“It Shouldn’t Take Killing Your Mom To Get Proper Treatment” — Joe Bruce

9-4-2014

“You have to meet Joe Bruce,” a friend told me. “You need to hear his story.”

I met Joe about a year after his adult son, Will, murdered his mother, Amy, in 2006. That was the same year that I published my book about how my son was arrested for breaking into an unoccupied house after we were turned away from a hospital because he was not considered a danger to himself or others.

The Bruce’s story was clearly much, much worse than our’s.

When I met Joe at a National Alliance on Mental Illness national convention, I was immediately struck by his quiet determination to change our broken mental health care system and by the incredible love that he felt for Amy and his son. Since that meeting, the Bruce family’s story has been told by the Wall Street Journal and other publications, and Joe has testified before Congress.

However, little has been written about Will Bruce and what happened after he was found not guilty because he was legally insane at the time of his mother’s murder. CNN recently broadcast a followup about Will and Joe, that I want to share it with you.

Augusta, Maine (CNN)

Will Bruce strolls across the pale yellow and green linoleum tile of the psychiatric hospital that has been his home for more than seven years.

“So long,” he tells staff members who’ve gathered to see him off. “I hope I don’t come back.”

The last time he was discharged, Will was a different man. He’d refused treatment for 2 1/2 months and gone back into the world the way he’d arrived: confused, incoherent, psychotic.

Two months later, he bludgeoned his mother to death with a hatchet. He believed she was an al Qaeda operative.

Now 32, Will feels the weight of past and future. If he screws up, he messes up everything. For everyone.

Will is part of a special state program in Maine that allows the most violently mentally ill to get treatment after crimes instead of going to prison. Inside Riverview Psychiatric Center are dozens of other forensic patients who’ve killed, assaulted or committed other offenses. They watch Will, and hope to take the same path toward freedom.

On this day in March, Will heads a few blocks around the corner to a 1960s split ranch, a doctor’s office that has been converted into a supervised group home. There he joins seven other mentally ill residents; four, like Will, have killed.

Each remains in the custody of the state but has earned the right to live in the community by following rules, taking medication and abiding by a structured court-ordered treatment plan. The patients walk the streets, eat in restaurants, shop in stores like other residents of Augusta. Though they must report where they are going, they don’t wear ankle bracelets.

But they live with the terrible burden of their actions.

“I don’t think I’ll ever truly forgive myself,” says Will, who was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. “I should have my mom here today. I love and miss her so much. It should never have played out like this, but it did and there’s nothing I can do about it now.”

Will Bruce, 32, is piecing together his life in a group home in Augusta, Maine, after seven years of treatment at a state psychiatric hospital. He killed his mother in 2006. “I don’t think I’ll ever truly forgive myself.”

That’s the reality of regaining your sanity: You face the awful, irreversible truth of what you’ve done. Forgiveness — whether from yourself or others — can remain elusive.

Will knows he wouldn’t have reached this milestone were it not for his father. Joe Bruce gives his son space on the day of the big move, to allow him to take in the moment. But Dad checks in often by phone: “I’m proud of you, Willy.”

There was a time when Joe wanted nothing more to do with his oldest son. When he thought the best treatment for his boy might be a bullet to the head. But he fought unfathomable grief and a stubborn bureaucracy to wrest hope from tragedy. To see his son finally get well.

“All of our happy days have a shadow because of what happened,” says Joe. “I’m so happy for Will, but every time I feel happiness the first thing I think of is: if only they had treated him beforehand.”

On this night, Will settles in his new room after dining on pulled pork sandwiches with the others. The place is barren, the walls drab. But to Will, it symbolizes progress. He marvels at a little thing like having his own bathroom.

On his dresser he has placed a photograph taken on vacation in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. Wedged between Will and his dad, their arms wrapped around each other, is his mom, Amy.

He sits down and logs onto Facebook. He hasn’t posted a status update for three years, and he wonders whether he should do so now. What will those still struggling to forgive him think?

