(5-14-19) I’m not interested in endorsing any presidential candidate nor getting involved in a conversation about partisan politics.

My focus is on seeking better mental health care for all Americans.

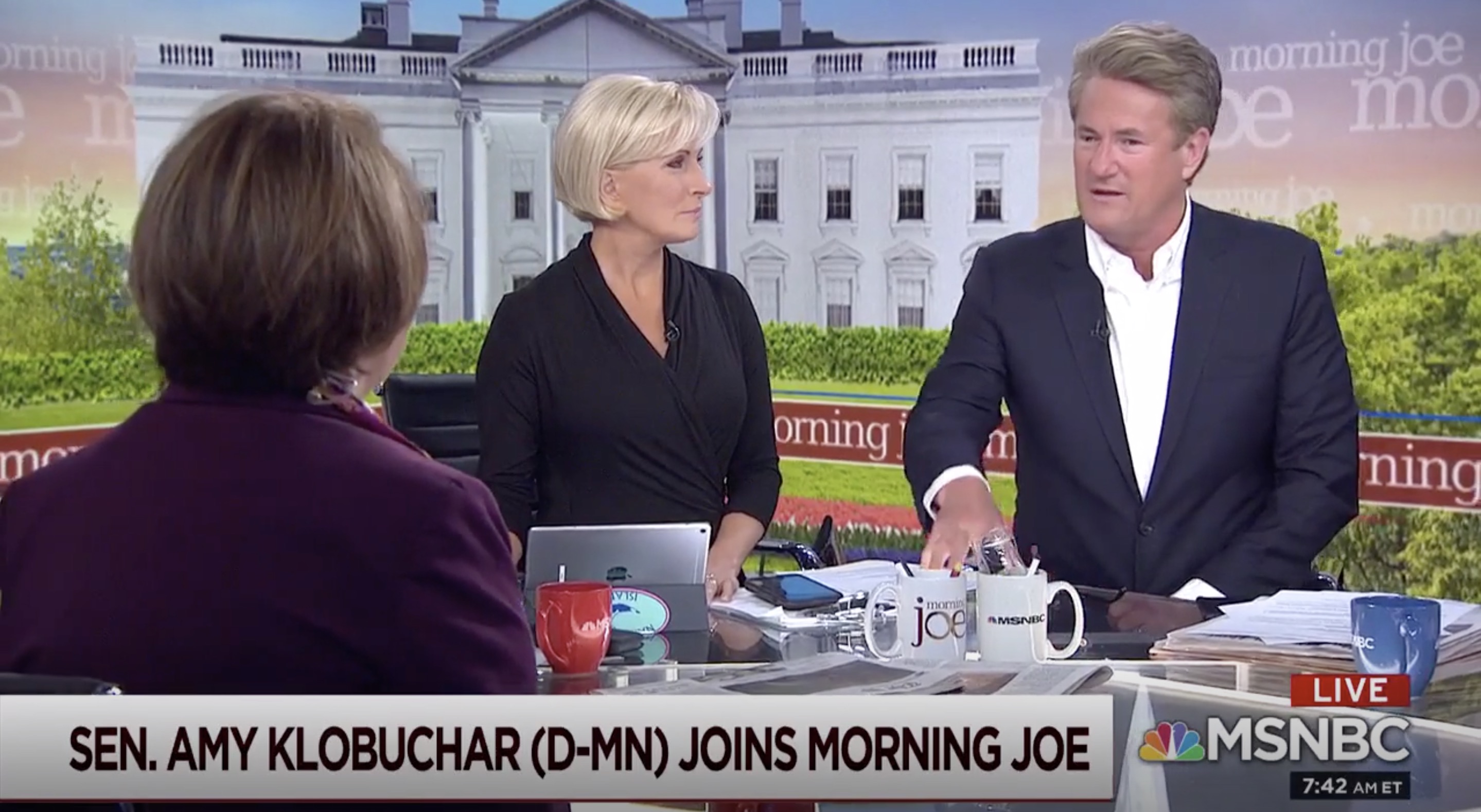

Last Friday, I happened to see Morning Joe on MSNBC when Democratic hopeful Sen. Amy Klobuchar (Minn.) was a guest.

