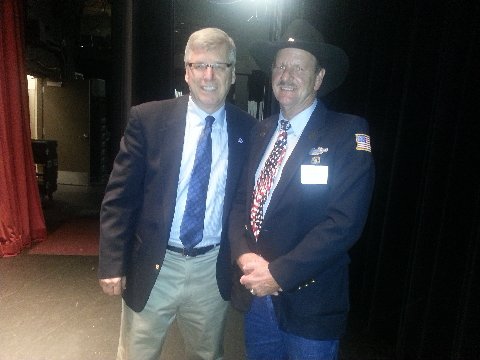

Pete Earley with George Taylor Sr.

Nineteen year-old George Taylor Sr. returned home in April 1970 from fighting in Vietnam a changed man. For more than a year, he had cleared jungle and walked point as part of a unit nicknamed “the herd” that engaged in heavy, repeated combat. He and his comrades were part of the U.S. Army’s 1 battalion 503rd, a company of the 173rd Airborne Brigade.

Taylor had joined the Army two years earlier directly from high school. Serving in the military was a family tradition. When Geoge returned home to Florida, his family didn’t recognize him.

George looked like a much older man who had witnessed too much carnage and lived for too long under the threat of death. He was argumentative and began getting into bar fights, drinking heavily, and had trouble finding and keeping jobs. “It got to the point where I couldn’t deal with people, so I went into the woods,” George recalled later.

For six months, George simply disappeared into the rural Florida landscape, living far away from civilization, much as he had when on patrol in the jungles. When he finally emerged from the woods, he hit the road, roaming the country, often drunk, battling the mental nightmares of his past.

George had Post Traumatic Stress Disorder but that diagnosis was still in its infancy when he returned in 1970 and was not widely understood nor accepted by the Veterans Administration.

George finally got help when his brother took him to a Veterans Administration Center nearly twenty years after Vietnam. He got treatment and emerged wanting to help other veterans who, he knew, had also disappeared into the woods.

With less than $2,000 donated by his family, George founded National Veterans Homeless Support , in 2008, a non-profit group based in Port St. John, Florida, which literally sends volunteers into remote areas of central Florida to find homeless veterans and offer them outdoor gear and food. Once the volunteers make contact, they try to help the veterans find housing and obtain other VA benefits. George claims there are 4,500 homeless veterans currently living in the woods in Central, Florida. This year alone, his group has helped 422 of them find housing. In 2012, the state of Florida gave George’s group a million dollar grant.

George is a difficult advocate to miss when you visit Florida. He can be seen always wearing a black cowboy hat. I met George when I was invited by Gail Cordial, the executive director of Florida Partners in Crisis, last May to speak in Cocoa Beach during a day long symposium. George warned that recent surveys showed that 22 veterans a day commit suicide – that is nearly one per hour!

George used his own experiences to identify a problem. No one was searching the woods for veterans. He came up with a solution. He is a wonderful example of the power of one person to bring about social change. The question is: how many homeless veterans are there in other states who have disappeared into the woods? What can we do to help find them and offer them housing and help?

Today is Veterans Day. On any given night, between 130,000 to 200,000 veterans are homeless. Many have mental illnesses. Twenty-two suicides a day is unacceptable. Our veterans deserve better. If we want to honor them, we need to remember and help them – not only today, but every day.