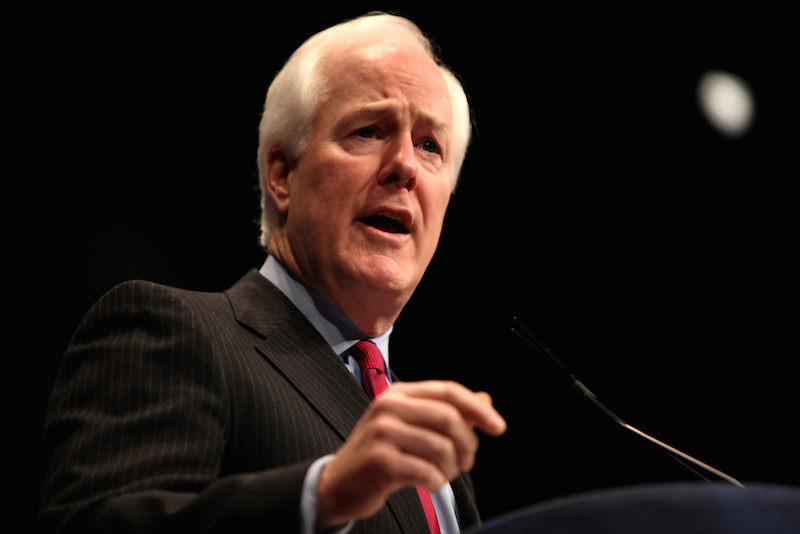

Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, the powerful Senate Majority Whip, is making passage of Mental Health Reform Act, his top priority in upcoming lame duck session.

(10-3-16) I’m hearing the Senate may still pass the Mental Health Reform Act (S.2680) in November when Congress returns for a lame duck session, but only if several new obstacles can be overcome.

The bill is the Senate’s version of Republican Pennsylvania Rep. Tim Murphy’s Helping Families In Mental Health Crisis Act and was initially introduced by Senators Chris Murphy (D. Conn.) and Bill Cassidy (R. La.) as S. 1945 but has been renumbered now that it is under the control of Sen. Alexander Lamar (R-Tenn.), the chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions.

You might recall that the Senate version ran into trouble when Senator John Cornyn (R-TX.) moved to merge his mental health bill into the Murphy-Cassidy bill. Senate Democrats, including Senators Charles Schumer (NY) and Harry Reid (NV.), took issue with parts of Cornyn’s bill that dealt with restoring gun ownership to veterans who the Veterans Administration had decided were incompetent to handle their own financial affairs. I’ve been assured that issue has been overcome.

However, now two new ones could kill the Senate version and both concern money.

The Senate bill that Lamar’s committee unanimously passed didn’t address the Medicaid Institutions for Mental Disease rule, more commonly known as the IMD exclusion, because changes in Medicaid fall under the preview of the Senate Finance Committee. That regulation prohibits federal funds from being paid to clinics with more than 16 beds that treat mental health and substance abuse patients. It was hustled through Congress during the deinstitutionalization movement to discourage the warehousing of persons in community settings and to shift the costs of caring for individuals from the federal government to the states. While there is a widespread feeling in both chambers that the IMD has outlived its usefulness, the cost of eliminating it entirely has been estimated to between $40 to $80 billion to Medicaid.

Before Congress went on break, the Democrats – led by Sen. Harry Reid – said they wanted to repeal the IMD exclusion but that was seen by many as a “poison pill” introduced to keep Republicans from bringing S. 2680 to the floor for a vote. Cynical Republicans grumbled that Reid didn’t want them taking credit before the November elections for passing major mental health reforms.

If Reid was playing politics, there’s a good chance that he will drop his efforts during a lame duck session to repeal the IMD exclusion, which Republicans would oppose because of the high price tag of eliminating it.