She told the hosts and viewers that improving our mental health care system and addressing the opioid crisis were her top priorities. She explained how deinstitutionalization and a lack of proper funding for community care had lead to homelessness and the inappropriate incarceration of persons with serious mental illnesses. (Click here to view her segment.)

Ohio governor John Kasich mentioned the need for better mental health care during the 2016 campaign, as did Hillary Clinton, but Sen. Klobuchar is the first presidential candidate this time around, who I have heard, making it a priority.

During her televised appearance, Sen. Klobuchar spoke openly about mental health issues in her own family.

I realize that speaking about a father’s bouts with alcoholism is different from a candidate admitting to having a mental health or addiction issue. But contrast that openness about addictions and mental health, to the 1972 presidential campaign when Sen. George McGovern (D-S.D.) chose fellow Sen. Thomas Eagleton (D.-Mo) as his vice presidential running mate.

Sen. Eagleton suffered from bouts of depression throughout his life, resulting in several hospitalizations, which were kept secret from the public. When they were revealed, it humiliated the McGovern presidential campaign and Eagleton was forced to quit the race. His political career was over.

I find Sen. Klobuchar’s bravery about discussing her own family’s struggle inspiring and I am grateful that she “gets” mental health and addiction.

My hope is that all of the candidates in 2020 will follow her lead and discuss how they would improve our mental health care system and address addictions.

From the media:

The New York Times: Amy Klobuchar Proposes $100 Billion For Addiction And Mental Health

Senator Amy Klobuchar on Friday released a $100 billion plan to combat drug and alcohol addiction and improve mental health care, focusing one of the first detailed proposals of her presidential campaign on an issue deeply personal to her. Ms. Klobuchar — who has spoken before about her father’s alcoholism, including memorably at Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing — said she had developed the plan and made it an early focus in part because of that personal experience and in part because of the number of addiction-related stories she had heard from voters. (5/3)

Amy Klobuchar’s complicated political inheritance – The Washington Post

“Jim Klobuchar and daughter encounter new relationship.”

Amy, 58, shook her head and laughed, her short bob swaying side to side.

It’s been something of a theme over the course of Amy’s life; both an evolving kinship with her father and being mortified by things he put in the paper. For decades, Jim Klobuchar was a daily columnist for the Minneapolis Star Tribune; part sportswriter, raconteur-adventurer, voice for the voiceless, and needler of the ruling class. Little in his life, or Amy’s, was off limits.

Once, Jim had mentioned in a sports column that Amy had correctly diagnosed a football injury as being “groin”-related. That got her teased at school. There was the story Jim wrote about his divorce from Amy’s mother, Rose, the day after the split became official in 1976 (“My mom never liked that,” said Amy, whose mom died in 2010). And then, in 1993, there was the front-page article Jim had to write about his own arrest for drunken driving.

Amy was a young lawyer by then, and at one of Jim’s hearings to determine his sentence, she took the stand. But she wasn’t there to defend him.

“It was a prosecution,” Jim wrote later.

Amy had plenty of material to work with.

There was the time they drove to a bar after a Vikings game — he got tanked while she drank a 7-Up. The time he swerved his car into a ditch with her in the passenger seat. All the times he pretended the bottle he kept in his trunk was mouthwash, and the times Amy and her younger sister, Beth, sat in the room above the garage, staring out the window and waiting for him to come home.

“I reminded him of the birthdays he missed,” Amy recalled now. She told him, “I don’t know if you remember,” but there was one in particular when he’d come home, smelling awful and without a present.

Jim remembered.

