Parents of Children with Mental Illness

See Things Through a Different Lens

A guest blog by Joseph Meyer

A few weeks ago, President Obama spoke about the lens of personal experiences through which African Americans see life in the United States and how it impacts their perceptions. Several months earlier, in response to the Newtown tragedy, the President called for a national conversation about mental illness. Today, I am writing about the lens that colors my perceptions as the father of a child with severe mental illness in the United States.

When mental illness strikes young children, parents are often confused about what is happening—we question our own parenting skills, wonder if there is something we did wrong, and spend a lot of time and money searching for answers. We also hear a great deal of criticism and unsolicited advice from strangers, friends, and family: “You’re too permissive; I’d never let my child get away with that behavior” or “My pastor says kids with those types of issues have parents who are devil worshippers.” I believe such thoughts are in the minds of some strangers when they see my son come unglued in public, because I had critical thoughts about misbehaving children and their parents before becoming the father of a child with bipolar disorder.

On the outside, children with mental illness look no different than other youth and their symptoms may appear to be disciplinary issues. Educators even refer to their symptoms as behavioral or emotional disorders, implying that bad parenting is an underlying cause. Despite a poor scientific understanding of what causes mental illnesses, they are often unjustifiably blamed on parents.

A recent blog by a clinical psychologist cited neglect and spoiling in childhood as strong explanatory factors in the development of borderline personality disorder. But, genetic studies show the risk for many mental illnesses is highly heritable—for example, the National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder estimates that inborn factors explain 52-68% of the risk for Borderline Personality Disorder with the remainder tied to environmental factors that may include bad parenting, exposure to chemicals in food, infections by viruses, or any number of other issues unrelated to parenting.

The reactions of onlookers to mental health crises involving children who appear normal on the outside are unpredictable and vary from wonderful in rare instances to unhelpful in most cases. When a stranger’s righteous indignation about our child’s misbehavior comes into play, there seems to be a tendency to draw moralistic or religious conclusions—it was once my own inclination, before parenthood, to assume that extreme misbehavior in children was rooted in the moral or ethical shortcomings of parents. Perhaps such thinking is why mental illnesses are more typically handled in the U.S. criminal justice system than in hospitals. Strangers have twice offered to call the police for my wife when our son was unstable in public, but they have never offered to call for medical help. And, if our country’s reliance on the police for medical crises of a neurological nature is not disappointing enough, a study summarized in the December 2012 issue of Salon magazine found that 50% of people who are fatally shot by the police in the U.S. suffer from a mental illness. Crisis Intervention Training has improved the odds of good outcomes, but tragedies still happen when parents dial 911 for help.

Even after patients with unstable mental illness are peacefully taken into custody, our criminal justice system looks unfair to me. Perpetrators of petty crimes caused by the symptoms of mental illness go to jail where medical treatment is poor and symptoms worsen. As for serious crime, an adult with schizophrenia can be subjected to capital punishment in the United States, while a healthy 17-year old is exempted by a 2005 Supreme Court ruling that a minor is less culpable due to a brain that is not completely developed.

This contrast does not make sense to me, because a typical 17-year old has far more insight than a psychotic adult. And, the insanity defense is no solution—it is rarely successful now that the burden of proof has been shifted to defendants, a change in federal and many state laws implemented after John Hinckley was found not guilty by reason of insanity for his assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan. Many were appalled at the lack of punishment in the Hinckley case, but I no longer believe in retributive justice for those with serious mental illness: I have heard Adam Lanza, James Holmes and Jared Loughner called evil monsters, but see them as victims of their illnesses. Perhaps what they did is unthinkable to us not because of moral superiority, but because we have healthy brains. They should be removed from society for public safety reasons, but punishment for behavior related to mental illness is pointless and cruel.

Unthinkable actions can result from psychotic brains. Early psychosis is rare, but my son became psychotic at a young age. I can vividly remember the first episode. One day, after I picked him up from school in the first grade, he said:

“Dad, something strange happened at school today. I was sitting in the classroom when floating skulls appeared around the ceiling near the walls. The walls then disappeared and there was a mountain village being attacked by a dragon swinging his tail to knock down the homes of people who lived there. They were calling for me to help, but I could not get to them.”

When I asked him if his classmates were there with him, he said they had faded to gray when the walls disappeared, but the mountain scene was in color. At night, he began tapping and scratching on his bedroom wall, communicating with friends who lived inside with his ear pressed against the plaster. Walking through a forest with me some days later, he stopped suddenly and pointed to an open area, asking who was standing there only to add “never mind, he’s gone”. After school, he began to speak of portals he could open at the base of an oak tree to go places where others could not follow—he talked of accessing the electrical wiring and plumbing of his school building to play pranks on the teachers and principal. At a public park, he fashioned a tomahawk and tried attacking a group of disc golfers who were trespassing on his land.

