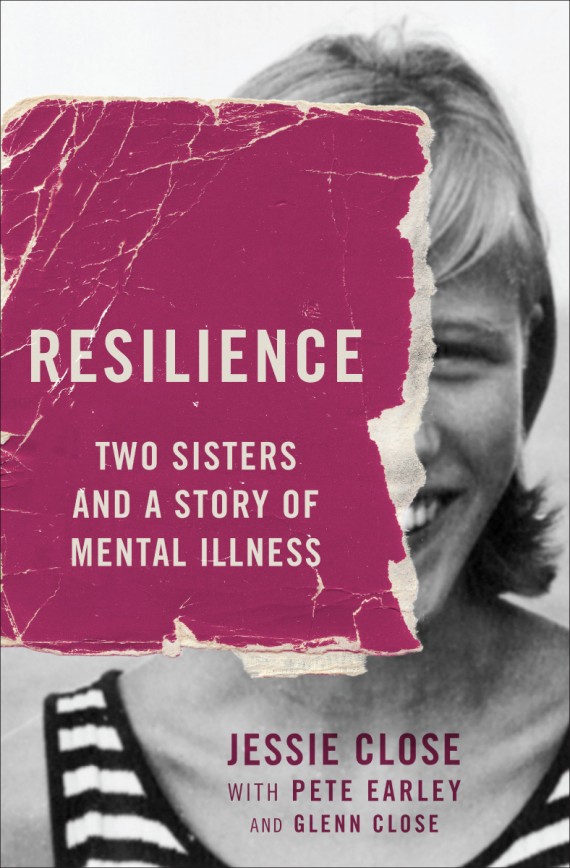

RESILIENCE: Two Sisters And A Story Of Mental Illness, the intimate memoir that I helped Jessie Close write is now available in paperback with a dramatic new cover!

It’s the brutally frank story about Jessie’s struggles with bipolar disorder and alcoholism, and her inspiring recovery. Her talented sister, Glenn Close, widely acclaimed as one of the finest and most versatile actresses in Hollywood, was instrumental in helping Jessie and her son, Calen, after he also was diagnosed. As most of you know, Glenn is a co-founder of the anti-stigma non-profit BringChange2Mind. As part of its campaign, it has produced two powerful Public Service Announcements for television. Glenn also generously wrote three personal vignettes for RESILIENCE which are included in both the hardback and just released paperback. She has graciously allowed me to reprint one of them. You can order the paperback edition of Jessie’s book here.

From RESILIENCE: Two Sisters and a Story of Mental Illness

By Jessie Close with Pete Earley and Glenn Close

Vignette Copyright by Glenn Close @2015 Used by permission

It’s strange how memory can distill something down to a single image and yet somehow that single image retains its power to invoke all the other senses. I realize now that my memory of my little sister, Jessie, when she was a child is a collection of images around which other sensations move in and out of my consciousness. Maybe that’s because, compared to most other families, our family has a shocking lack of pictures, especially throughout Jessie’s childhood and beyond. For the most part, at a certain point the pictures just stop. Hers is the only baby-picture book that remains painfully incomplete. Of course, Jessie was the fourth child, and our mother’s days were full of tending to three other kids, a herd of various pets, and a husband who came home from interning at Roosevelt Hospital in New York City only on weekends, if then. I treasure any pictures of us that were taken as we were growing up because they shine a light onto memories full of shadows. Without their validity and light—solid evidence surrounded by a solid frame—all is vague and mutable. So I will attempt to reconstruct a few memories of Jessie from images in my mind’s eye that I have carried with me all these years.

Jessie must have been about eighteen months old—a pale baby with patches of wispy blond hair and big blue eyes. I notice the blue veins in her temples. Mom is trying to feed her. For some reason this image is set in a tiny back room of Stone Cottage, our family’s first home. The walls of the room are painted a dark green, as it is our father’s study when he is home. There are shelves stocked with strange-looking medical instruments, including clamps and long, skinny metal tweezers. Could that be true? I don’t remember a desk. Had that room been turned into Jessie’s room?

