After Crazy: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness, was published, I wanted to write a book about homelessness. Georgetown Ministries in Washington D.C. allowed me to spend several weeks with one of its workers who patrolled the streets handing out water bottles and helping mostly homeless men who had mental illnesses and co-occurring addictions. I met a handful well enough to write what I thought was a fabulous book proposal.

But when my agent showed it to my editor, he rejected it, telling me that “No one wants to pay $30 for a book about those people.”

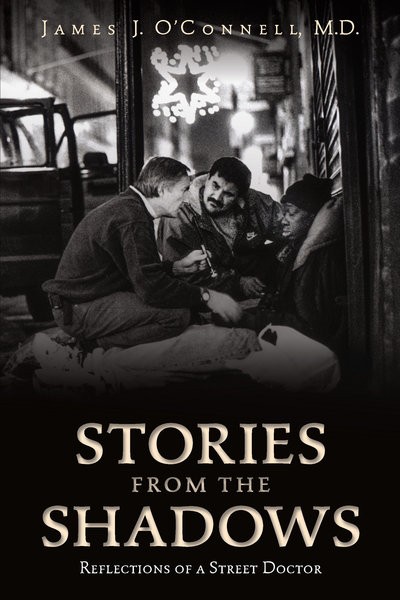

I’m glad that Dr. James J. O’Connell and the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program didn’t listen to my editor because Dr. O’Connell’s recently published book Stories From the Shadows: Reflections of a Street Doctor, is one that I wished I would have written. It is a gem and one of the best books about homeless Americans that has ever been written.

Stories From the Shadows is being marketed as a memoir, but it really isn’t. What Dr. O’Connell has assembled are 30 short stories online — some more diary entries than narrative tales — about men and women who have crossed paths with him since 1985 after he earned his M.D. at Harvard Medical School, completed his residency in internal medication at Massachusetts General Hospital and decided to spend a stint inside what then was New England’s largest and oldest shelter in Boston.

He intended to stay only a few months before moving to what surely would have been a rewarding and profitable career in oncology. He not only stayed working as a doctor on the streets, but two years later helped form the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program. Scores of homeless men and women in Boston are better because of it.

If you are searching for uplifting recovery stories where the downtrodden rise above the often unfair obstacles that they encounter, you will be disappointed. Many of the stories that Dr.O’ Connell tells are grim and end badly for those who come to him seeking help. But this is the brutal reality of life on the streets and it would have been a lie to window dress the obstacles and incredible sadness that Dr. O’Connell encounters day-after-day or to put a happy face on what is a national scandal and ongoing tragedy.

This is not to say that this 184 page book lacks hope and inspiration. It is filled with heroes, mostly Dr. O’Conner and the other caregivers who spend countless hours caring for people who most of us avoid when we see them curled in doorsteps for the night and sprawled on sidewalks. Dr. O’Connell and his coworkers clearly believe that every life, even the most damaged, has value and worth. It is in his incredible curiosity about people, his unflappable spirit and his passion for medicine, that we are able to see his patients as he sees them through lenses that reveal raw courage, individualism and resilience.

Dr. O’Connell was 37 years old by the time he became a doctor which was later than many. A child of the 1960s, he’d graduated from Notre Dame during the turbulent spring of the Kent State shootings, avoided Vietnam by earning a master’s degree in theology from Cambridge University in England, and then moved on to teaching and coaching in a Honolulu public school before returning to his hometown of Newport, Rhode Island to work as a waiter — all the while enjoying Socratic dinner discussions with friends, endless skiing on Madonna Mountain and long motorcycle rides as he quietly searched for some calling that would give his life purpose beyond simply having a good time.

On his first day at the Boston City Hospital shelter, a veteran, street savvy nurse named Barbara stripped him of his newly earned stethoscope and led him into an intake area which held ten chairs and buckets of warm water mixed with an antibacterial called Betadine. For the next two months, his job was to “learn the art and skill of soaking feet” which he discovered was performed not only for comfort and hygiene but also as a sign of service and respect to the street people who arrived each day often dirty and diseased. No medical questions, no diagnosing. Every homeless person was addressed by name.

“I thought you were supposed to be a doctor. What the hell are you doing soaking my feet?” one man asked.

Dumbfounded, Dr. O’Connell couldn’t think of anything better to say than, “I do whatever the nurses tell me to do.”

This vignette about washing feet and Dr. O’Connell’s self-effacing demeanor are insights into his humbleness and humanity. Slowly, with the passage of time, he gains the most belligerent and toughest clients trust and admiration, and he finds a life well worth living in serving others.

I will not spoil the book by describing some of the colorful characters that inhabit Dr. O’Connell sidewalks and alleyways. At some point, he felt compelled to record their stories because in doing so, he was giving their lives value that he felt had been overlooked when they wandered Boston’s streets. It is difficult to read this book without feeling outrage at the inhumane way we abandon and discount the sick and mentally ill among us. Yet, Dr. O’Connell never becomes dispirited. And that ultimately provides this collection its uplifting thread. In his sharing of the stories of others, we see a portrait of a caring doctor who practices his skills late at night in the worst and most threatening neighborhoods offering aid to individuals who, as one medical colleague put it, survive “lost in plain sight.”

I once heard a Jewish legend about 36 hidden “tsadikim” –righteous and just men on whom the world depends for its existence.

I’m don’t believe Dr. James J. O’Connell is Jewish, but if there are 36 especially godly men living among us, I suspect he is one of them.

Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air interviewed Dr. O’Connell this week and you can listen to it here.

You can purchase Stories From the Shadows here.

In addition to his work in Boston, Dr. O’Connell serves on the board of the Corporation for Supportive Housing which finds innovative ways to help communities reduce homelessness.