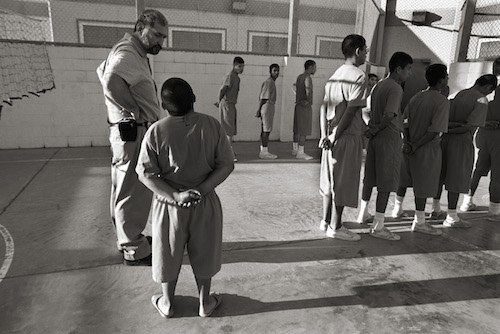

“Voices from Juvenile Detention: Kids Behind Bars”(see note at end of blog about this photo.)

(7-12-16) Authorities used to claim that a good way to straighten out a troubled youth was to put him in jail for a few days to scare him straight. But last night at a meeting about jail diversion, a Fairfax County, Virginia court services director said that putting a troubled juvenile in jail makes it ten times more likely that he will continue being caught up in the criminal justice system.

By contrast, Bob Bermingham Jr. said Fairfax County recently diverted 20 kids, who were considered low risk offenders, from being locked up into treatment services. Only one re-offended. Bermingham added that up to 60% of juveniles being held in detention centers have a mental illness.

Bermingham told an audience of about seventy attendees at a meeting of my local county’s Diversion First program that the juvenile court system by statute looks for ways to keep juveniles out of the criminal justice system because criminalizing them does more harm than good. Unfortunately, during the generally upbeat meeting it soon became clear that some Virginia elected officials simply don’t understand that this same principle applies when an offender is an adult with a mental illness or addiction problem.

More on that later, but first the good news.

Championed by Sheriff Stacey Kincaid and supported by Board of Supervisor Chair Sharon Bulova, Board Supervisor John Cook, and Fairfax Police Chief Edwin C. Roessler, the recently launched Diversion First program is beginning to have an impact.

From January to June, Fairfax law enforcement diverted 208 individuals with mental problems into treatment rather than arresting them. The county also continues to implement the Memphis model of Crisis Intervention Team training, having graduated an additional 170 police officers since September along with 18 dispatchers. In addition, 201 Sheriff’s deputies, 71 fire and rescue officers, and 23 juvenile intake officers have undergone Mental Health First Aid training. One hundred precent of court magistrates have completed Mental Health First Aid classes.

Supervisors Bulova and Cook have gotten $3.89 million from the county budget specifically for Diversion First, which has enabled the county to beef-up its staff at its recently opened Merrifield Crisis Response Center (drop off/triage center), which was opened as part of the Diversion First initiative.

Lyn Tomlinson, an assistant deputy director at the Fairfax-Falls Church Community Services Board announced that the first mental health professional an individual in crisis meets when brought into the center is a peer specialist. She added that the CSB has opened several “calming rooms” where individuals can be counseled without feeling threatened, as they might feel when taken to an emergency room or jail. She also reported that the county has set aside $500,000 for housing specifically for persons who are being diverted and the CSB is seeking another $700,000 from the state for additional housing for persons with mental illnesses and addictions.

Fairfax County Fire Chief Richie Bowers said firefighters and emergency responders were being trained at a rate of 75 to 100 per month, adding that emergency medical responders were delighted they could take residents who were psychotic to a crisis center rather than emergency rooms where they often were evaluated and then released (presumedly because they were not considered dangerous) only to be dialing 911 within a few hours.

While clearly pleased with the county’s progress, Laura Yager, the county’s de facto director of Diversion First, cautioned that the program still faces challenges when it comes to diverting adult offenders. Despite the success of a “veterans docket” that was launched by Circuit Court Judge Penny Azcarate, local court officials, as well as, the state judiciary and Virginia legislators continue to be skeptical of diverting adults after they have been arrested.

Despite overwhelming evidence from other states where mental health courts have been thriving for years, some legislators continue to mouth worries about prosecutors letting an offender off the hook because of a mental health diagnosis. This thinking is so prevalent that proponents of diversion cannot use terms such as “mental health courts” or “restorative justice,” but instead refer to courts as “specialized dockets” and restorative justice as “alternative accountability programs.”

What’s more worrisome than these ridiculous word dodges is apparent confusion about diversion, even among those elected leaders who are tasked with improving the state’s mental health services. Both Delegate Vivian Watts and Robert Bell, who are on a special commission studying Virginia’s mental health system, have questioned specialized dockets.

In states such as Pennsylvania, Ohio, and even Maryland, where mental health courts have been successful for years, such skepticism would be quickly proven unnecessary. One would hope that endorsements of diversion programs (that include mental health courts) by the federal government through SAMHSA, the National Stepping Up Initiative and most recently the White House might sway critics.

In 2009, I asked to meet with the then Chief Judge in Fairfax to discuss jail diversion. He refused to talk to me. Six years later, I first revealed on this blog that Natasha McKenna, a 37 year-old African American who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, had died after being repeatedly stunned with a Taser in the Fairfax Detention Center. Because of her death, Sheriff Kincaid and county officials launched Diversion First.

Ignorance and arrogance prevented the county from taking steps years earlier — steps that might have prevented her death, saved the county from being sued and soiled the reputation of the sheriff’s office.

It will be unfortunate if ignorance and arrogance again keeps Virginia from fully implementing jail diversion because of undo worries about specialized dockets.

From the photo above: “Voices from Juvenile Detention: Kids Behind Bars”(see note at end of blog.)

It sounds harmless: “pre-trial detention.” But the reality is far different. In a squat block building in Laredo, Texas—and in similar places around the nation—children await trial or placement in concrete cells while the underlying issues that led to their behavior fester. Some are addicts who need treatment; others are kids battling mental illnesses. This is the world of young felons, of kids gone astray, of children who cry for their mothers from behind bars. Some have skipped class too much, some have murdered in cold blood. At least half of the kids have been incarcerated before. And, if society’s attempts at rehabilitation ultimately fail–or if the parent can’t or simply won’t do anything to turn around years of neglect and abuse–just a few more visits to juvenile detention will harden some of these kids into full-fledged adult criminals.