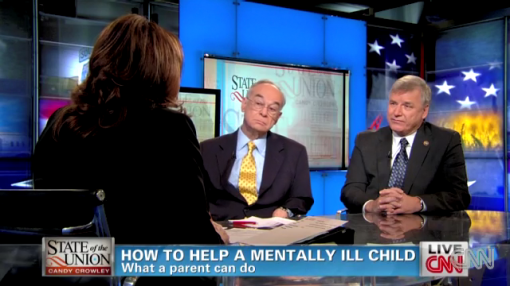

Fred and I often appeared together on national broadcasts

(11-1-19) FROM MY FILES FRIDAY: My final speech of this year took me to Akron, Ohio, where I spoke at an Akron Roundtable luncheon on Thursday (Halloween.) The Peg’s Foundation and Community Support Services of Akron sponsored my appearance. My thanks to Michael Gaffney, Victoria Romanda, Thom Craig, Jocelyn Dougherty, Bill McGraw and Rick Kellar for making my appearance possible. I was especially happy to see Penny Frese, a Pegs’s Foundation board member. Her husband, Fred, was a tireless mental health champion and good friend, and it was gratifying to see her still being a strong voice for our cause. He is missed.

Mental Health Advocate Fred Frese Passes: Major Loss For Those Fighting For Reforms

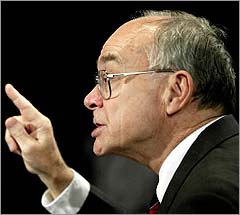

(7-18-18) Mental health advocate Frederick J. Frese III has died.

He was a mentor, a tireless activist, and a good personal friend. He also had schizophrenia.

Fred and I appeared side-by-side on national television programs several times, but we were together the most, along with his loving wife, Penny, when giving speeches at mental health events. He was an incredibly engaging speaker. I remember having to follow him in California after he had spoken extemporaneously for two hours! No one in the audience had wanted him to stop. He received a standing ovation.

He talked openly and bravely about his illness early on when others were reluctant to even say the word schizophrenia, quietly demonstrating by his actions that individuals with arguably the most debilitating psychiatric disorder can live extraordinary lives.

Fred could be funny.

A U.S. Marine when he became sick, he once convinced a prominent general to write him an impressive job reference letter. What no one knew was the general had penned it when the two of them were on the same mental ward being treated for delusions.

He often joked that he was one of the few Americans who had proof that he was not insane. That was because he had been given a certificate saying exactly that after he was discharged from a hospital.

Fred criss-crossed the country speaking. More than two thousand times. Penny was always with him. Their’s is a true love story.

Fred died July 16 at his home in Hudson, Ohio. He was unique in many ways. Fred was an unflinching advocate for “consumers.” At the same time, he spoke openly about how essential medication was to his stability. He was leader in the National Alliance on Mental Illness, later helped found the Treatment Advocacy Center and became an advocate for Assisted Outpatient Treatment, which angered some of his peers. I remember him telling me how grateful he was that he was not left homeless and abandoned on the streets.

I will miss him terribly and will remember, most of all, his kindness. He had a huge heart. When my son, Kevin, was grappling with his illness, Fred came down into the audience after giving a speech and sat with Kevin. That fact that Fred was a renowned psychologist, had worked as a director of a state hospital for fifteen years, was happily married and was a father, gave Kevin hope.

All of us who care about persons with mental illnesses have lost a good friend.

(Have a good story about Fred? Please share it on my Facebook page.)

READ TAC tribute to Fred here. NAMI Tribute to Fred is here.

Schizophrenia could take Fred Frese far away, but it also gives him a niche in life

At red lights, he’d stop walking, no matter where he was on the block.

When he got to church, he knelt by the priest, and when the priest asked him to leave after Mass, Frese felt a change come over him. He barked like a dog, then grunted like an ape. He fell to the floor and writhed like a snake. A few life forms later, he became a tritium atom – the kind used to build a hydrogen bomb – and knew he was going to be split, triggering a nuclear blast to start World War III.

God, he believed, had chosen him for the mission.

“I was the instrument that would wipe out the universe,” Frese said dryly, slouched in a lawn chair on the patio of his Hudson home.

He remembered blacking out at the altar. When he came to, he thought he’d triggered Armageddon and was in heaven.

In fact, he was strapped to a table in a psychiatric hospital. His elaborate delusions were born of schizophrenia, a brain disease characterized by the loss of contact with reality. The cause of schizophrenia is unknown, but thought to be an interaction of genetics with life experiences. The disease is treated with medication.

It wasn’t Frese’s first psychotic break, nor was it his last. He cycled in and out of mental hospitals for 10 years, escorted by men in white coats. And the respected professional would like everyone to know.

“I refuse to hide in the shadows and be ashamed,” he said, a bit of his Texas childhood in his voice.

“There’s tremendous discrimination against [the mentally ill]. You can’t put us in ‘the back of the bus’ in mental hospitals.”

The mental health industry is built on confidentiality, he said, and secrecy only reinforces the stigma.

“It’s so obvious to me that the people who say they are protecting us are perpetuating the shame. . . . The professionals shouldn’t assume the patient is ashamed of the illness.”

He speaks from the perspective of both patient and mental health professional.