“For all my friends and family who supported me in my new transition, a warm-hearted thank you,” he writes. “This begins a new chapter in my life and will be the beginning of what I hope to be a long line of successes and achievements. It has been a long road fought so far, and I do believe I’ve found meaning in the suffering. For my dad, I thank him tremendously and have found his strength through the difficult times something to be admired.”

The nation learns about the Will Bruces of the world after the unthinkable happens: “Caratunk woman found slain; husband discovers body at home; son surrenders in South Portland” read the headline in the Bangor Daily News on June 22, 2006.

But rarely do we hear about what happens next, after the legal system has run its course. Are the mentally ill simply locked away? And if they get treatment, does it work?

Even more rare is the chance to hear from the mentally ill themselves.

The story of Will Bruce and his father provides a peek into that aftermath. It is a complicated period strewn with anger, immeasurable grief and pain. Faith and family ties are tested. Confounding legal obstacles loom. At best, the mentally ill begin a trial-and-error pursuit of wholeness that unfolds over years, even decades.

It never ends.

Often, family members bear witness to their loved one’s unraveling — and are stymied by a system that is structured for the back end, to hospitalize and treat mentally ill people after they become a danger to themselves or others.

Think of it this way: What if your doctor told you that you had cancer, but treatment would begin only after it reached stage 4.

Families often face an insurmountable obstacle when the mentally ill person turns 18. That is the age when parents can get shut out of their children’s health care decisions. Doctors can no longer legally speak to mom and dad without consent. And treatment cannot be forced on a person who has the right to refuse it.

“I know that treatment works. Unfortunately, I see it after a horrific crime has happened,” says William Stokes, who until recently was Maine’s deputy attorney general, with his office handling every killing in the state.

Or as Joe Bruce told me: “It shouldn’t take killing your mom to get proper treatment.”

There are few bipartisan issues left in Washington, yet Republicans and Democrats alike insist changes to the nation’s mental health system are long overdue. The debate isn’t about whether reform is needed; it’s about how best to implement it — a delicate balance between treatment, civil rights and public safety.

U.S. Rep. Tim Murphy, a Republican from Pennsylvania, has proposed the most sweeping mental health bill in two decades. It’s called the Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, or HR 3717. Among its key provisions: making it easier to commit someone involuntarily and allowing more parental involvement in a young adult’s care.

Murphy is a psychologist who remains adamant that a young person undergoing psychosis or other delusions would be best served by a family member who can help in the recovery. Critics charge that the bill will trample individuals’ rights and cause more harm than good. Murphy remains unbowed. After the mass killings in Santa Barbara, California, in May, he said simply, “What makes these painful episodes so confounding is the reality that so many tragedies involving a person with a mental illness are entirely preventable.”

Amy Bruce’s death was preventable. She tirelessly sought help for her son — even after she no longer had a say in his care.

At 24, Will Bruce became a symbol of the broken mental health care system.

Now, he hopes to stand for something else: the successful rehabilitation of the mentally ill. An example of what could have been achieved had there been treatment before tragedy.

Will is one of 90 mentally ill people in Maine designated as not criminally responsible — known as NCR — because they were determined to be insane at the time of the crimes. Nineteen had faced murder charges before the NCR designation; at least 10 who killed are now living in group homes or group apartments, according to newspaper accounts and records provided by the state Department of Health and Human Services.

All NCR patients are initially sent to Riverview instead of prison. There the focus shifts from punishment to rehabilitation, treatment and public safety — with the end goal of returning the patients back into society.

That goal has met with some resistance in Augusta. In 2012, when Riverview moved its group homes off campus and into neighborhoods, residents responded with outrage. More than 150 signed a petition demanding the homes be closed, citing safety concerns.

But the program’s track record has helped officials resist community pressure. In place more than 50 years, it was revamped after a patient on a four-hour leave killed a teenage girl in 1985. In the past three decades, state officials emphasize, not a single NCR patient released into the community has committed a violent felony. “The history of the experience speaks volumes,” says Mary Mayhew, the state’s health commissioner. “We don’t have an experience of recidivism.”

