(3-18-19) Reader comments and questions.

Dear Pete: Your photo essay on the state hospital in Georgia was well done and thoughtful. However, the dubious distinction of largest of its type actually goes to a facility that was near my home town in New York – according to Wikipedia. See below.

Pilgrim Psychiatric Center, formerly known as Pilgrim State Hospital, is a state-run psychiatric hospital located in Brentwood, New York. At the time it opened, it was the largest hospital of any kind in the world. At its peak in 1954 it had 13,875 patients. Its size has never been exceeded by any other facility, though it’s now far smaller than it once was. “Pilgrim Psychiatric Center”.

We were also told, if we misbehaved as children that we would go to Pilgrim State.

My reply: My information also came from Wikipedia, which noted that Georgia’s Central State Hospital’s rival was Pilgrim State Hospital. I should’ve cited that too! Here’s that Wikipedia reference:

Central State Hospital. By the 1960s the facility had grown into the largest mental hospital in the world (contending with Pilgrim Psychiatric Center in New York).

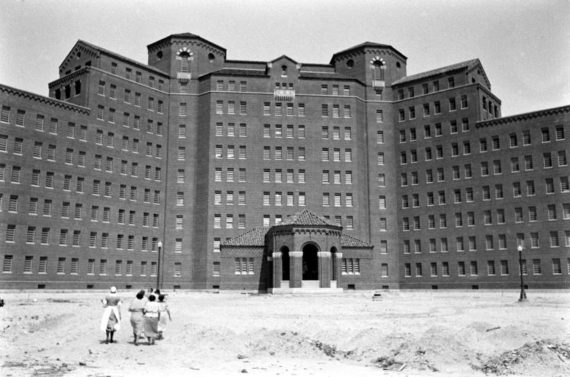

Pilgrim Psychiatric Center cir 1938.

Dear Pete:

You shouldn’t be posting a blog about the horrors committed at state mental hospitals at a time when we have a national shortage of beds and need safe, secure, and humane hospitals. Focusing on the past simply gives fodder to the anti-psychiatry fringe.

My reply: I was giving a speech in Milledgeville, Georgia, and wanted to see the now largely abandoned former hospital. The same week that I posted my photo essay, I featured a blog by a Virginia father, who credited the three years his son spent in a Virginia state hospital for his stability. From that blog:

The long term and quality treatment that our son received made a positive and transformative difference in his life and in ours.

In 2015, I posted a blog about an article published in the American Medical Association written by Dr. Ezekiel J. Emanuel entitled: Improving Long-term Psychiatric Care: Bring Back the Asylum.

“…The original meaning of psychiatric ‘asylum’ – (was) a protected place where safety, sanctuary, and long term care for the mentally ill would be provided. It is time to build them –again. At the moment, prisons appear to offer the default option and an inexpensive solution for housing and treating the mentally ill.

…A better option for a person with serious mental illness is assisted treatment in the community…However, comprehensive, accessible, and fully integrated community mental health care continues to be an unmet promise.

…At best, community treatment can provide high-functioning mentally ill persons a foundation for recovery. At worst, severely mentally ill persons drawing Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income risk becoming “commodities” in a profit-driven conglomeration of boarding houses reminiscent of the private madhouses of 18th century England.

Even well-designed community-based programs are often inadequate for a segment of patients who have been deinstitutionalized. For severely and chronically mentally ill persons, the optimal option is long-term care in a psychiatric hospital, which is costly…The annual rate at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital — a forensic psychiatric hospital in the District of Columbia– averages about $328,000 per patient annually.

The article is representative of what I believe is a return to thinking that modern day asylums are needed and are certainly preferable to letting persons die on our streets or end up locked in our jails and prisons.

Can everyone live in a community setting – especially with such services as Housing First , Assertive Community Treatment and Assisted Outpatient Treatment?

This is difficult to answer because community mental health systems are so badly funded and staffed that it is impossible for us to determine if this admirable goal is achievable. Which raises another question: If we don’t adequately fund community based services, what are the chances of us adequately funding modern state hospitals?

In Virginia, stays in hospitals average three days, unless an individual is so sick they are committed to a state hospital where the average length of stay is 21 to 30 days. That is not nearly long enough for some to become stable. In the father’s blog mentioned above, it took Andrew three years.

What I found in Georgia also has become typical. Most state hospitals currently focus almost exclusively on forensic patients and many of them are not there for treatment, but rather for competency restoration. Another troubling statistic. The average wait time for a non-life threatening illness in a hospital emergency room is three to four hours. For a psychiatric issue the wait is three days because of a lack of treatment beds.

Clearly, we need more beds. Should they be in state hospitals, crisis care units, or in local community treatment facilities? I hope my blogs spur discussions and hopefully answers (on my Facebook page) because ignoring the past will blind us to what we must guard against in the future.

Dear Pete:

I read your blog about the Interdepartmental Serious Mental Illness Coordinating Committee and the recommendations that you and the other non-federal members issued last year. What’s happening with that group?

My reply:

ISMICC was established to make recommendations about how federal departments can better coordinate and administer mental health services for adults with a serious mental illness or children with a serious emotional disturbance. Congress appointed 14 non-federal members on ISMICC to assist and keep an eye on our federal partners. ( I am the parent designee.) The non-federal members issued our first report in December 2017. It contained 54 recommendations.

Unfortunately, since issuing our report, our participation in discussions between federal agencies about their problems, has been limited because of the Federal Advisory Committee Act. Put simply, federal employees can meet and discuss programs but if any non-federal members show up, FACA requires prior public notice and for all meetings to be aired publicly. The law was designed to prevent advisory committees from hiding what they are doing. In our case, we simply want to be in the weeds with federal officials as they discuss how to improve delivery of services. We represent people who are impacted by those services and, I believe, have much to offer from the bottom up. Because of what we have been told about FACA, we are not being able to participate as much as we’d like.

However, the non-federal members were recently able to improve the ISMICC process.

From the moment I was appointed to ISMICC, I complained because the Federal Bureau of Prisons was not required by Congress to participate in mental health discussions. Here’s a sample from a December 2018 blog.

A Justice Departmental study found that as high as 45 percent of all federal prisoners have a diagnosable mental illness. The Washington Post recently published a study by The Marshall Project that faulted the BOP’s treatment of inmates with mental illnesses. This troubling study is simply the most recent in a long string of exposes that have documented abuses and failures in the federal system.

How can the federal government work to improve mental health services nationally if it can’t clean up its own house?

I especially found the lack of BOP participation troubling because of two ISMICC recommendations, which I helped author:

4.6. Require universal screening for mental illnesses, substance use disorders, and other behavioral health needs of every person booked into jail.

4.7. Strictly limit or eliminate the use of solitary confinement, seclusion, restraint, or other forms of restrictive housing for people with SMI and SED.

The non-federal members wrote a letter to Bureau of Prisons Acting Director Hugh J. Hurwitz who agreed last month to assign a staff member to participate in ISMICC discussions.

That is a significant step.

Dear Pete

Will I see you at NatCon this year?

My reply:

The National Council For Behavioral Health heard enough from me last year when I made three presentations at NatCon 18. I won’t be attending this year but I would urge anyone who provides behavioral health services to attend NatCon Conference 2019 whose theme is “Together We Can Change Lives” being held March 25 to 27 in Nashville, Tenn. The national council always puts on one of the largest and best conferences in the US.

Here’s a one minute clip from last year’s opening ceremony.