Frese, 66, was unemployed for a year after his psychotic break in Milwaukee, his master’s in international management useless with his medical history. When a friend suggested he could help him get a job in the state mental health system, he took the state test to be a certified psychologist. It was 1968, when a psychology degree was not required to take the test. He began working with the mentally ill in prison.

The work agreed with him, and he decided he’d need a doctorate in psychology to gain credibility in the field. He earned the degree in 1978, and was director of psychology at Western Reserve State Hospital, a now-defunct psychiatric hospital, for 15 years before he retired.

“I was able to keep a job,” he said, ripping apart an onion bagel. “Isn’t that amazing?” He buttered a bit, and chewed it thoughtfully. “If they hadn’t come up with these wonderful pills, I’d still be hospitalized.”

Frese is certain his illness gives him a better understanding of people with schizophrenia, and that his openness makes him a role model for others with the disease. He travels about half the year, giving speeches nationwide – more than 2,000 so far. He’s testified at congressional hearings and appeared on ABC’s “Nightline” four times “when they needed a schizophrenic with a Ph.D.,” he said, quite amused.

Changing attitudes, about illness

Frese’s speeches benefit mental health professionals, too, said Nancy Little, training director of Thresholds Institute, Chicago’s largest mental health agency. “We were amazed that this person had an advanced degree and a high position in mental health. He totally changed our view of what people with schizophrenia could do.”

And he has a one-of-a-kind ability to convey the experience of schizophrenia with humor, said Mark Munetz, chief of the Summit County Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services board, where Freseworks half-time coordinating recovery groups.

In fact, Frese delights in calling himself a stand-up schizophrenic.

“That’s my gig!” he said. “When I started speaking, people couldn’t believe a schizophrenic could talk.”

Actually, people thought schizophrenics could talk, but only to themselves on street corners. Frese was delighted when the 2001 film, “A Beautiful Mind,” challenged that tired stereotype with the story of John F. Nash Jr. Nash, a mathematician with schizophrenia, won the Nobel Foundation’s Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in 1994.

“The movie resonated,” Frese said. “We weren’t portrayed as monsters like Hannibal Lecter or Norman Bates. I thought, ‘Heh-heh, we schizophrenics aren’t all useless after all.’ ”

Finding love, building a life

He hasn’t been hospitalized since he met a Franciscan Sister of Penance and Christian Charity in 1976 at a meeting of Charismatic Catholics at Ohio University.

“I thought he seemed awkward and uncomfortable, so I went up to say hello,” Penny Frese recalled. A close friendship developed, but he was slippery about his background, she said. Then one afternoon, during a walk in the woods, he revealed his psychiatric history.

“Honest to God, I felt like I couldn’t breathe,” she said. “I’d just walked an hour into the woods with a man who’s insane. I asked, ‘Are you violent?’ ”

She researched schizophrenia, and found that the best predictor of recovery, according to one source, “is a long-term loving relationship.” And she took that to include a close friendship. But she soon realized she couldn’t envision life without Frese. “I went to him and said, ‘I was thinking of marrying you, and he said, ‘I’ve been thinking that, too.’ And he proposed.”

She left the convent, but before their wedding day, he had a psychotic break and insisted they stay in a hotel three days to evade “people” looking for him. “I thought, ‘OK, I can handle this,’ ” she said. Marrying him, she said, was a leap of faith she never regretted. “I was so in love with him and still am.”

They have four grown children, and each has a 10 percent chance of developing schizophrenia. Typical onset is late teens to early 20s for males, and as much as 10 years later for females. The Freses don’t worry about the odds.

“What if John Nash hadn’t been born?” Penny Frese wondered.

Although her husband hasn’t been hospitalized since their marriage 31 years ago, he has short periods of two days when he lives on another plane, connecting ideas and concepts, finding extreme significance in certain words, and researching arcane interests until “it all fits in a grand scheme,” she said.

She sheltered the children from the episodes when they were small, said son Joe Frese, 29. “Mom would keep him in the bedroom and we weren’t allowed to talk to him,” he said. That changed after their father took his disease public. “Then he’d be dancing and singing in the kitchen,” JoeFrese said.

“It was fun,” Penny Frese said.

While the episodes don’t reach the level of the psychotic break he experienced in Milwaukee, Fred Frese said they can signal that his mind is going places it might have trouble leaving.

Munetz, of the Summit mental health board, can tell when Frese is entering an episode. “His thinking gets disorganized. It’s more grandiose than usual, or he starts wearing a hat.”

The hat is what Ray Gonzalez remembers from the late ’70s when he and Frese were colleagues at the mental hospital. Executive director of Planned Lifetime Assistance Network of Northeastern Ohio, a social service agency for people with mental illness, Gonzalez said Frese would slouch in the corner at staff meetings, a wool hat pulled down on his head.

“I didn’t know he was ill,” he said.

The only thing that separates Frese from the homeless people with schizophrenia is medication. “They don’t take their meds because they don’t think they’re sick,” Frese said.

And he knows for sure that he is. He’d like you to pass it on.

(Fred and I both appeared on the program: Minds On The Edge, where he shocked viewers and panel members by playing the role of someone with schizophrenia who didn’t believe they were ill and needed help.)