Will Bruce and his father let me into their lives beginning in early March, the final week of Will’s stay in Riverview. He embraced the risks of stepping into the spotlight, he said, because reaching even just one person undergoing psychotic delusions could save another person’s life.

Will has piercing hazel eyes, a stocky 200-pound frame and short-cropped black hair. A stern expression makes him look older than his 32 years. He collects himself before he speaks, giving well-thought-out answers. When he breaks into laughter, you get a glimpse of the boy his mom tried so hard to fix. His laugh always made her laugh.

Schizophrenics and others with serious mental illness, he says, too often “lack the insight to recognize they’re ill. They don’t believe it. They discard what the doctor says: It’s just psychobabble, mumble jumble.

“From the beginning, I just thought it was all a conspiracy.”

Both father and son know Will’s release is not celebrated by everyone.

Will is not yet allowed to return to his hometown, nor does he want to visit. But some in Caratunk, a no-stoplight town with just two roads and a population of about 50 people, told me they have begun locking their doors. At a bar up the road from the Bruce house, several neighbors shuddered at the thought: How could he be out?

Joe Bruce has an answer for them.

“There’s a big difference between Willy treated and Willy untreated,” he says. “If there’s any message to people with concerns, it’s that he never received treatment before. He’s living proof that treatment works.”

Adds Will, “It really does. It was my mother, you know what I mean? Not a day goes by that I don’t think about her.”

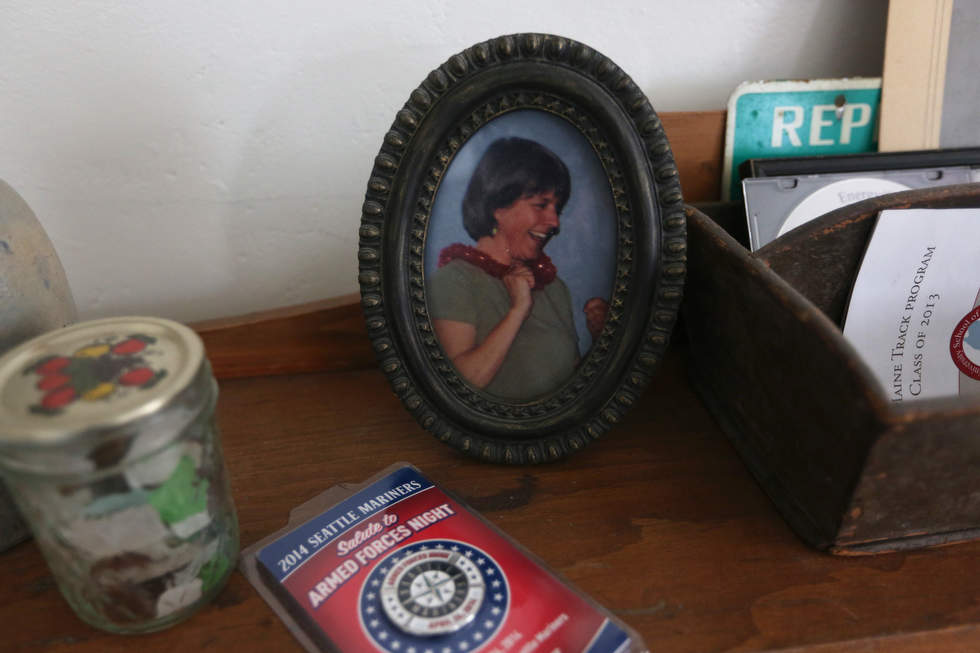

An unframed photograph of Amy sits on a shelf in the kitchen, next to a pitcher filled with wild turkey feathers. She has short hair, a beaming smile and hazel eyes; it’s easy to see where Will gets his looks.

The kitchen in the family’s 1880s farmhouse was the noisy hub of the Bruce household. Amy and Joe found the place after driving through the Upper Kennebec Valley in the early 1980s. They had been living in New Hampshire but liked the idea of moving to the Maine countryside. They turned onto Caratunk’s Main Street; an osprey swooped down, and the young couple took it as a sign: This was home.