Jess was always an extremely picky eater. Mom would spend hours trying every baby-seducing trick she could think of in an effort to get her to open her mouth. There is a little rhyme she would use in an attempt to throw Jessie off guard:

Knock, knock! (Mom gently knocks on Jessie’s forehead)

Peep in! (Mom pushes up Jessie’s eyebrow)

Lift the latch! (Mom gently pinches the end of Jessie’s nose)

Walk in! (Jessie’s cue to open her mouth)

Chin-choppa! Chin-choppa! Chin-choppa! (Mom moves Jessie’s chin up and down as if she were chewing)

Every now and then, the enthusiastic coaxing and funny faces would make Jessie laugh, and Mom had to be quick on the draw to get in a spoonful. Sometimes nothing worked, and Mom, exhausted, would have to declare a truce, defeated by the stubborn little person in the high chair. When she got older, Jessie went through a plain-spaghetti phase; later, red licorice seemed to be her sole sustenance. She was always a skinny little thing. She still isn’t that thrilled by food and has never had the desire to cook. When she does, it is usually with less than felicitous results.

Our lives changed after we moved from Stone Cottage to Hermitage Farm, on John Street in Greenwich. Our parents bought the farm from Granny Close after Granddad Close died. Granny herself moved into a tiny cottage next door, over a high stone wall. Our parents were getting more and more involved with Moral Re-Armament, so they weren’t around a lot. Meanwhile, Granny was determined that we get a religious education. Most Sundays we would straggle behind her up the bluestone path into the local Episcopal church, dreading Reverend Bailey’s boring sermons. The church was called St. Barnabas, so we called our Sunday travail the Barnabas and Bailey Circus. There are no images of our mother and father in that scene. Without them it was as if the center of our universe had fallen away and we were solitary planets with no gravitational pull to keep us from spinning away into chaos.

We eventually moved into a house on an estate called Dellwood, in northern Westchester. Dellwood had been donated to MRA by one of R. T. Vanderbilt’s granddaughters and was used as a center. In my memories Jessie is often nowhere to be seen. What was it about those sad days that my mind refuses to retain? Tina was twelve. I was ten. Sandy was eight, and Jessie was six. We weren’t abused. We always had clean clothes and good food and a solid roof over our heads.

I have always felt very solicitous of Jessie. She touched and amused me. She was funny and deeply original and had a wonderfully expressive face. I loved her quirky outlook on life. I used to tease her, knowing that her reactions would be dramatic and funny. Looking back, it seems horribly cruel, but at the time it was just big-sister razzing. Once, we were washing dishes after dinner in the kitchen at Dellwood. There was a window behind the sink, and the night had turned the window black. Jessie was drying dishes at my side, my happy helper. Suddenly I stiffened and stared into the darkness outside, widening my eyes and pretending to hyperventilate. Jessie froze. I moaned and then built up to a shout: “Oh, no…oh, no…oh, no-o-o!” Jessie started screaming and stamping her little feet, looking like she was running in place, whipped into hysteria in a split second.

Another time, I put a sheet over my head and slowly peered around the door into Jessie’s bathroom, where her nanny, Meta, was giving her a bath. Jessie was standing up in about three inches of water as the tub filled up. When she saw the ghostly sheet, she started screaming and stomping her feet. Water splashed all over the walls, not to mention all over Meta. I got yelled at, and Jessie eventually calmed down enough for a bedtime story. Needless to say, she was too young to think it was funny.

My most powerful image from that time in our lives: we are in the upstairs hall at Dellwood. I think it is daytime, but there is not much light in the hall. I am about eleven years old, so Jess must have been about five. She is standing in front of me in a summer dress. She has two long, blond, skinny braids that reach to below her waist. She is not looking at me, and yet even though I can’t see into her eyes I call tell that she is upset. With her right thumb and forefinger, she is violently rubbing the soft skin between her left thumb and forefinger. She has worried it for so long that it is red and crusty. Sometimes it bleeds. I can feel her distress. I pull her hands apart to try to make her stop. She pauses for a moment, looks up at me, and then starts rubbing again. I don’t understand why she keeps doing something that must cause her pain.

In my mind the scene has no conclusion. It is simply the two of us wordlessly facing each other in a somber hallway. I am intently focused on what my little sister is doing, not understanding why she is doing it and not being able to stop her. I know that outside there was a garden and a lawn gently sloping down to a shaded, grassy path leading into shimmering hay fields. Maybe our collie, , was trotting up from those fields at that very minute. Downstairs and out the front door of the house, across the driveway and up a set of stone steps, were a swimming pool and a set of swings. I’m not sure if there was a sandbox, but there was cool sand under the swings. Through the open, shaded windows in the bedrooms that opened into the hallway, we would have been able to hear the metallic, sawing sounds of cicadas in the high heat of the summer day. But all I see in my memory is a silently distraught little girl, my sister, standing alone in front of me, mutely intent on making herself bleed.