First of its kind program in nation scheduled to open next year.

(7-31-17) Morgan first began acting out when he was two years old. His behavior only got worse as he aged. His parents were given a number of conflicting diagnoses. None good.

At one point, his parents hired a live-in young counselor, who Morgan liked, to help them deal with their son’s outbursts. Next came a Connecticut boarding school for students with a wide range of disruptive issues from anxiety to Asperger’s to bipolar disorder. Despite that school’s stellar reputation, Morgan stole a car at age fourteen and went on a joy ride. By the time he was sixteen, he had been kicked out of four schools. Desperate, his parents sent him to a residential treatment center in Utah for “troubled teens.”

That helped, but not for long.

Pressured by a friend at age sixteen, he attempted to rob a taxi driver in Manhattan. A year later, paranoid and delusional, he called the police and reported that he was being followed. When they ignored him, he gathered all of the trash where he was living, put it on his stove and started a fire, believing firefighters would come and rescue him.

He was arrested for arson. A judge sentenced Morgan to five years in a New York prison.

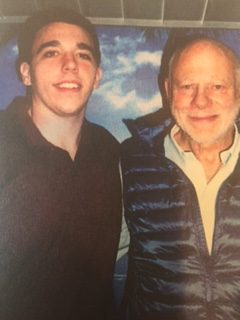

Morgan’s father, Francis J. Greenburger, pleaded with a prosecutor. With Morgan’s ten inch thick medical file in hand, Greenburger persuaded the prosecutor to give Morgan a break. He would be sent to a mental health treatment facility instead of Riker’s Island if his father could find a locked, treatment facility where he could serve his sentence.

Morgan’s father wasn’t some ordinary Joe. A high school drop out at age fifteen, Francis Greenburger was a self-made, multi-millionaire who oversaw more than 25-million-square-feet of prime real estate in Manhattan, nationally and internationally. He also owned one of New York’s most respected literary agencies. (An agent associated with his firm represented my first three books.) With his wealth, his social influence, his grit and his loving determination to help his son, Greenburger began his search.

Greenburger later told me, the prosecutor had “sent me on a fool’s errand. None existed.”

Despite Morgan’s well documented history of mental illness, Greenburger watched his son taken away in handcuffs and leg shackles bound for Riker’s Island, a notorious facility where few with mental illnesses emerge in better condition from when they entered.

For a loving dad such as Greenburger that was unacceptable. If he couldn’t help his son, he would help others. If there was no alternative to prison, he would build one.

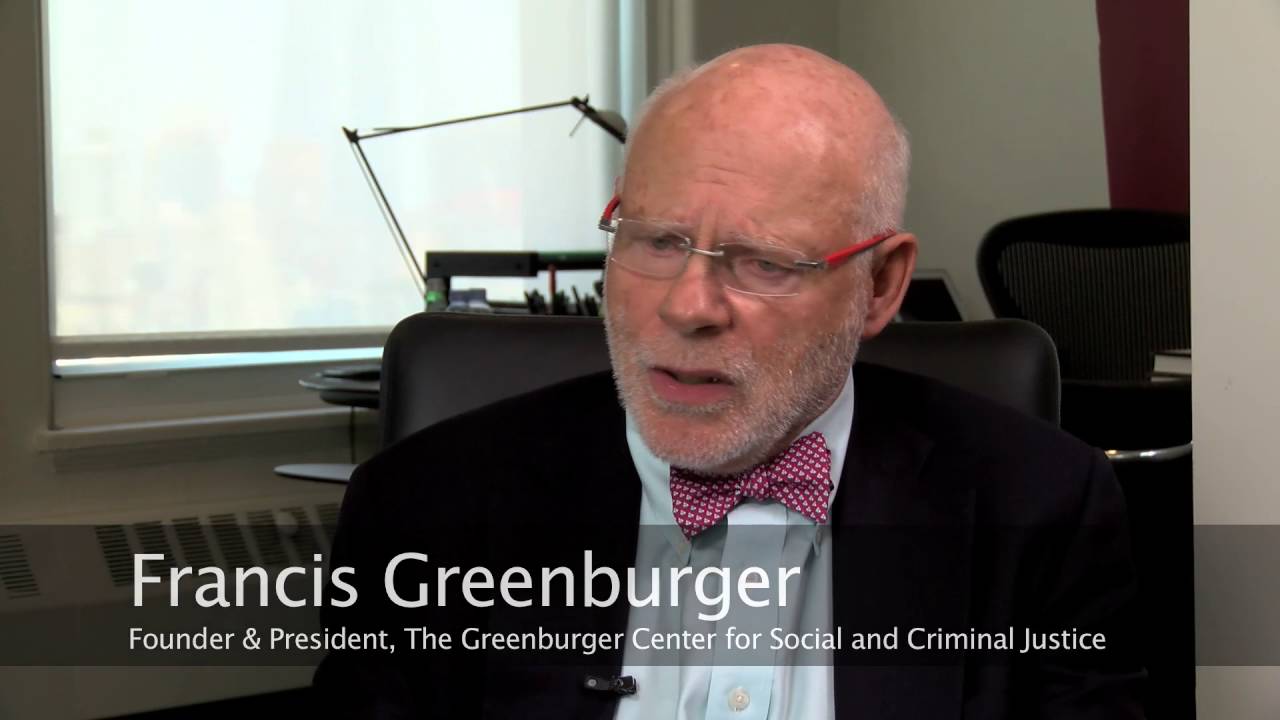

After consulting attorneys, mental health experts, and judges, he used his own money to create the Greenburger Center for Social and Criminal Justice.