The farmhouse sits on five acres shaded by oak, ash, poplar and sugar maple. It became the perfect place to raise three boys. Nothing fancy, but enough room to play and grow. Amy fixed up a workshop on the property and started a slipcover and drapery business.

The house is frozen in time, like a Depression-era Dorothea Lange photograph. Paint peels from the tin ceiling in the living room; wainscoting in the home’s only bathroom buckles. Amy always talked about renovating the place, but finances were tight and the time never right.

After her death, Joe left the house for two weeks, then moved back. He thought it was the best way to heal, to cherish the good memories there. In Caratunk’s heyday, when more people lived in town, there were 27 children within five years of one another. The kids crammed the kitchen, with Amy serving as host.

At her funeral, Joe began the eulogy this way: “I’m the luckiest person in the world.”

They were married 26 years.

Amy Bruce tirelessly sought help for her son Will. Authorities found an undelivered note to him in her wallet after her death: “I will not give up on you. Ever.”

Joe has found peace in the years since Amy’s death. But dark moments still intrude. His other two sons, ages 23 and 19 when their mother died, remain distant from Will. That may never change.

A few days before Will’s release from the hospital, a jumble of emotions collide — the overwhelming joy of his son’s new life and the magnitude of Amy’s absence. At his kitchen table, Joe weeps.

“Amy is with all of us,” he says. “She is part of us. For Will, it’s a struggle. He struggles and we do, too. The better Will does, the better it is for all of us. His mother would’ve wanted it that way.”

Scratched into a nearby bookshelf is a reminder of family life in these four walls. Pen marks record the growth of three boys over the years: Willy, Wallace and Bubba.

Etched between Willy and Wallace in 2000 is one line: “Mom.”

Will was the first child, and never easy.

At 4, he shoved his 3-year-old brother Bob, nicknamed Bubba, down a flight of stairs and broke his arm.

At 5, he pushed Bubba so hard on a seesaw swing that it shattered one of his brother’s legs. Joe used a Newsweek magazine to form a splint until he could get Bubba to the hospital.

At 10, Will twice climbed to the top of the home’s pitched tin roof and threatened to jump off. He had to be talked down.

At 15, he left a note in the home that said: “By the time you find me, I will have injected the antifreeze in my neck.” Joe sprinted to an outbuilding and found Will on the ground, a syringe in his arm.

Will was admitted to the adolescent ward of a psychiatric hospital. Amy and Joe were told their son might suffer from bipolar disorder, but there was no formal diagnosis. Will was prescribed Depakote, an anti-seizure medication sometimes used for psychiatric conditions. Suddenly, he could carry on conversations in ways he couldn’t before. But he complained the pills made his head hurt, and he stopped taking them almost as quickly as he’d begun — a pattern that would persist in the years ahead.

Mom and Dad arranged for Will to meet with a psychiatrist in a nearby town. He rejected the doctor, then a second one before finding a therapist he seemed to like. But he grew more defiant, drinking heavily and smoking weed. He skipped classes and dropped out of high school halfway through his sophomore year.

At 17, Will took his GED test to qualify for the Army. He went through boot camp in the fall of 2000 and advanced infantry training at Fort Polk in Louisiana. Growing up in the country and learning his way around guns helped him earn high marks as a sharpshooter.

Joe and Amy were ecstatic, thinking he had turned a corner.

Will shipped out to Schofield Barracks, an Army installation in Hawaii. It was there, his father says, that Will got into everything from crystal meth to cocaine. One day in 2001, Will showed up at the family home. He was AWOL. He made it back to Hawaii so he wouldn’t face desertion charges. He took a less-than-honorable discharge to avoid jail time for absence without leave.

By then, Will was an adult, in charge of his own health care. Mom and Dad worried about him, but he wouldn’t listen to their pleas.

