

Mullen had grown up in a tough Irish Catholic neighborhood in the Bronx and after his father had been swept overboard and drowned during a nor’easter while fishing in the Atlantic, Mullen’s mother had asked the Marist Brothers, a religious order dedicated to helping the underprivileged, to take her grieving teenage son under its wing. He joined the order and was eventually sent to Miami where he ran a methadone clinic but soon got into trouble for permitting social workers to discuss the pros and cons of abortion with pregnant drug abusers.

He left the church to launch a halfway house in 1979 for seriously mentally ill felons being freed back into the Miami community. By the time we met, Mullen had overcome tremendous obstacles in keeping Passageway open, including having ten thousand residents sign a petition demanding that it be forced to move from the residents’ neighborhood after a newspaper disclosed its location.

Mullen was dogged and resilient – but this blog is about loneliness and forgiveness.

Let’s begin with a murder.

A troublesome client

Homeless and psychotic, LeRoy Clarkson* became convinced he was being spied on by a pedestrian, who happened to walk to work through an underpass where Clarkson slept in downtown Miami. He attacked the stranger one morning nearly beating him to death, was found not guilty by reason of insanity, and was sent to a state mental hospital. When his condition improved, he was released to Mullen’s Passageway house. The building was encircled by a tall chain link fence and staffed round-the-clock. Six years after the attack, a judge approved Clarkson’s release back into the community.

Mullen helped him find an apartment and Clarkson eventually met and fell in love with Daphne, who moved in with him.

Three years after leaving Passageway, Clarkson showed up unexpectedly one morning and asked to talk to Mullen.

“I did something last night,” he confessed.

“What’d you do?” Mullen asked.

“I murdered Daphne.”

A shocking discovery

Mullen and Lillian Menendez, Passageway’s program director, hurried over to Clarkson’s apartment, where they found Daphne lying on the bed covered with blood. She’d been beaten to death. When Mullen investigated, he learned that a psychiatrist had reduced Clarkson’s medication from 80 milligrams a day to 20 milligrams to see if Clarkson could get by on a lower dosage but hadn’t bother to monitor his patient.

Found not guilty again, Clarkson was sent to a hospital and years later Mullen agreed to let him return to Passageway. For three years, he did great, but the medications he was taking seemed to fail him and Mullen had to step in between him and another halfway house client when they got into an argument. Clarkson was returned to the state hospital.

“What happens to him now?” I asked Mullen.

Clarkson would stay at the hospital until he was ready to return to Passageway, Mullen replied.

“You’ll going to take him back?” I replied, clearly surprised.

“Why wouldn’t we?”

I said what appeared obvious: Clarkson had already had two chances. He’d spent six years in Passageway the first time around, had been released, and had murdered his girlfriend. He’d come back twelve years later, done fine for three years, and then become threatening again. While both breakdowns had been caused because of problems with his antipsychotic medication, I questioned why Mullen would want to put his program at risk taking Clarkson back. I reminded him of those 10,000 protestors who wanted his program shut down.

“How many chances would you want us to give your son?” he asked me.

I had told him how my son had broken into a stranger’s house to take a bubble bath during a psychotic break. Fortunately, no one was home, although the homeowners did press charges later leading to his arrest.

I felt embarrassed.

Mullen reached into a desk drawer and removed an intricate diagram that he had drawn one night in his apartment when he was pondering the “profound complexity of the human condition.” His diagram convinced him of an undeniable truth: None of us wants to be alone. None of us wants to be socially isolated.

So what group willingly accepts a seriously mentally ill convicted felon?

“To avoid being alone, human beings seek out relationships with others, either individually – as friends and lovers – or in families or by joining gangs, neighborhoods, clubs, or religious groups. The question then becomes: Where does the chronic mentally ill adult felon fit?”

The answer was nowhere.

“No group will accept him or her willingly into membership. What person wants to join with this mentally ill person in any kind of intimacy or trust? As a result, the most fragile of our brethren – the seriously mentally ill offenders – are the only ones without an escape from their aloneness. Among us all, they are the most alone, the most isolated.”

Passageway was on its way to becoming a national model for halfway houses with seriously mentally ill clients when I was researching my book, CRAZY: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness. While the Clarkson case was tragic, it was not typical. Most Passageway clients were able to move back into society without ever breaking the law again. Those few who weren’t, were treated much more humanely in Passageway than inside prison or a state hospital.

Mullen often was asked to reveal the ‘secret” of Passageway’s success.

“The core, the bottom line, for Passageway, the rationale for the righteousness and the continuation of our service, is this: to help these seriously mentally ill felons not be alone…We care about one another here. We are a community. That’s our so-called ‘secret to success.’ Many of our clients have burned out everyone else who was part of their lives – their parents, their siblings, their spouses, their children. Who do they have left? No one. That’s where Passageway comes in. It’s that connection, that caring – the fact that we tell these people that their lives matter regardless of what they have done – that makes our program work. We’re certainly not foolish about it. We’re aware of the dangers and we watch for them. But we don’t ever give up on anyone who is willing to work with us against their mental illness.”

At Passageway, he concluded, “We never say anyone has run out of chances.”

Tom Mullen gave hope to the hopeless. He showed them they were not alone. That their lives mattered.

Two years after my book was published featuring Mullen and Passageway, Mullen died from natural causes. He was 64.

”Tom made it his mission to give these souls an alternative to an unending cycle of homelessness and jail,” defense attorney Mel Black, a former Passageway board member, told the Miami Herald. “He was truly his brother’s keeper.”

His legacy at Passageway lives on today.

*a pseudonym for an actual person used for privacy reasons