There are different ways to deal with a destructive personality. Beth, who struggled with her own addictions, dropped out of high school and, for a time, cut her father out of her life. His colleagues at the paper either didn’t notice his drinking, or pretended not to. Amy took a third option. At the hearing, she looked him in the eye and delivered a clear message.

“I told him I loved him,” Amy said. “I would always love him. But he needed to get this help.”

It took a certain kind of toughness to confront her father in court, and 26 years later, Sen. Amy Klobuchar is pitching herself to America as a teller of hard truths. She has charted a path to the White House that goes through (not around) certain hard-luck swaths of Middle America now known as Trump Country but which used to be Democrat Country, and which still is Klobuchar Country. Places like the 8th Congressional District in Northern Minnesota, which saw one of the biggest swings in the country, from President Barack Obama to President Trump, but which continued to support Amy, as well.

It was an inheritance, politically speaking. Jim Klobuchar was from those parts, forged in the Iron Range, a region of miners, hard drinkers and isolated communities tied together by union organizing. He built his career as a champion of the forgotten workers, the likes of whom he knew growing up. He remembered them in his writing, even as he forgot his daughter’s birthday.

That wasn’t all Amy inherited from her father. Friends of Jim’s say they see a lot of him in Amy: the populist streak, the humor, and yes, the reports of a fierce temper. Intentionally or not, being the daughter of an alcoholic has become central to Amy’s presidential run. She brought him up during her star turn at a Brett M. Kavanaugh Supreme Court confirmation hearing, where she interrogated the beer-loving judge while appearing deeply unimpressed with his anger and self-pity. And last week, she announced a plan to combat addiction, making it an early campaign priority.

There are Democrats who believe winning in 2020 will have more to do with exciting turnout in cities than recovering voters from the industrial Midwest, and that Klobuchar’s campaign has more to do with a fading memory of America than its future.

Amy is selling herself as a candidate who can get things done: Under Trump, she’s been the lead Democrat on 34 bills signed into law in the 115th Congress, even if they weren’t front page news. But it’s possible voters may confront Amy with a hard truth of their own: That her brand of old-school Democratic pragmatism — with its focus on infrastructure, bipartisanship, and tamping down expectations of progressive policy dreams like Medicare-for-all or the Green New Deal — is not the kind of help that America wants. Or at least not from her.

Still, Amy is running for president as her father’s daughter, and she’s betting that what the country needs right now is not a revolution, but an intervention. As with any intervention, the trick will be getting people to listen.

There was a reason Jim Klobuchar’s divorce, his drunken-driving arrest and his relationship with his daughter were worthy of headlines in the newspaper.

He wasn’t just a journalist; he was a local legend, an unelected representative with a constituency and an origin story that affirmed both American progress and nostalgia.

He’d grown up in the town of Ely, the son of an iron ore miner, who saved up enough money to help his son get an education and a job aboveground.

When Jim used to drive Amy to visit her grandmother, the closer he got to the Iron Range the louder he would seem to talk.

“I’d ask him why he was yelling,” she said. “And he’d say, I’M. NOT. YELLING. THIS. IS. HOW. WE. TALK.”

It could be a volatile place, but people from there were proud of their home, which supplied the iron used to build the country. Jim moved away, first to the University of Minnesota and eventually to a job in the Minneapolis office of the Associated Press, where his connection to the Range offered him his first big break. It was 1960, returns from what would be the closest presidential election in nearly a half-century were still trickling in when Jim’s editor let him know whoever won Northern Minnesota would win the whole danged thing. That’s when Jim told him it was over, and wrote the first story declaring JFK the next president.

Voting against Republicans was basically a “law of nature” in the Iron Range, he’d write later.

By the time Jim was a celebrity journalist in Minneapolis, he was struggling to stay connected to his new life, and the divorce meant he would be around his young family even less.

