FROM MY FILES FRIDAY: I first published this blog in December 2010, yet the question that it poses is just as haunting today.

WHO IS TO BLAME FOR THIS DEATH?

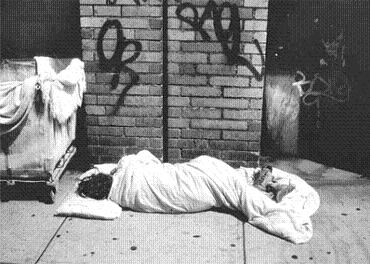

The residents of Morrisville, Pa., got an intimate look this holiday season at our troubled mental health care system. Paulette Wilkie, a homeless woman with a long history of schizophrenia, was found dead from exposure. The 56 year-old woman’s body was discovered last week behind Ben’s Deli, a sandwich shop that she frequented.

Temperatures the night before had dropped into the mid 20s. But that was not cold enough to trigger the county’s emergency homeless plan. Temperatures must sink to 20 degrees or below for two consecutive days before teams can be dispatched to try to persuade homeless persons to come indoors.

Reporter Ben Finley, writing in the Bucks County Courier Times, noted that people who knew Wilkie said she likely would not have gone into a shelter anyway. The owner of Ben’s Deli said Wilkie refused help from people concerned about her safety and health.

Reporter Ben Finley, writing in the Bucks County Courier Times, noted that people who knew Wilkie said she likely would not have gone into a shelter anyway. The owner of Ben’s Deli said Wilkie refused help from people concerned about her safety and health.

Wilkie’s father said his daughter had been in-and-out of a local community mental health center for more than 20 years. She’d lived in a group home until last year. Another resident said Wilkie was asked to leave after she stopped taking her medication. Wilkie’s father said his daughter did not like to take her medication. He said mental health officials told him that she couldn’t move back into the group home until she “got back on the medication and was clean.” Her father added that his daughter had been hospitalized about a month ago and that he probably should have moved her into his house when she was discharged, but that he was concerned about doing that since she was not taking her anti psychotic pills.

The owners of Anthony’s Pizza and Ben’s Deli said Wilkie was a regular fixture on their street. Everyone knew her and knew that she had a mental disorder. She always wore the same parka, its hood lined with fur, even in the summertime. Shortly before her death, the two business owners said they noticed a sharp decline in her mental health. She was losing weight and had stopped bathing.

On the weekend that she died, Wilkie had gone into Anthony’s Pizza, but the store’s owner had asked her to leave because she smelled very bad and customers were exiting the store. “My wife was here and she said (Wilkie) is going to freeze out there,” the owner told the newspaper. Wilkie was last seen sitting on a picnic table behind the deli with her socks and shoes off, smoking a cigarette.

While I do not have inside information on Wilkie’s death, she is not the first person with mental illness to freeze to death on our streets.

Could her death have been prevented? Absolutely.

The first question we need to ask is why was this woman homeless?

I’ve heard people say that homeless persons prefer living under the stars rather than being inside. I’ve found this rather romantic notion to be hogwash. Even the sickest homeless person I’ve met doing my research has wanted a warm and safe place to sleep at night. Unfortunately, overnight shelters often are dangerous. Other housing programs are rule oriented and restrictive.

The solution here is Housing First.

Housing First does not require a homeless person to take medication or to stop using drugs/alcohol before he/she moves into an apartment. Instead, that individual is given a safe place to live because no one can get better mentally or physically if he/she is sleeping on the street.

Most Housing First programs require tenants to pay a percentage of their income for rent. You earn zero, you pay zero. Tenants also are required to meet with a treatment team once a month. In many cases, the team is able to establish a relationship with the tenant. Team members work with tenants to get them the services that they need to control the symptoms of their mental disorders and/or beat their addictions.

In addition to Housing First, communities have had great success with Assertive Community Treatment teams, composed of specialists who visit persons who are homeless. Oftentimes, these teams have doctors, therapists, peer-to-peer specialists, and job and addiction counselors on them. Their job is to try to get homeless, psychotic persons off the streets and into shelter and services.

Those are just two programs that can help persons who are homeless and have a mental disorder.

What if there are no Housing First facilities or ACT teams?

There are other alternatives to allowing someone with a brain disorder to freeze to death on our streets. The most obvious is involuntary commitment to a hospital. But that alternative has been undercut by civil rights activists. As a society, we have decided that we are not going to help someone such as Wilkie until she reaches a point where she presents a clear and “imminent danger’ either to herself or others. I believe the “dangerous” criteria is a poor one because no one can predict dangerous behavior and waiting until someone becomes dangerous often results in an ill person being arrested or committing an act that harms them or society.

In recent years, states have added other common sense criteria, such as whether a person is “gravely disabled” or “unable to care for themselves.” But many judges remain reluctant to force someone into a hospital against their will unless there is obvious danger. We need a better criteria.

Wilkie’s death shows the folly here. She had a long history of schizophrenia. The people who encountered her noticed that her mental condition was deteriorating. The temperature was dropping below freezing and she was last seen sitting on a park bench with her socks and shoes off. Yet, it’s unlikely that she would have met the dangerous to self or others criteria. This is why we need to adopt a more sensible standard.

Of course, involuntarily commitment is only useful if a person actually gets meaningful medical care and social services after they are committed. Ordering someone to a hospital for a shot of Haldol and then having a doctor shove them out the door may be a temporary solution. But it rarely helps anyone recover.

Another law that might have saved Wilkie’s life is Assisted Outpatient Treatment. In its simplest form, AOT laws permit a judge to order an ill person to take medication if they meet strict criteria. Usually, the person has to have a history of violence or of frequent hospitalizations. Medication also has to have been shown to be effective in helping the person control the symptoms of their disorders. If a person doesn’t comply with AOT, the judge can involuntarily commit them to a hospital.

Wilkie’s father was quoted saying that “someone dropped the ball.” That’s a bit too easy of an explanation for me.

I suspect community mental health officials felt their hands were tied. They’d done everything they felt they could do based on their meager resources and restrictive laws. Her father admitted that he couldn’t care for her when she was off her medication. The police said that she was not breaking any city codes. And based on her own actions, Wilkie didn’t want anyone to help her.

So who, if anyone, is to blame for her death? Mental health professionals? Her family? The police? Civil rights advocates? Or Wilkie herself?

How about all of us – for not demanding that persons such as Wilkie get the meaningful community mental health and housing services that they need to recover and for not modifying our laws so that if those services fail, we can intervene?

When did we decide as a society that it’s acceptable to walk by a woman with a serious mental disorder who is sitting on a park bench not wearing any shoes or socks in freezing temperatures and say, “Oh well, she’s not dangerous, so it’s none of my concern?”

I’M ON VACATION AND NOT ACCEPTING COMMENTS TO THIS POST.