Photo courtesy of Slate.

(1-20-20) “I know he’s innocent,” Bryan Stevenson, the author of Just Mercy and real life star behind the movie by the same name, assured me when we first talked in 1991.

This was before Stevenson was famous – when he was in the midst of trying to prove that Walter “Johnny D.” McMillian, an African American death row inmate in Alabama was innocent of murdering a white teenager in Monroeville, the town that Harper Lee used as her inspiration for the classic, To Kill A Mockingbird.

My good friend, Walt Harrington, had urged me to call Stevenson after I mentioned my interest in writing a book about the death penalty. Harrington was among the first journalists to “discover” Stevenson, years before he began receiving international attention (appearing on Oprah and Ellen) for his tireless efforts to save children and adults sentenced to death. [Read Harrington’s story about Stevenson here.]

I warned Stevenson that if I investigated Johnny D.’s case and felt he was guilty, I’d write that. Without hesitation, Stevenson invited me to Alabama.

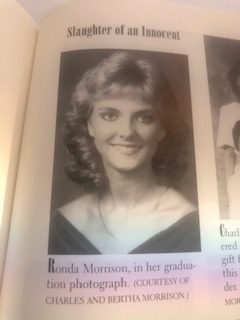

During the next three years, I interviewed eye-witnesses, followed Stevenson’s legal fight and did my best to discover the truth about who had murdered Ronda Morrison, a white teen found dead in a main street laundry on a busy Saturday morning.

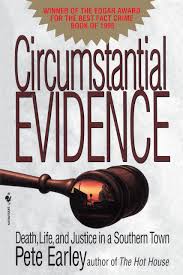

My account, Circumstantial Evidence: Death, Life, and Justice in a Southern Town, published in 1995, won a Robert F. Kennedy Book Award and an Edgar for Best Fact Crime Book.

So let me share my thoughts about Just Mercy, the movie, and additional information you might find interesting after watching it.

The movie follows events closely except for a few minor Hollywood embellishments. One oversight is no mention of Mike O’Connor, a white attorney who worked closely with Stevenson investigating Ronda’s death. He played a vital role in finding evidence but the scriptwriters ignored him in favor of featuring the working relationship between Eva Ansley, the Equal Justice Initiative office manager, and Stevenson.

While Michael B. Jordan and Jamie Foxx did excellent jobs playing Stevenson and Johnny D. respectively, Tim Blake Nelson’s portrayal of Ralph Myers was so dead on that when I closed my eyes, I thought I was sitting across from him. As detained in my book, Myers had been badly burned on his face as a child which caused him to speak out of one side of his mouth, which Nelson captured perfectly. I remember standing in front of a vending machine in prison with Myers and realizing that he could not read when he pointed at items to tell me what he wanted.

The movie mentions that Monroeville investigators offered to help Myers get a lighter sentence in a prior murder in return for his false testimony. That murder was the killing of Vickie Lynn Pittman in nearby Brewton, Alabama. Myers and Karen Kelly, a white woman from Monroeville who was having an affair with Johnny D., were accused of committing that killing.

Sadly, in real life, Vickie Pittman’s murder was largely ignored because investigators were more concerned about solving Ronda’s death. As my book documents, this is because she was considered “white trash” while Ronda’s family was well-liked and admired in Monroeville. A sign that the justice system treated poor whites much differently from whites who were prominent.

Just Mercy ends by noting that a white man was later identified as a suspect in Ronda Morrison’s death. That’s true. Alabama Bureau of Investigation Agents Thomas Taylor and Thomas Greg Cole reopened the murder probe after 60 Minutes raised questions about it.

Taylor and Cole quickly determined that Ronda’s murder was a sex crime, not a robbery. (She’d been found with her blouse open and bra pushed off her breasts.) Monroeville investigators had claimed Ronda was shot during a robbery and drug deal and her blouse had been torn open during a struggle. This theory fit perfectly with their false case against Johnny D. who they claimed was a local marijuana dealer laundering money through the cleaners.

Ronda’s blouse had been unbuttoned, not ripped open, and her pants unzipped.

Once they established her death was a sex crime, the two ABI agents quickly identified a suspect who I identified in my book with a pseudonym, Howard Demar, because he was never charged.

Once they established her death was a sex crime, the two ABI agents quickly identified a suspect who I identified in my book with a pseudonym, Howard Demar, because he was never charged.

Demar had shown an unusual obsession with Ronda’s murder having gleefully offered suggestions about possible killers to the local police and also Stevenson. He’d also contacted Ronda’s parents offering his advice – an especially cruel act if he were the killer. As I note in my book:

“It seemed that every time someone new got interested in the case, Denmar showed up at his doorstep…”

At first, Demar was eager to meet with the two ABI agents but began backing away when he realized that he’d become their suspect. Having heard that I was writing a book, he contacted me. I invited him to my hotel room for an interview – he didn’t want me coming to his trailer – and when I asked him to tell me what he thought had happened the morning Ronda was murdered, he eagerly began explaining that the killer probably had been making phone calls to the cleaners when Ronda was at work. The caller didn’t identify himself but flirted with her.

“Okay,” Denmar said, having set the stage, ‘Here is my theory.’ On the morning of the murder, the caller had been more direct when he telephone Ronda. “He comes on to Ronda,’ Denmar explained. “Maybe this call is obscene.” She gets upset and is trying to figure out who has been telephoning her…”Let’s just say maybe, the caller walked into that place of business on that Saturday morning and Ronda…suddenly put a voice to he face. She suddenly knows who has been calling her…”

“At that moment Ronda would have become angry…She would have verbally confronted her caller. Maybe she had even threatened to call the police or tell her father. An argument had started. Maybe she had reached for the telephone.

“‘I’m saying it wasn’t premeditated…’ The caller had not intended to pull out his pistol, but suddenly he did exactly that. Lots of men in southern Alabama carry pocket pistols. The killer had then ordered Ronda into the back of the store. Maybe the gunman had gotten angry and lost control.. Maybe he thought Ronda would enjoy having sex. Maybe ‘it just happened,’ Demar said. “Someone panicked.’

The ABI asked me later what Denmar had said and since he’d agreed to let me quote him in my book, I shared our conversation with them. The two agents brought him in for questioning and he repeated much the same story. They later discovered Denmar had harassed a former girlfriend who had rejected him. Other women stepped forward.

The agents recommended charging Denmar with Ronda’s murder when they completed their investigation but local officials refused and Denmar fled town. He was from a prominent family.

Just Mercy does an excellent job showing how race, ignorance and prejudice led to the wrongful conviction of Johnny D. Incredibly, there are some in Monroeville who continue to believe that this innocent man was the killer. The movie showcases Stevenson’s admirable lifelong efforts to save death row inmates.

What may be easily forgotten by movie goers is that our criminal justice system not only failed in convicting an innocent man but failed to find the guilty one.

I spent time with Charles and Bertha Morrison and saw how their only daughter’s death and local bungling of the investigation haunted them as only a parent who has lost a child to murder can imagine.

Ronda’s killer remains free. The false accusations against Johnny D. were unjust. And those who loved Ronda are still waiting for justice to be served in her death.

(You can read more about fact vs fiction in Just Mercy, an article published on Slate, here.)