Still, Amy’s sister, Beth, inherited her father’s demons; she drank and dropped out of school, and changed her name to Meagan. Eventually Meagan, who did not respond to interview requests, got her GED, stopped speaking regularly with her father and moved away — first to Iowa and then Florida, where, according to Amy, she’s doing better and works as an accountant.

Amy, meanwhile, stayed as close to her father as she could. She tried her best to fix him, for his sake, and for her own. She wanted, she said, her “family to be this perfect family.” And while that proved impossible, she could at least try to be the perfect daughter.

She’d drink occasionally, still does (though after the Kavanaugh hearing she avoided drinking beer in public until after her reelection).

“I’ve been careful my whole life because I didn’t want to turn into an alcoholic,” she said.

She was the rule-follower, the overachiever, the validation-seeker. “She always wanted his approval,” said Amy Scherber, one of her closest friends since grade school. “It meant a lot to her.”

It was why she didn’t hesitate to join Jim on his many biking adventures, even if she risked cringeworthy headlines about their relationship. Jim was a drinker, but he was no layabout; he would climb mountains, bike around the Great Lakes, jump out of airplanes. He liked the rush of an adventure, of setting a goal and accomplishing it.

It made for great newspaper copy, of course. At the bottom of it all, Jim was a storyteller; to be close to him was to become a character in that story. And Amy wanted to be someone worth writing about.

As the daughter of a newsman, Amy understands how to choreograph a story.

For my visit, she had planned a tour that would include a visit to her cozy townhouse with its creaky wood floors from the late 1800s (she proudly pointed out the cops had recently shut down a meth house in the neighborhood), a breakfast down the block (where she was greeted by neighbors and supporters), a visit to her old elementary school (where she recounted favorite anecdotes like the time she was sent home for wearing pants), and finally a look at her old house, where she had recently returned for a difficult visit with her father.

She’s been around journalists all her life, and has a way of keeping the conversation light and fun, like a slightly self-deprecating version of “A Prairie Home Companion” (“I had the second worst throwing arm in the fourth grade,” she said in the parking lot of her elementary school. “The worst was Gretchen Johnson.”)

Several former members of Amy’s staff say the lightness belies a deep preoccupation with her media coverage. Her team would start each morning with a phone call to go over articles that mentioned her by name, according to a former staffer. “Before the meeting began,” he said, “she already knew every story she’d been in.”

She’s now more famous than Jim ever was, and yet she finds herself struggling to get attention among a pack of Democrats 20-deep, some of whom, like former vice president Joe Biden, are making a similar “electability” pitch in places like the Rust Belt. And when she does get press, it’s not always positive.

There’s been tough coverage of her eight-year stint as a chief prosecutor for Minnesota’s most populous county, where she declined to bring charges in more than two dozen cases in which people, many of them black, were killed in encounters with the police.

But perhaps even more defining have been the slew of stories alleging Amy treats her staff poorly: including reports of beratings in the office, office supplies thrown at underlings, and attempts to sabotage future employment for those trying to leave.

Amy disputes those characterizations and friends say they were shocked by these accounts, that they’ve never seen that side of her. But those who knew Jim way back when are less surprised.

“To some degree you read the stories about Amy and her staff, and I said, ‘Yeah, well, she’s a Ranger, at least at heart,’ ” said Gary Eichten, a friend of Jim’s.

“He could be a wild man at times, particularly when he got on the phone with somebody he didn’t like,” Barbara Flanagan, Jim’s colleague, said in a 1995 Star article announcing Jim’s retirement.

Amy knew this about her father. Jim was the kind of guy who would yell at a gas pump if it wasn’t working, she said. He might blow up at a motel operator if asked to pay with a credit card when he wanted to pay in cash.

Her solution to the coverage of her own temper has been to turn those stories into an exercise in political branding. Amy has explained that she simply has high standards. And to enforce those standards she has an “Iron Range style,” a “blunt, direct and tell-you-what-I-think” way of communicating that at least some voters ought to appreciate.