Its first major project will be the opening of HOPE HOUSE on CROTONA PARK, an “Alternative to Incarceration” facility for individuals with serious mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders accused of certain felonies. Scheduled to welcome its first clients in late 2018, it reportedly will be the first facility of its kind in the nation, offering long-term residential and evidence based clinical programs for sixteen men and nine women.

“What does it say about our system that we incarcerate people for being mentally ill rather than try to find some other treatment modality?” Greenburger recently told the Wall Street Journal, part of his one-man educational campaign to call attention to deficiencies in our system. If you talk to most Americans, he explained, they assume the court system is fair. What most people think is “if the courts find somebody guilty, the heck with them.” But as Greenburger learned, de-insitutionalization in the 1980s/90s decreased the number of hospital beds available for individuals with life impeding mental disorders who need longer term help.

During lunch in Manhattan, Greenburger explained to me how Hope House will work.

A HEALING STOP BETWEEN THE COURTS AND PRISON

Entering the program will be completely voluntary with advice from a defendant’s lawyer and consent from both the district attorney and presiding judge. The accused agrees to a plea arrangement (pleads guilty) to a specific charge with the understanding that the sentencing on the charge will be “adjourned” (delayed) until he/she finishes the mandated Hope House treatment program.

Basically, if the defendant completes the treatment successfully he/she will serve no time in prison, although the defendant most likely would be subject to some sort of post release supervision.

Once at the house, residents will participate in evidence-based, work ordered day programming, mindfulness and mediation, violence reduction and restorative justice programs, and job/education services. They will receive trauma counseling; psychiatric and nursing care; medication management for psychiatric conditions as required; and cognitive and dialectical behavioral therapy where necessary.

In short, they will receive treatment rather than being brutalized and abandoned in jails and prisons.

They will not spend any longer at Hope House than they would if sentenced to prison but there is an opportunity for them to be released earlier than their original sentence would require if they successfully complete the Hope House program.

Greenburger has developed the Hope House concept and philosophy with help from Cheryl Roberts, an attorney and former judge who serves as executive director of the Greenburger Center. Re-entry planning will begin the moment a client enters the program, she said. The first goal will be stabilization of any substance use disorders, management of psychiatric symptoms and the treatment of underlying mental and physical diseases.

Next comes helping clients learn life and job skills that are essential to successful re-entry. At the start of the second year of a client’s stay, a re-entry coordinator will work with clients and nonprofit organizations to provide support in three major areas: 1. evaluation, motivational counseling, referral to residential programs; 2. family education, support, and reconciliation services; and 3. re-entry/recovery support and case management services.

Greenburger told me that there are no stand alone, secure facilities for accused felons in New York because defendants, who plead guilty, usually are immediately turned over to the Department of Corrections for incarceration.

Greenburger found a way to re-direct that path by having a judge impose an unsecured surety bond on the accused. Under New York law, a bail bond agent has the authority to revoke a bond and return someone directly to jail or the court. By employing a bail bonding agent at Hope House, Greenburger is able to keep the Department of Corrections at bay while legally diverting a state prisoner into a non-state funded detention/treatment facility – something he was unable to do for his own son, Morgan.

In addition to creating the Greenburger Center for Social and Criminal Justice and designing and raising funds for Hope House, Greenburger put aside time to write a book: RISK GAME: Self-Portrait of an Entrepreneur, that chronicles his rise-to-riches career, as well, as candidly describes his struggles to help his son.

Going Public And Understanding Limitations

Wealthy New Yorkers rarely talk about problems their children face, especially if their child has a serious mental illness. Stigma and embarrassment keep them mum. It’s a fact that Greenburger addresses in his engaging book.

Visiting my son in Rikers Island opened my eyes to a world that most people like me never see. Indeed, I could stop cocktail party chatter dead in its tracks by truthfully answering the classic small talk question, “And which college is your oldest son at?” All it took was one trip to Rikers to understand the inherent racial bias and detrimental effect on families of our criminal justice system. As I continued to navigate the system by visiting Morgan, working on his case, and researching alternatives for mentally ill persons who have broken the law, I became so disturbed by my discovery I was compelled to do something about it.”

Greenburger’s description of the rude and condescending treatment he received from correctional officers when he visited Morgan at Riker’s Island is a powerful testament to the dehumanization that both inmates and their families too-often face in prison settings.

But it is his journey to understand his son and his role as a father that I found most compelling in his writing and during our lunch together. Some are some pearls.

I had weathered economic problems that almost brought me to the edge of bankruptcy, the drowning of my first son, my wife, Judy’s cancer and eventual death. And yes, I was banged up from all of it. But I was also stronger in my ability to temper my hope and my disappointments to maintain a clear vision of what I wanted to do…

I often replayed the moment, days after Morgan’s birth and adoption, when I stood before a Florida judge and swore to be a faithful father to Morgan for better or worse. I would always do my very best to be true to that vow. Morgan had no other champion apart from me…

I had decided long ago that my job was not to be Morgan’s judge and jury but his advocate. Still, for the sake of my own mental health, I tried to follow (a friend’s advice) and distance myself from the role of Morgan’s savior. He was no longer a little boy that I could watch while he rode out a tantrum…

After fighting for such a long time and in every way possible to help Morgan, it made me sad that I hadn’t been more successful. In the end, I couldn’t feel sorry for myself, but I could feel sorry for him. Because really, what could be more challenging than being him?

After serving his sentence, Morgan was recently released from prison.