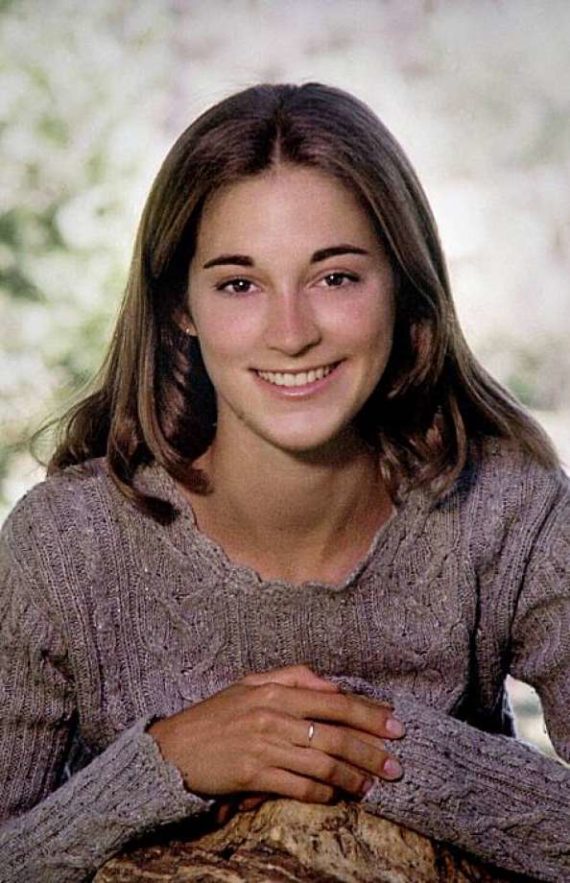

(Amanda Wilcox’s recent congressional testimony.)

(10-18-19) FROM MY FILES FRIDAY – Arguments about guns, the death penalty and mental health continue eight years after I wrote this blog about the death of Laura Wilcox and her parents’ reaction.

A Different View of Executing the ‘Insane’

Nick and Amanda Wilcox’s daughter, Laura, was nineteen, beautiful and talented. She was a sophomore at Haverford College, a Quaker school in Pennsylvania, and in the midst of a campaign for the student body presidency when she came home for Christmas Break in 2000.

Laura had worked during the summer as a receptionist at the Behavior Health Department in her hometown of Nevada City, California, which lies between Sacramento and Reno. When her boss called and asked if she could fill-in for a few days over the holiday season, she immediately agreed.

Her mother, Amanda, would describe her daughter to me this way when we first met last summer.

“Laura had extraordinary capabilities, kindness and spirit. She was an outstanding student, graduating as high school valedictorian and was attending a highly regarded college. She was extremely organized, disciplined and motivated; she had boundless energy. She lived life fully as she danced through her days, easily juggling academics, service work, clubs and student council, piano, ballet, and exercise. Laura touched and inspired everyone she met, she had a big circle of close friends; her teachers adored her. My daughter was beautiful, but her inner beauty was even greater. Her strong sense of compassion, respect, justice, and truth were beyond her years. All of that changed when she crossed paths with Scott Thorpe.”

Forty-one year old Thorpe had a severe mental illness and was growing increasingly enraged because he believed the FBI had ordered people to poison his food at a local restaurant and had forced him to see an incompetent psychiatrist.

On Jan. 10th, 2001, Thorpe reported for his appointment at the health department where Laura was working and, without saying a word, drew a semi-automatic pistol from his jacket and began firing.

Laura was shot four times at point blank range; twice in the chest, once in her hip, and once in her back. She died instantly.

Thorpe continued shooting, severely injuring Judith Edzards, a therapist, and killing Perlie Mae Feldman, a 68 year-old woman who had brought her ill brother-in-law, age 72, into the center.

Thorpe walked down the hallway while terrified workers hurried to lock doors.

In the break room, Pamela Chase and Ann Heinrich tried to hide behind an opened refrigerator door; and fearing for her life, Daisy Switzer jumped out her window, causing severe injury to her back and lower limbs.

After trying to open several doors, Thorpe left the building and drove to Lyon’s Restaurant, where he asked to see the manager, Mike Markel, whom he accused of trying to poison him a few days earlier. Thorpe fatally shot Markel. Moving into the kitchen, Thorpe repeated his accusation and shot the cook, Rick Senuty, who had been hired only three days earlier.

