(4-22-19) Housing First, the practice of offering individuals shelter regardless of whether they are stable or sober, was the subject of a recent Washington Post story headlined: D.C. housed the homeless in upscale apartment. It hasn’t gone as planned.

“The SWAT team, the overdose, the complaints of pot smoke in the air and feces in the stairwell – it would be hard to pinpoint a moment when things took a turn for the worse at Sedgwick Gardens, a stately apartment building in Northwest Washington,” reporter Peter Jamison wrote.

He explained that half of the building’s 140 units had been rented to previously “homeless men and women who came directly from shelters or the streets, some still struggling with severe behavioral problems…a high-stakes social experiment that so far has left few of its subjects happy.”

Last year, there were 121 calls to the police, up from 34, in 2016, although only five of those involved an arrest. The most disturbing incident involved a tenant throwing objects around inside his apartment. When the police showed up, the warned them that he had a shotgun and would shoot if they tried to enter. The standoff ended after several hours without any gun being found. The tenant was released only to be arrest two days later after striking another tenant in the head with a flashlight.

Judging a situation solely from reading a news account always is risky, but from what I read, this was not Housing First as it was intended.

First, it appears that officials did a poor job of choosing tenants. Several weren’t ready for the independence and responsibilities of living by themselves, a fact that the article noted.

Second, tenants in the building were not as welcoming as they should have been. Why was this? Were steps taken to educate and inform them before individuals were “dumped,” again as the article put it, into their building?

Joseph A. Bundy, 69, said he was smoking outside one day when another resident approached him: “This lady came up and said, ‘Don’t you know there’s a park up the street?’ I said, ‘What you talking about, a park up the street? My home’s right here.'”

Because the newcomers were using vouchers to pay their rents, they were clustered into small, basement units, largely segregated from others. Soon, they were known as the basement dwellers, liken to: ” ‘The People Under the Stairs,’ a 1991 kitsch horror movie in which a well-to-do couple live above a cellar filled with mistreated children,” according to the article.

But the main reason for my quibbling is because Housing First requires much, much more than simply offering someone a roof over their heads. It involves wrap-around services. It involves social connectivity. It involves giving people HOPE.

Typically, Housing First is paired with Assertive Community Treatment teams. These are teams of professionals – a psychiatrist or therapist, a peer support specialist, a living coach, a nurse – some multi-discipline approach of caregivers who provide services that address individual needs.

Many Housing First programs require tenants to pay 30% of their income in rent because that gives them a sense of responsibility and pride. They also require a tenant to meet at least monthly with an ACT team. Those visits often are when true recovery can begin because a tenant has consistent support and social connectivity with the team.

Someone actually cares.

Sadly, I have recently seen a rash of stories that question the value of Housing First. I’ve also heard rumors that some in the federal housing programs believe Housing First rewards bad behavior. That’s punitive and just plain wrong.

One of the finest examples of Housing First is the Lamp Community in Los Angeles. When I visited with the Corporation for Supportive Housing, I was told that 80% of tenants moved off the street and ended up successfully living independently.

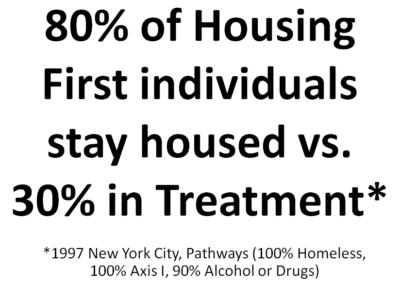

80% That is incredible! It’s also consistent to what was found in New York when Housing and treatment were combined.

The Lamp Community was profiled in Steve Lopez’s book and feature film, The Soloist. Here’s how it is described.

The Lamp Community was profiled in Steve Lopez’s book and feature film, The Soloist. Here’s how it is described.

A pioneer of permanent supportive housing in the United States, Lamp Community was founded on the conviction that homeless people living with a severe mental illness are more likely to succeed in treatment, and in all areas of their lives, when they have a stable home. The organization started as a drop-in center in downtown Los Angeles — which has more people living on its streets than New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco combined — and grew along with the city’s homeless epidemic, developing and implementing programs to provide clients with housing, health care, and drug and alcohol recovery services. Today, Lamp Community operates seven sites in downtown L.A.; maintains almost two hundred private, furnished apartments with access to clinical and support services; and assists more than 1,100 people each year, some of whom have been living on the streets for more than a decade.

When Housing First is done right, it works.

When it isn’t, everyone loses.