The man at the door said he was doing a background investigation and asked if I could answer some routine questions about the man next door. Most of my neighbors work at federal government jobs that require security clearances so I was not surprised.

The first questions were about criminal activity. Had I seen the police coming to the house? Did I know if my neighbor had a criminal record? Did he seem to spend money lavishly? Had I noticed any suspicious behaviors?

Next came this question: “Do you know if your neighbor has a mental illness? Do you know if he has every been under a psychiatrist’s care or if he is seeing a therapist? Does your neighbor seem stable to you?”

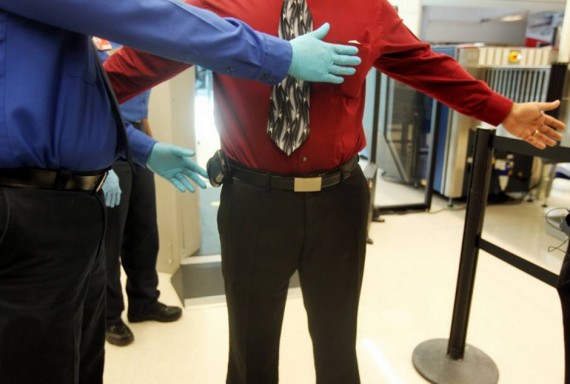

Not long after that exchange, I went online to get pre-approved for the TSA Pre-Select program. I travel a lot and wanted to shortcut the line by not having to remove my shoes or put my toiletries on display when passing through airport security. Sure enough, after answering questions that asked if I had ever been arrested, convicted of a felony, or done time in jail or prison, there were queries about my mental state. Had I ever been a patient in a psychiatric ward, been involuntarily committed, or been diagnosed with a mental illness?

When President Barak Obama held a White House summit on mental illness, he said, “We whisper about mental health issues… there should be no shame in discussing or seeking help for treatable illnesses that affect too many people that we love.”

Yet here I was being asked by a federal official if my neighbor had a mental illness. And here I was being asked if I had a mental illness by the TSA. Those questions were intended to cull a person from the herd. Why?

The background investigator couldn’t tell me how the government used speculation about a person’s mental health. Nor could I find online if the TSA automatically disqualified a person from its TSA Pre-Select program if he/she had been hospitalized. And that troubles me.

Should the government be asking these questions? Where does the right of individual privacy end for a greater public good? Answering these questions can be difficult.

A police officer asked me during a recent meeting if there was a way to identify where persons with mental illnesses live so that dispatchers could alert officers when responding to calls? The officer had noted that between one-third to half of all fatal police shootings involve persons with mental illnesses. If a dispatcher had a way of knowing if someone had an illness, a Crisis Intervention Team trained officer could be sent to the scene. I have received emails from individuals with mental health diagnoses who are angry because they enjoy hunting yet can’t purchase a firearm because they were once involuntarily committed. I’ve gotten letters from students who had a mental break in college and were denied re-entry after they recovered because the schools didn’t want them back. After a Germanwings pilot, who was depressed, crashed a jet liner there were calls for greater review of airline pilots’ medical records.

Given the wide number of disorders now listed in the Psychiatrist’s Bible (the DSM-5) should all mental illnesses be treated equally? Narcissism, schizophrenia, restless leg syndrome. Is someone with anorexia as alarming to the TSA as someone with paranoia and suicidal impulses?

Here’s a thought. Treat mental health the same as physical health. If there is no legitimate reason for the government to pry into your personal health records, they shouldn’t be fishing around asking you generic questions about your mental health. The burden should be on the questioner to demonstrate why that information is germane and necessary — not routinely listed on a questionnaire, especially after queries about criminal conduct.

People who are insightful enough to seek help for a mental illness shouldn’t be punished by the TSA because they would like to keep their shoes on and not remove their toothpaste from their suitcases when traveling. And having a background investigator ask a neighbor if he thinks the man next door might have a mental illness would be comical if it were not so stigmatizing.

If the federal government wants to combat stigma, it should start by looking at how it stigmatizes mental health issues.