On Christmas Eve 2003, he was shopping with his father when he announced that government agents were spying on them from cameras inside Target. Another time, when he and a friend stopped at a convenience store, Will went to a house next door and lowered the flag to half-staff.

That’s how it started out — seemingly innocent. No harm done.

Will walked in circles at the end of the driveway, talking to people who didn’t exist. He sent a bottle of homegrown maple syrup to President George W. Bush. He penned a note to Prince William; Will planned to marry a Russian princess, he wrote, and sought the prince’s blessing.

By early 2005, it was clear he was in the onset of a serious mental illness. He was 23 and couldn’t hold down a job. His mom and dad urged him to see a doctor. He refused. Desperate to understand her son’s illness, Amy sought out the state chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, a nonprofit advocacy group. Every week, she drove two hours to Bangor to attend one of its family courses.

On a crisp spring day that year, Joe arranged a machine gun target shoot with two friends. Machine gunning is a hobby in rural Maine, almost on par with rafting and hunting. By day, Joe worked for Maine’s Department of Transportation. At home, he operated as a certified gun dealer, selling everything from shotguns to rifles to machine guns.

He loaded up Amy’s station wagon with an AK-47, M-16 and hundreds of rounds of ammunition, and began to drive off.

Will flagged him down and asked if he could come. Joe never thought of his son as a threat, even if his behavior was becoming more unpredictable. Still, something didn’t sit well about this. But it was too late; Will hopped into the car.

The Bruce family home in tiny Caratunk, Maine, is trapped in time like a Dorothea Lange Depression-era photo. Amy Bruce always joked how it needed renovation.

The four drove about 25 minutes until they reached a thickly wooded area where Joe set up a firing line. The two friends shot the AK-47. Joe gave instructions about the proper way to handle the gun.

The three of them stood talking in a semicircle. Out of the corner of his eye, Joe noticed his son pick up the AK-47 and insert a loaded 30-round magazine. Will approached the group, the gun pointed at the ground. He then cocked the bolt and was ready to shoot.

Willy, what are you doing? Dad said.

Snake eyes possessed his son. Dark circles that weren’t there on the drive out appeared beneath his eyes, like he was demonic.

Will was in the throes of psychosis, and he was about to carry out an execution. He looked at one of the men and shouted: Do you touch little boys?

The man thought Will was joking and gave an awkward laugh. Will turned to the other guy and ordered: Tell me, do you touch little boys?!

He motioned with the weapon like Come on, step over here. He then backed up a few feet. Panicked, Dad moved between Will and the others.

WILLY! WILLY! he shouted. WHAT ARE YOU DOING?

Will snapped out of it for a second. He turned downrange and fired the 30 rounds. Then he handed Joe the gun, almost with a look of defeat, like he knew he’d done something wrong.

Joe’s heart pounded. He had two machine guns in his possession — and a son in psychosis. He put the guns in the rear of the wagon and Will in the front passenger seat. The two friends sat in back, a barrier between Will and the arsenal.

Joe mashed the accelerator. At home, he called authorities. A state trooper arrived.

Will sat mostly silent at the kitchen table, rocking back and forth. He pointed to a light bulb overhead. It’s bugged, he said. It’s bugged.

He was hospitalized in a psychiatric facility under court order.

When he was released a few weeks later, Will walked out the door and dumped his pills in the parking lot.

He would be back in the hospital within several months after attacking his father and splitting open his cheek. He believed his dad had stolen a box of military patches worn by soldiers in Desert Storm.

You’ve disobeyed the orders of senior officers of the CIA, Will shouted.

He was sent to Acadia Hospital in Bangor in January 2006 for psychiatric evaluation for the purpose of a commitment hearing. He was then ordered to Riverview, the state psychiatric hospital, for up to 90 days.

Amy and Joe didn’t know how the treatment was going; their son ordered doctors not to communicate with them. Amy visited him for the first time in early April. She brought treats from McDonald’s and begged him to take medication. He refused.

On April 20, 2006, Will was released. Untreated.

