I have been a member of a mental health subcommittee studying ways to improve services in Fairfax County, Virginia where I live. The introduction to our draft report might be useful reading for many of you. I have edited out several local references and added some key points in parenthesis.

You’ll find that much of our report contains information that I have cited in my speeches and previous blogs. You might want to compare what we are suggesting with services in your community.

Mental Health Reform: An Introduction

“Police officers have increasingly become the first responders when a citizen is in the midst of a psychiatric crisis. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), up to 40% of adults who experience serious mental illness in their lifetime will come into contact with the police and the criminal justice system at some point in their lives. (1) The vast majority of these individuals will be charged with minor misdemeanor and low-level felony offenses that are a direct result of their psychiatric illnesses – the most common being trespassing or disorderly conduct.

Despite the minor nature of these crimes, encounters between persons with mental illness and the police can escalate, sometimes with tragic consequences. Nearly half of all fatal shootings by law enforcement locally and nationally involve persons with mental illnesses.

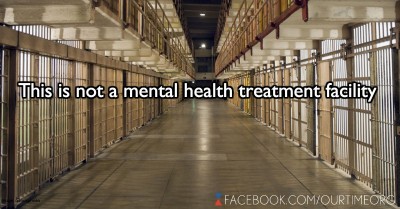

Jails and prisons have become the largest psychiatric facilities in our nation. There are nearly fourteen times as many people with mental illnesses in jails and prisons in the United States as there are in all state psychiatric hospitals combined. Each year, roughly 2.2 million people experiencing serious mental illnesses are arrested and booked into jails nationwide. Jails are not designed or adequately equipped and staffed to provide the treatment those individuals need.

On any given day, 500,000 people with mental illnesses are incarcerated in jails and prisons across the United States, and 850,000 people with mental illnesses are on probation or parole in the community. (1b)

Nationally, persons with mental illnesses remain incarcerated four to eight times longer than those without mental illnesses for the exact same charge and at a cost of up to seven times higher, making their incarceration a financial burden for taxpayers, as well as, a social/health/justice issue. (2)

The importance of appropriate responses to helping individuals in mental health crises and to diverting individuals who might be arrested into treatment programs cannot be overstated.

The “gold standard” for Crisis Intervention Team training was established by the Memphis City Police Department in 1988 after a (white) police officer fatally shot a (black) man who was mentally ill. Since implementation, Memphis has dramatically reduced fatal police shootings, officer injuries and costly lawsuits. It has also greatly improved police/community relations. The Memphis Model has been widely accepted and implemented throughout the United States.

In the City of Memphis, implementation of CIT training has resulted in an attitudinal shift within the police department as it relates to all of their encounters with the community, a shift from military/aggressive or warrior mentality to a community/service or guardian one.

The Memphis Model requires forty hours of training for law enforcement officers. However, this model is not simply a forty-hour training program for law enforcement officers. Rather, according to its chief architect, retired Major Sam Cochran, the so-called “Father of CIT” the Model emphasizes broad Crisis Intervention Team training. Cochran explained in an email, “Police training is great, but training without supportive state, county, and local support and participation is a cosmetic approach: a Band-Aid approach at best.”

The Memphis Model requires law enforcement, citizens, mental health providers, and the judicial system to work together to achieve two core goals: “(1.) Improving officer and consumer (persons with mental illnesses) safety and (2.) Redirecting individuals with mental illnesses from our judicial system into our health care system.”

How It’s Done – Best Practices

One nationally recognized example of the Memphis Model can be found in Bexar County, Texas, home of San Antonio.

Using a Crisis Intervention Team training approach, Bexar County diverts more than 4,000 individuals in mental health crises into appropriate services at a savings of at least $5 million annually in jail costs and $4 million annually by preventing inappropriate admissions to emergency rooms. Estimated total savings since adopting their variation of the Memphis Model eight years ago exceed fifty million dollars. The use of force in Bexar County inside the jail has gone from fifty incidents per year, to three incidents in six years, according to Bexar County officials.

A key component of the Crisis Intervention Team training approach in Bexar County is the operation of an assessment site where persons in crisis can be taken by police rather than being booked into jail or transported to an emergency room. At this 24-hour center, new arrivals are evaluated by mental health professionals and, when possible, diverted from the criminal justice system into community mental health care.

In Bexar County, individuals who face criminal charges have the option of appearing before a mental health court judge who can direct them into appropriate treatment programs and monitor their compliance rather than a regular district court judge who would sentence them to jail terms where their conditions often worsen and from which they are eventually discharged untreated. These court-involved diversions have proven effective at, in the vast majority of cases, ending repeated arrests.

Here in Fairfax County, the average annual cost of incarcerating an individual in the County jail is estimated to be approximately $50,000. By comparison, the subcommittee learned that the average cost for the (community mental health agency) to serve someone in an intensive case management program is approximately $7,500 per year. (For another estimated $20,000, Housing First can be added. The combination of Housing First and Assertive Community Treatment teams, sometimes called WRAP teams or PAC teams, have been proven to be the most effective at helping persons with serious mental illnesses recover and live within our communities. To find the true cost of operating jails and prisons in your state, click here.)

(Recidivism by arrested individuals with serious mental illnesses averages 85%, much higher than the national average of 65%. According to the Lamp Project in Los Angeles, providing Housing First and intensive services can result in as high as an 80% recovery rate.You do the math: spending twice as much with zero results or cutting costs and helping individuals recover.)”

Read all of the report and recommendations here.

Footnotes:

[1 and1 b] NAMI Public Policy Research Institute document, “Spending Money in all the Wrong Places: Jails & Prisons”, Page 1. http://www2.nami.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Inform_Yourself/About_Public_Policy/Policy_Research_Institute/Policymakers_Toolkit/Spending_Money_in_all_the_Wrong_Places_Jails.pdf

[2] Testimony from Miami Dade County Judge Steve Liefman before the U.S. Senate.

“Several years ago, the Florida Mental Health Institute at the University of South Florida completed an analysis examining arrest, incarceration, acute care, and inpatient service utilization rates among a group of 97 individuals in Miami-Dade County identified to be frequent recidivists to the criminal justice an acute care systems. Nearly every individual was diagnosed with schizophrenia…Over a five year period, these individuals accounted for nearly 2,200 arrests, 27,000 days in jail, and 13,000 days in crisis units, state hospitals, and emergency rooms. The cost to the community was conservatively estimated at $13 million with no demonstrable return on investment in terms of reducing recidivism or promoting recovery. Comprising just five percent of all individuals served by problem-solving courts targeting people with mental illnesses, these individuals accounted for nearly one quarter of all referrals and utilized the vast majority of available resources.”

[3] Email notes from Sam Cochran. http://www.peteearley.com/2010/02/23/a-lecture-from-a-hero-of-mine/

[4] Blueprint for Success: The Bexar County Model, Page 1. http://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/policecommission/subcommittees/materials/jail-diversion-toolkit.pdf