“They want you to come out there, look them in the eye, and tell them the truth,” said Amy, who in 2007 became the first female senator elected in Minnesota. “I don’t think Trump was telling them the truth about everything, but they felt that way. And I understand why they voted the way they did, because they felt kicked around.”

When Amy announced her candidacy for president in February from an island in the middle of the Mississippi River, she stood onstage with her husband and daughter. Jim sat in the first row with snow dusting his overcoat and Minnesota Twins hat. He was 90 then, 91 now, with a thin gray mustache, and creases around his eyes that look more pronounced when he smiles, which he did, despite the 17-degree temperature.

“When I said that elected leaders should go not just where it’s comfortable but also where it’s uncomfortable, this is what I meant,” Amy said, her laugh cutting through the fog of her breath.

It was an unforgettable day, for Amy. But when one of his friends asked Jim about it later, he couldn’t remember.

A few years ago, Jim’s memory started going blurry. It was slow at first, though he likely knew what was happening. He’d seen it with his own mother who, late in her own life, suffered from Alzheimer’s; it was as much of an inheritance as the cash he’d found stuffed in coffee cans when Jim moved her into a home. That move was a struggle, for her, because she didn’t want to move, and for him because he knew she had to. Jim gave a speech about aging and memory loss back then. It was called: “I’m 70, my mother is 91, which one needs comforting.”

Jim didn’t want to move into a home either, when it came time a few years ago. And in moving him, Amy also found money, this time stashed in a backpack.

“It was a whole thing passed on,” Amy said. “I am not hiding money away anywhere. We lost that part.”

She doesn’t like to talk about her father’s battle with memory loss, initially having her staff ask that it not be discussed. It’s a topic that Jim never dealt with publicly, she said, explaining why. A few years ago, Amy asked him if he would write about it, but he demurred. With decades of newspaper stories, and 23 books, Jim had put a lot of himself out there, including what was often an ugly battle with addiction.

That was a battle, however, he was able to win.

Twenty-five years after Amy’s, and the court’s, intervention, and Jim is still sober. He found God, or in his words, was “pursued by grace.” He doesn’t go to Alcoholics Anonymous anymore, but that’s only because they come to him. Friends of Jim say he still looks like he could climb a mountain, and that there are certain stories he holds onto: about taking his father up in an airplane to see the Iron Range, the land he used to work beneath from up above; about the Minnesota Vikings; and about Amy.

“He still remembers a lot of things,” Amy said. “He can sing weird Slovenian drinking songs.”

He was always incredibly proud of Amy. He still is today, even if he doesn’t always remember she’s running for president.

“I help him to remember that,” said Mark Hanson, Jim’s pastor and friend of 40 years. Hanson was there at the intervention, and now he’s there most weeks, pulling clips that mention Amy and reading them aloud in Jim’s apartment.

“One of his phrases is, ‘Amy’s going to go a long way,’ ” Hanson said.

He could be right. Jim does, after all, have a history of predicting the outcome of elections before anyone else. But a lot has changed since then. The Iron Range is no sure thing for Democrats. Jim once called it a “microcosm” of America, but in a country that gets more diverse every year, that’s less and less true. Pragmatism, bipartisanship and building bridges may not be the most sought-after qualities for Democrats in a time of crisis. In a lot of ways, the country from Jim’s past can feel like a distant recollection.

On a recent visit home, Amy brought Jim by the house she grew up in, the one, for a time that he lived in, too. Decades later it was still structurally the same, same garage door, and windows that Amy and Beth used to peer out of in search of their dad. But the new owners had made changes, too: they’d painted the exterior a dark gray with an orange trim around the door, fenced in a basketball hoop along its side, planted a row of trees to demarcate the property.

When they pulled into the driveway, Jim cried.

“I just think it was hard for him to see,” Amy said.

Jim’s memories of this home were never perfect, but now, with all that had changed, he could barely recognize the place anymore.