(7-26-17) A grinning Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe was able to bluff his way through a recent appearance held in Washington D.C. when questioned about his decision to execute an inmate with a serious mental illness. While claiming, once again, that he personally opposed the death penalty, he rationalized the execution by assuming the role of a modern day Pontius Pilate and repeating damaging testimony offered by a psychiatrist at William Morva’s first trial while dismissing testimony later by an independent psychiatrist and new evidence about Morva’s mental health history. I’m thrilled that a former prosecutor and defense attorney rebuffed McAuliffe in this Washington Post opinion piece posted Sunday, July 23rd.)

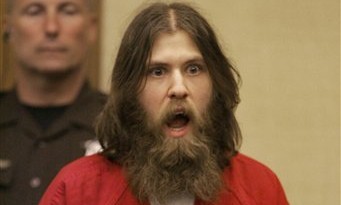

Photo by Roanoke Times

Gov. McAuliffe made an irreversible mistake

By Gene Rossi and Edward J. Ungvarsky. first published in The Washington Post.

When the governor refused to intervene, he missed a chance to exercise a solemn constitutional duty to save Morva’s life. In a case that cried out for mercy, McAuliffe disregarded that the sentencing jurors never heard the compelling evidence of Morva’s long-standing, debilitating mental illness. Although Morva’s death is an irreversible mistake, he should not die in vain.

Death should be an extraordinary, rare punishment. U.S. and Virginia laws reflect the centuries-old bedrock principles that a death sentence is exceptional and that mercy alone is always reason enough to avoid the death penalty.

Jurors are not only allowed but also required to follow their individual moral judgment in determining whether death is the appropriate punishment. The governor, in wielding his awesome power to grant or deny clemency, carries that same obligation. Virginia’s constitution provides the governor the unrestricted power to commute capital punishment to life in prison.

This psychiatrist could have related to jurors what scores of Morva’s family members and friends reported to her: They had watched Morva’s mental health precipitously decline in the years before the crimes and had seen his untreated illness worsen for the remainder of his life. Morva’s mother and others reported how, for years, he refused to take visits or calls from her and his lawyers, believing them all to be part of the grand conspiracy. Jurors also did not hear that Morva believed his behavior was saving Native American tribes, nor that he subsisted on a diet of raw meat and pine cones while living in the woods barefoot in the winter. The experts at Morva’s trial never learned, or bothered to learn, about Morva’s debilitating delusions.

Instead, jurors heard only that Morva’s “odd beliefs” resulted from a personality disorder that the prosecution asserted was untreatable and made him likely to kill again. Given the sparse, inaccurate information before them, the jurors unsurprisingly sentenced Morva to die.

The details of Morva’s debilitating illness from his family, friends and psychiatrist would have been powerful evidence — had the jurors ever heard it.

Faced with this new and clearly relevant evidence, the state chose to ignore it, never seeking an expert to consider what witnesses said and to review the psychiatrist’s findings.

Oddly, the governor’s statement denying clemency relied on the fact that the psychiatrist’s post-trial diagnosis conflicted with the testimony jurors heard at trial. But that is precisely the point: Jurors never heard the observations of severe symptoms that anyone who crossed Morva’s path in the years before the crime would have seen and the informed opinion of a qualified doctor. Rather, the experts at trial relied on outdated information about Morva’s childhood long before his symptoms began.

In denying clemency, the governor asked, “Does Morva deserve to live?”Instead, he should have asked, “Do I, in my personal moral judgment, think the state proved it has the right to take this life?” The right question would have led McAuliffe to reach a different conclusion and to spare Morva’s life.

Applying mercy to capital cases reaffirms our common beliefs in the rule of law and in the dignity and value of every person regardless of what he or she has done.

Gene Rossi is a retired Justice Department prosecutor. Edward J. Ungvarsky is a career public defender based in Vienna who represents defendants prosecuted in Virginia on capital murder charges.