For a time before he was hospitalized, he even believed himself to be half cat. My wife and I let these episodes continue for six months, hoping psychotherapy and encouragement to avoid visiting these bizarre places would ground him in reality. But, our son told us that he found psychosis fun; he actively pursued it until years later he began to have scarier hallucinations that involved blood and gore. The therapist eventually could no longer communicate with our son who was growing more and more disengaged from reality—everything coming out of his mouth was rhymes and loose associations (i.e., word salad).

It is understandably difficult for a parent who hasn’t experienced such things to believe that a 7-year old child can be psychotic and suicidal. I probably would not believe it if I hadn’t witnessed, fought, and lived with it. Our son was psychotic and suicidal on many occasions—asking us to kill him and threatening to jump into traffic. And, in case you didn’t know, the lifetime risk of death by suicide for people like my son is higher than the risk of death for those with childhood leukemia or Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

While struggling to decide whether to use medications to treat our son’s psychosis and mood swings from mania to depression, we read many criticisms from legislators and journalists who knew nothing of our son’s struggles but had plenty of opinions to share in magazines and newspapers—they were mostly about the irresponsible parents who would put their children on dangerous psychotropic medications, since they were too lazy to do the hard work of parenting. We sought second and third opinions from neurologists, psychiatrists, and psychologists who repeatedly told us that our son was severely ill and needed treatment. Even then, my wife and I did not immediately begin to medicate our child. First, we educated ourselves about the relative risks (e.g., diabetes and movement disorders) of the different medications by reading journal articles and making choices that seemed to be safest. But, ultimately, we did choose medication and psychotherapy to improve the chances that our child could live a relatively normal life and merely stay alive. Few people would criticize parents for relying on chemotherapy to treat childhood leukemia, but many are highly critical of parents who medicate children to treat more deadly mental disorders.

Writing about our parenting decisions is distasteful to me, because I should not have to justify the impossible decisions my wife and I have faced. But, this is a difficult lens for others to see through. I know that I had many of the same thoughts as my critics before living this parenting experience. Readers may still think I’m a bad parent, may be disgusted by my son’s behavior, or appalled that I would put my child on psychotropic medications. For my part, I am disappointed that safer treatments do not exist and worry about the long-term effects of medications on my son. But, I know suicide is a lifelong risk for my child and worry about it also.

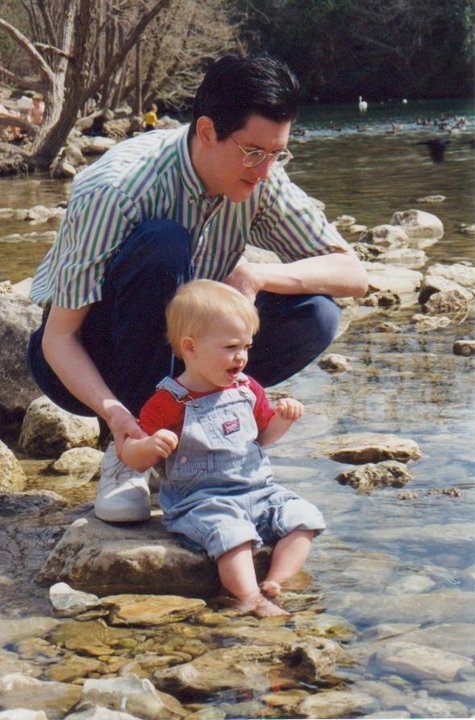

We love our son.

My wife gave up her career to stay home with him and is still unable to work outside the home 15 years later. We spend thousands of dollars annually on our son’s treatments and worry about what may happen when we are no longer able to care for him. Will he become homeless or a resident of the prison system? We don’t know and live day to day without a lot of direction, like other parents of children with severe mental illness. Ten years ago, I sat in my car and sobbed to these words on National Public Radio from a story about a troubled boy who ran into the snow naked and upset, before being retrieved by his parents who wrapped him up with themselves in a woolen coat and walked back home:

“When we get to the house, before we separate and rush for the door, for a single moment I almost speak. I almost say, ‘We’re home.’ But I cannot tell a lie. I don’t know that we’re home, because it’s as if we don’t belong anyplace on this earth, in any country, or any house, or anywhere, really, but in this ragged circle of wool”—from Robyn Joy Leff’s short story, Burn Your Maps.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Joseph Meyer, Director of Institutional Research at Texas State University, was diagnosed with depression a few years ago and is the adoptive father of a teenager who was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder with psychotic features when he was seven years old. Along with his wife, Beth, the Meyers first wrote for my blog about their experiences at the 2013 National Alliance on Mental Illness convention held in San Antonio this summer. Joe is organizing a Common Experience program called ‘Minds Matter: Exploring Mental Health and Illness’ at Texas State University that will offer an academic year of presentations, discussions, and workshops on the topic of mental illness. A webpage with more information about the Common Experience topic can be found at www.txstate.edu/commonexperience and a Facebook page is available at www.facebook.com/MentalHealthandIllness.

COMMENTS WILL NOT BE POSTED ON THIS GUEST BLOG

YOU CAN REACH JOE AT joe.meyer@txstate.edu