There are multiple ways the IMD could be reformed short of full repeal, Caitlin Owens explained earlier this year in a Morning Consult article. Congress could raise the limit on the number of beds, which would allow reimbursement for services at larger facilities. It could adjust the definition of a mental health disease, which would change the number of facilities deemed mental health facilities under the rule. It could change other parameters of the law, such as limiting the payment exclusion to long-term inpatient stays, as opposed to the current 15-day limit.

Murphy’s House bill addressed the IMD in a narrow way by proposing that Medicaid Managed Care Organizations be allowed to receive reimbursement for acute stays of up to 15 days per month in an IMD – which covers about 70% of Medicaid beneficiaries. Such a move would cost considerably less than full repeal.

So the question is — will Reid make an effort to eliminate the IMD after the elections (and effectively kill chances of a bill passing) or was his earlier move a red herring?

The other financial hurdle is an effort by Senators Roy Blunt (R. Mo.) and Debbie Stabenow (D. Mi.) to expand the Excellence in Mental Health Act that provides federal funding for community treatment. The original bill was signed into law in February 2013 to “put community mental health centers on an equal footing with other health centers by improving quality standards and fully-funding community services and offering patients increased services like 24-hour crisis psychiatric care, counseling and integrated services for mental illness.”

The bill was signed into law by President Obama in 2014 who declared it one of the most significant steps forward in community mental health funding in decades. It called for funding programs in eight states. President Obama later announced that there was enough money in his budget to pay for programs in 14 states. But Blunt and Stabenow are now pushing to expand the act to 24 states. That could cost about $1.5 billion, which some Republicans are saying is too much.

The Senate will return in mid-November for a lame duck session and Senator Cornyn, the powerful Senate Majority Whip, has said that getting S. 2680 passed is his top priority.

One way to guarantee the bill will be voted on and approved is for Reid to agree to drop his push for getting rid of the IMD and for Blunt and Stabenow to agree to scaling back the 24 state number to a lesser one. Or, the Blunt-Stabenow bill could be introduced on its own and not added to S. 2680. But that would most likely doom it because of Republican votes against it. The bill is being pushed by the National Council for Behavioral Health.

“This legislation is a critical step forward in making mental health and addiction care available to every American in need,” my friend, Linda Rosenberg, president and CEO of the National Council, was quoted on Sen. Stabenow’s webpage as saying. “The Expand Excellence in Mental Health Act will expand Americans’ access to lifesaving mental health and addiction care, while supporting providers with the resources to not only immediately help each individual who walks into a clinic, but to also coordinate their behavioral and physical health needs. Every state that is working to transform its care delivery system deserves to be able to do so. The National Council pledges to continue working with Senators Debbie Stabenow and Roy Blunt to ensure that all 24 states have the opportunity to implement Excellence Act resources.”

In an email to me, Linda added: “We will appreciate Congress passing a bill, but if the bill does not expand and strengthen treatment capacity, we will be back. Grants are not enough to address the disorders that account for the greatest burden of disease in our country.”

In addition to Reid’s effort to eliminate IMD and fussing over expanding the Mental Health Act, there is one other major piece of mental health legislation pending in the Senate.

It is Sen. Al Franken’s (D-Minn.) Comprehensive Justice and Mental Health Act, which would bolster mental health courts and crisis intervention teams, authorize investments in veterans treatment courts, and help state and local officials identify people with mental illnesses inside the criminal justice system. It also would focus on corrections-based mental health programs and provide for law enforcement training about how to respond to incidents involving someone with a mental health condition.

The only issue with Franken’s bill, which has widespread bipartisan support, is whether he will merge it into S. 2680 or risk trying to get it onto the Senate floor for passage on its own, which can be tricky. No one expects it to be opposed if Franken can get it to a vote during this testy Congress.

If the Senate can resolve its fighting over money for mental health and pass S. 2680, it would immediately be merged with Rep. Murphy’s House bill and sent to President Obama for signing before his term ends.

But that remains a big “if.”

If you want a mental health bill passed, now is an important time to let your Senators and House members know.