On the wall of her workshop, Amy kept the phone numbers of the Maine State Police and a crisis hotline. But she never stopped reaching out to her son.

When he showed up at his grandmother’s home in Essex, Massachusetts, after his release, Amy drove four hours to pick him up. Before they left, she made up the guest bed where Will had napped.

Under the mattress she found a butcher knife.

Amy and Joe stayed up late the night of June 19, 2006, talking for hours about Will.

They wrestled with the feeling that had gnawed at them for two months: I can’t believe they let him out.

Amy suggested Joe talk with Will’s caseworker the next day. Joe had grown worried that Will might harm his mother. She reassured him the minute she suspected anything she’d sprint from the home. That was the plan.

The next day, Joe phoned Amy repeatedly while he was at work. He also called the caseworker several times. Hours passed with no word from either.

A torrential storm moved in during early afternoon. Rain pelted the ground so hard it bounced two feet into the air. Power was knocked out throughout the region. It was about 4 p.m. when Joe arrived home.

It was dark inside, eerily quiet. Joe noticed what he thought was coffee spilled on the floor. But then the clouds parted and sunlight flooded the windows.

The splotches weren’t coffee.

When Joe discovered Amy’s body in the bathtub, he ran from the home to the front yard, fell to his knees and unleashed a primal scream. Then he moved into a state of hyper vigilance. He went back inside, studied the crime scene, grabbed a shotgun and called 911.

“He got out of Riverview. They committed him and let him out, and said there was nothing they could do for him. He won’t take medication and they won’t give it to him,” Joe told the dispatcher. “The freaking nuts are the ones making these f—ing laws. My wife, she was one of the most beautiful people in the world.”

The dispatcher tried to calm and reassure him: “OK, you are doing great.”

“I’m all right. I’m — my other kids, the rest of the family, the lives that are going to be ruined because of the lunatic goddamn laws,” he said. “We told them that he’s going to kill somebody. They say, ‘Well, he seems OK now so there is nothing that we can do.’ “

Joe Bruce, 62, worked through grief and post-traumatic stress to forgive his son Will. Joe’s dog, Tootsie, has helped in his recovery after his wife’s death.

A handwritten note to her son would later be found in Amy’s wallet.

“I want to fight with you. I want to cry with you. I want to apologize to you. And I want my Willy back. I will not give up on you. Ever,” she wrote. “Please, please, please try to realize that your father and I are doing the best we can. We truly don’t know what else to do. You’ve got to help us, Will. I know you have reason to doubt our ability to protect you from harm, but please give us a chance.”

Will was held for almost four months, in two county jails, until a judge found him not criminally responsible in a trial that lasted about an hour. It was mostly a formality — all sides agreed he was insane. He was sent to Riverview on October 16, 2006.

He remained in psychosis, off and on, for more than a year after the slaying. A psychiatrist noted his state of mind: The patient believed he “was performing only his patriotic duty (his mother was thought to be an enemy agent).”

Not only was Will severely schizophrenic, but he suffered from anosognosia, meaning he was unable to recognize he was ill.

Joe fought his own battle of survival. Coffee spills triggered flashbacks of blood stains. A bee buzzing by his head felt as loud as a jet. He wandered around aimlessly at work. He lost 35 pounds.

One of Amy’s closest friends was a nurse who made Joe promise that he’d see a therapist.PTSD kills, she said, but it’s very treatable.

“I knew what she was saying because I still had two other sons to live for.”

He and Amy had planned a trip to Alaska for more than a year. Joe decided to take the trip with his other sons. They hiked mountains and fished for halibut, trying to lose themselves in the outdoors. But the trip was a mistake, the shock too fresh.

“I thought we’d go in her honor, but the fact she wasn’t there was with us every second.”

By the time Joe returned home, he could hardly function: “It was like being emotionally skinned alive.”

He sought the help of a specialist in post-traumatic stress disorder, but it would take two years to tamp down the anxiety.

On the horizon was a different struggle he never foresaw.