I was in Dallas giving a speech when news broke that Aaron Alexis had heard voices and appeared to have a mental illness. I was asked about the Navy Yard shooter during interviews with the local NPR affiliate at KERA radio and with the Dallas Morning News. While I always point out that persons with mental illnesses are more likely to be victims of violence rather than committing it, I took a different approach in both interviews.

I was in Dallas giving a speech when news broke that Aaron Alexis had heard voices and appeared to have a mental illness. I was asked about the Navy Yard shooter during interviews with the local NPR affiliate at KERA radio and with the Dallas Morning News. While I always point out that persons with mental illnesses are more likely to be victims of violence rather than committing it, I took a different approach in both interviews.

I said we need to acknowledge that some individuals are dangerous but what keeps most of them from acting out is that they get meaningful treatment. I hoped to tie the need for treatment to these horrific and reoccurring tragedies.

Fortunately, NPR’s Krys Boyd and the Dallas News’ Christina Rosales didn’t sensationalize my remarks as they easily could have.

I am grateful to both and to Dallas MetroCare for inviting me to speak at its Meal for the Minds fundraiser. Dallas is an example of how things should be done. There is great cooperation between mental health services, the jail, the police, and the judiciary. Unlike in most cities, an individual in Dallas in the midst of a psychotic break can see a Dallas MetroCare therapist within 24 to 48 hours. Dallas MetroCare also is involved in Housing First and has recently launched SNOP — Special Needs Offenders Program— to help persons with mental illnesses who are in the criminal justice system while they are incarcerated and when they are released into the community. I’ll write more about SNOP later because it is such an impressive program, but here is what I said in my interviews.

By CHRISTINA ROSALES

Staff Writer Dallas Morning News

crosales@dallasnews.com

Author tells Dallas crowd mental illness like Navy Yard gunman’s can be treated

Scan the halls of a community mental health treatment center, and chances are you’ll see someone like the Navy Yard shooting suspect, author Pete Earley says.

“But they don’t go out and shoot if they get the help they need,” said the mental health advocate, who spoke Wednesday in Dallas. “That person could have been stopped from doing that if someone had gotten to him and helped him.”

Earley appeared at the annual fundraising luncheon for Metrocare Services, a 45-year-old nonprofit that serves the mentally ill and developmentally disabled and offers outpatient clinics, rehabilitative programs and homeless services.

The former Washington Post reporter has written dozens of articles about the criminal justice system and several books, including Crazy: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness. In the 2006 book, the Pulitzer finalist wrote about the American criminal justice system’s relationship with the mentally ill.

In Texas, Earley said, someone with a serious mental illness is eight times more likely to be incarcerated than find help in a psychiatric hospital. And the largest mental health facility in the state? The Harris County Jail.

“In our country, someone has to be a danger to themselves or others before there can be any intervention and before they can get treatment,” the author said.

And by that time, in some cases, it can be too late.

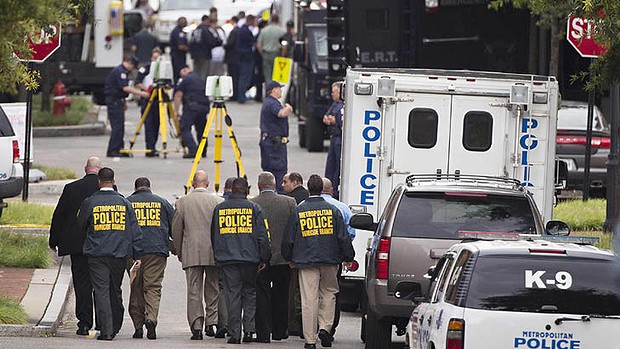

That was the case Monday, when 34-year-old Aaron Alexis opened fire at the Washington Navy Yard, killing 12 people and injuring several others. Officials said the former Fort Worth resident had a history of hallucinations and hearing voices.

Dr. John Burruss, chief executive of Metrocare, said the common thread connecting too many of these acts of violence is mental illness.

“There are the same stories happening,” he said. “The Navy Yard, at Virginia Tech, in Tucson. But how do we know who those people are?”

Ron Stretcher, Dallas County director of criminal justice, said that many people in jail — more than 400 every day — are awaiting behavioral health treatment. And many, once released, will be incarcerated again within a few years, he said.

“You have to do something bad to get into treatment,” Stretcher said. “We have to make it so our system in this community is welcoming and recovery-oriented.”

But Burruss believes services such as the kind Metrocare offers should and can be more accessible, whether it is through a nonprofit or another health care provider.

Of the 50,000 people treated annually by Metrocare, the majority do well, Burruss said.

“You can’t know what didn’t happen,” Burruss said about the many who don’t commit acts of violence. “We don’t hear about them not doing something. And every

day we’re helping people not do something. There’s just more to be done.”

Link to NRP interview: http://keranews.org/post/think-how-does-criminal-justice-system-address-mental-illness

Link to