Word of the shootings spread quickly across the town. Schools were locked down and businesses closed. Residents frantically called each other because no one knew where the gunman would go next.

As it turned out, Thorpe drove home, took a nap, and eventually called his brother – a Sacramento police officer – and confessed to his crimes.

So far, this story sounds painfully familiar. But what happened next, is not.

Prosecutors were shocked when they met with Nick and Amanda Wilcox. They assumed that Laura’s parents would be their best advocates in seeking the death penalty.

But Nick and Amanda, both devout Quakers, said they did not want revenge. Instead, they demanded to know why officials had overlooked the severity of Thorpe’s mental disorder and why he had access to weapons that enabled him to murder their daughter.

During an investigation, officials were forced to admit that Nevada City did not have a facility where someone as sick of Thorpe could get help and when he began to develop signs of extreme mental illness, public officials had decided that they didn’t want to involuntarily commit him because the county would have had to pay the costs of sending him to an out-of-county facility.

At the trial, Thorpe’s brother and sister-in-law testified that they had warned doctors at Nevada County Mental Health several times about Thorpe’s collection of unregistered guns. But the doctors had told them that there was nothing they could do about Thorpe’s constitutional right to own weapons. One doctor finally told them, “If you’re not happy about it, change the law.”

Four psychiatrists and psychologists testified that Thorpe’s mental health at the time of the killings made him “unable to distinguish right from wrong,” the legal definition of insanity under the 1843 McNaughton rule.

Although the psychiatrists did not agree on an exact diagnosis of Thorpe, with some considering his ailment schizophrenia and others calling it “nonspecific psychotic disorder,” four of the five mental health specialists agreed that the convicted murderer could not tell right from wrong at the time of the crime.

Thorpe was ruled “incompetent to stand trial” and sent to a forensic mental facility where he remains today.

Many parents would have been outraged by that ruling. But not the Wilcoxes. They called it an appropriate decision and turned their grief into advocacy.

They immediately began lobbying for passage of what became called Laura’s Law, which authorized assisted outpatient treatment in California and was patterned after Kendra’s Law, which I have written about before. Putting their daughter’s “face” on that legislation helped get it passed in 2002.

But the Wilcoxes didn’t stop there.

They opposed the death penalty, especially the execution of persons with mental illnesses, and they were convinced that there were other families who felt the same way even though their loved ones had been murdered. So Nick and Amanda began speaking out against executions.

In 2006, they joined my good friend, Mike Farrell, who played Capt. B. J. Hunnicutt on the M*A*S*H television show and is a long-time death penalty opponent, in speaking at a special course at U.C. Davis.

They began advocating for stricter gun control laws and more recently, they joined with a group called Murder Victims’ Families for Human Rights to call for an end to executions. That group partnered with NAMI recently to release a study called Double Tragedies: Victims Speak Out Against The Death Penalty For People With Severe Mental Illnesses.

I met Nick and Amanda at a news conference that was held to publicize the Double Tragedies report and I was impressed with their commitment to changing mental health laws and stopping the execution of persons with severe mental disorders.

“People think mental health care –well, it’s not my problem,'” Nick Wilcox said. “But it is your problem. Scott Thorpe’s mental health became our problem, became our community’s problem.”

The Wilcoxes attended what would have been their daughter’s graduation from college. They talked with their daughters’ friends and spent hours sitting on a bench dedicated to her memory at the college.

“I saw the graduates sitting in alphabetical order,” Amanda Wilcox recalled. “I saw where Laura would have been sitting, where she should have been sitting. She always wanted to change the world.”

In their daughter’s absence, Laura’s parents have taken up that call.

” We’re going to keep working on mental health and on reducing gun violence. Unfortunately, there’s plenty to do,” said Amanda.

The occasional barbs, especially from gun groups, about the Wilcoxes “just liking to see their name in print” stings but doesn’t stick, Amanda said.

Nick and Amanda Wilcox have refused to be silenced. I remember what Amanda told me the last time we spoke: “This kind of tragedy gives you a platform you wouldn’t have had, normally. I think it’s wrong not to use it.”